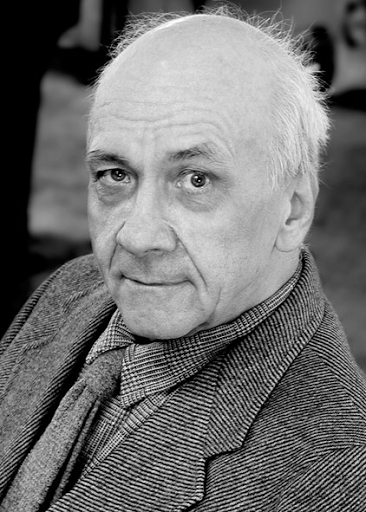

Composer Harold Boatrite dies at 89: “He thought long and hard about every note he committed to paper…”

Tuesday, May 18th, 2021We don’t live in an age that honors the dead much. Obituaries have all but disappeared from newspapers except for the most famous (not the most laudable, the most famous) and various homemade operations have sprung up to fill the gap, allowing do-it-yourself memorials from the bereaved on commercial websites … which isn’t the same.

Moreover obituaries are often late, published long after the bereaved are past the first shock of grief. So with composer Howard Boatrite (we wrote about him here), who died on April 26 at age 89. His close friend and collaborator, the former Philadelphia Inquirer book editor Frank Wilson, wrote about him over at his blog Books Inq:

John Donne famously wrote that “any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind.” But there are degrees of involvement. If you have known someone, as I knew Harold, for half a century, the sense of diminishment takes some dealing with.

Harold was born on April 2, 1932 and grew up in the Germantown section of Philadelphia. He was a friend of my late first wife, Zelda. They went to Germantown High together and both attended St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. If memory serves, Zelda took me to meet him sometime during the Christmas season in 1969.

I had heard his music, but was not terribly familiar with it at the time. What drew us together was our mutual familiarity with the school of philosophy known as scholasticism. I’d visit him at the house on Waverly Street in Center City that he shared with harpsichordist Temple Painter and he would visit us in our house in Germantown. Zelda’s daughter Gwen studied piano and theory with him.

Harold was largely self-taught, but he did study with Stanley Hollingsworth. I’m guessing that was when he was living in Detroit and driving a truck, having dropped out of Wayne State University. Sometime later he was awarded a fellowship to the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition with Lukas Foss and attended Aaron Copland’s orchestration seminars.

In 1961, pianist Rudolf Serkin invited him to be composer-in-residence at the Marlboro Music Festival. In 1967, he was given a doctor of music degree by Combs College of Music, and shortly thereafter he was appointed to the faculty of Haverford College, where he would teach theory and composition until 1980. From 1974 to 1977 he served on the music panel of the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and in 1982, to mark his 50th birthday, the Pennsylvania Alliance for American Music presented series of concerts devoted to his music. His music seems also to have been featured often at the Prague Autumn International Music Festival. Conductor Marc Mostovoy, when I emailed him about Harold’s passing, wrote back:

I was introduced to Harold’s music by Temple Painter, who was engaged as Concerto Soloists’ harpsichordist when I began the orchestra back in the 1960s. Over the years, Concerto Soloists (now the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia) performed eight of Harold’s orchestral works, premiering at least five, and playing a number of them many times.

I was immediately attracted to Harold’s music: tonal, yet contemporary; intellectual, yet moving. He thought long and hard about every note he committed to paper, constantly striving for the best possible solution. As a consequence, his output is relatively small, but the quality very high.

He served for many years as new music consultant to Concerto Soloists, helping select works the Orchestra would program each season – advocating for music well-crafted, and that the public could appreciate.

He was an excellent teacher as well. Concerto Soloists performed numerous works of his students to whom he passed on the mantra of quality over quantity. He espoused the importance of learning from great composers of the past, especially J.S. Bach, and writing music that was beautiful. I consider him an extremely important Philadelphia composer and teacher of our time.

… I saw Jeri Lynne Johnson conduct Harold’s music a number of times. I don’t know how much time she spent with Harold, but her conducting of his music gives the impression that she knew him very well. To paraphrase Whitman: Who hears these notes touches a man. (I must add that Marc Mostovoy has the same uncanny skill, though his Harold is one seen from a different, but equally authentic, angle.) Again, to paraphrase Whitman, Harold was large. He contained multitudes.

Postscript: The Philadelphia Inquirer obituary was published on June 2, here.

It’s a short review (under 800 words), so I won’t excerpt too much. You can read the whole thing, after all, right

It’s a short review (under 800 words), so I won’t excerpt too much. You can read the whole thing, after all, right