Playwright Matthew Gasda: “We are all Girardians now—whether we know it or not.”

Tuesday, July 30th, 2024

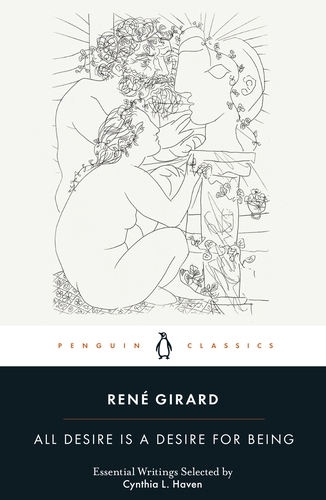

Interest in René Girard from an unexpected source: the current issue of Air Mail, which describes itself as a “mobile-first digital weekly that unfolds like the better weekend editions of your favorite newspapers.” Dramatist, novelist, and poet Matthew Gasda writes: “We are all Girardians now—whether we know it or not. The concepts minted in the early 1960s by the late French literary critic and philosopher René Girard explain the pathologies of the smartphone age as elegantly as Freud’s explained bourgeois neuroses at the turn of the last century.”

Gaspa is a voice worth listening to. Two years ago, the New York Times noted: “Matthew Gasda spent years writing plays on his electric typewriter, and almost no one seemed to care. With Dimes Square, his depiction of a downtown crowd, he has an underground hit.” And so he’s been a voice worth listening to ever since.

Which is especially good for All Desire is a Desire for Being, just out with Penguin Classics U.S. (The U.K. edition was published last year.) You can buy the book here. Meanwhile, read Gasda’s review of the book.

He continues: “While Freud was renowned in his own time, Girard, who died in 2015, is still far from a household name. A distinguished scholar and the author of nearly 30 books, he never broke through to a mass audience like his contemporary Harold Bloom, who transitioned from high theory to cultural critiques in the 1990s. Girard was not a public intellectual; he was a quietly influential, if recondite, academic: the Velvet Underground, not the Beatles.”

“Just as you don’t need to be a Marxist or a Freudian to find class struggle or the Oedipus complex useful, you do not need to be a Girardian, or a Catholic, to find Girard useful. Girard’s dogged attention to what he calls, echoing Nietzsche, the ‘eternal return’ of the scapegoat mechanism (the cruelty and stupidity of the mob) deserves our attention. Girard warns us, with moving pathos, that we are always on the verge of reprising the horrors of history; we are still prone, especially in times of crisis and change, to retribution and revenge (digital or physical).”

He continues: “All Desire Is a Desire for Being is not a reissue but a new collection of essential essays and aphorisms selected by [Cynthia] Haven. It’s the ideal way to read Girard, who only ever had one big idea. He was the kind of thinker Isaiah Berlin would have called a hedgehog, not a fox. But what an idea. Mimetic rivalry is a profound and disturbing discovery, and Girard dedicated his long and distinguished career to its explication. If he is right, we have to question whether the world we are actively creating—or perhaps passively re-creating—is not very, very wrong.”

Read the whole thing here. The bad news: it’s behind a sort of a paywall. The good news: all you have to do is include your email address at the bottom of the page to get access. Enjoy.