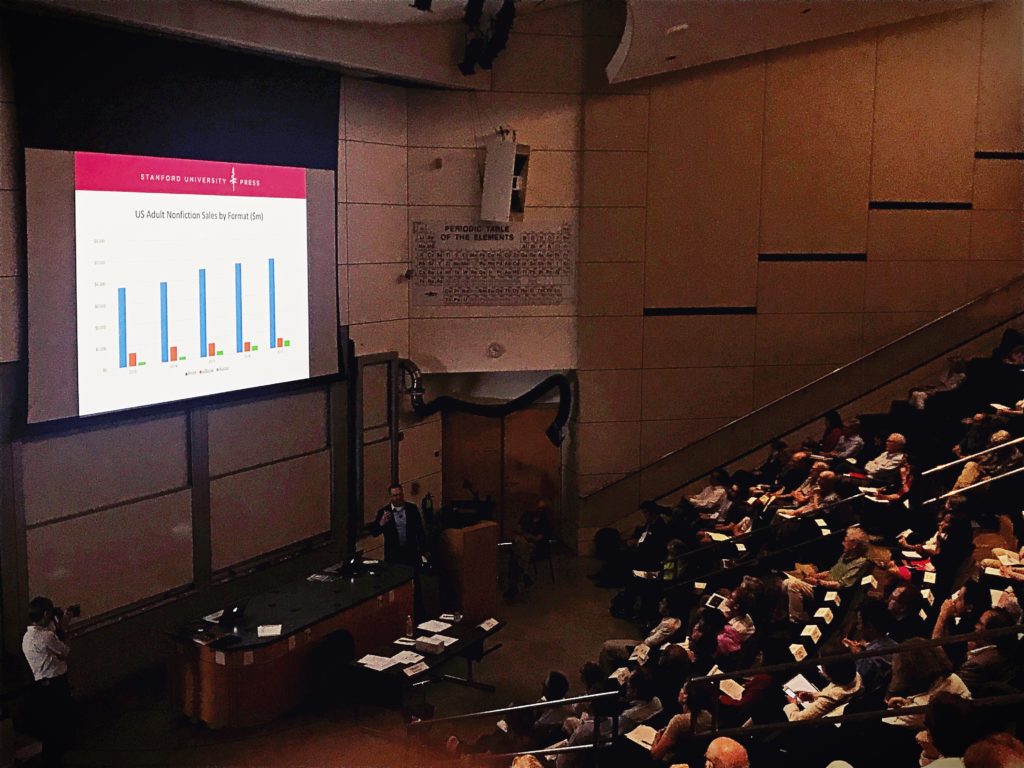

More than 200 people attended yesterday’s Faculty Senate meeting. (All photos by Ge Wang)

Passions ran high and emotions were raw at yesterday’s Stanford Faculty Senate meeting, which had to be moved to a larger venue to accommodate the crowd. One faculty said that the fury around this issue was unlike anything he’d seen at Stanford in more than a decade.

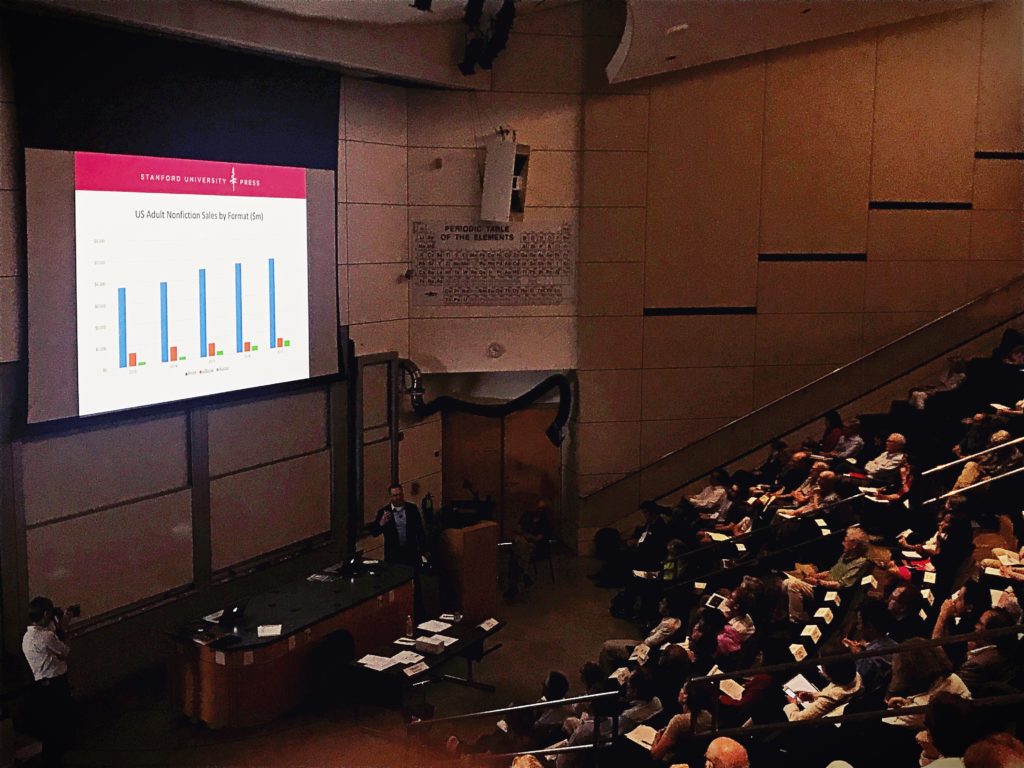

A recap: The university decided to terminate its support of Stanford University Press, which had been given $1.7 million supplements for several years. The amount, as many pointed out at the meeting, is chump change, about .027% of Stanford’s annual operating budget. The move, seeking to make the press “sustainable,” spurred national and international outcry and letters from thirteen Stanford departments, schools, and programs and sixteen letters from national and international learned societies, as well as extensive press coverage (including The Chronicle of Higher Education here). The controversy has been discussed on the Book Haven here and here and here.

In her brief remarks, Provost Persis Drell, claimed that the way her earlier comments had been interpreted was “totally contrary to my intent” and was “truly, deeply regrettable.” She said that she had held “no intention of closing the press.” She said the use of the word “sustainable” was not meant to be a synonym for “profit-making,” but added that the Press had to move “beyond one-year extensions” to its budget.

In her brief remarks, Provost Persis Drell, claimed that the way her earlier comments had been interpreted was “totally contrary to my intent” and was “truly, deeply regrettable.” She said that she had held “no intention of closing the press.” She said the use of the word “sustainable” was not meant to be a synonym for “profit-making,” but added that the Press had to move “beyond one-year extensions” to its budget.

Thomas Mullaney, professor of Chinese history, who had spoken on KQED about the future of the press, disagreed sharply: “Although some have since tried to downplay or deny the record on this point, it is established fact that dismissive, insulting, and unfounded statements were made about SUP by our administration – not just once, but repeatedly – and that these statements, when coupled with Stanford’s rejection of Stanford University Press’ budgetary request – set off a chain reaction of criticism of the Stanford administration and support for SUP, in equal measure.”

“I’ve never witnessed this kind of anger and resentment,” he said, recalling “meetings small and large wherein hands have slammed tabletops, voices have been raised, and in some cases, tears have clearly been held back. And of course, the tone of criticism only gets louder and sharper as one listens to the broader scholarly community across the rest of the United States and the world. Truly, this has been such a self-inflicted wound for Stanford, such an unforced error, that the situation feels largely out of control. It has been remarked that this PR debacle has probably already cost Stanford more money than it would have cost to endow SUP in perpetuity, let alone agreeing to the more modest 5-year package.”

Stanford Prof. David Palumbo-Liu asked Stanford University Press Director Alan Harvey point blank what would have happened without the resistance, what would have happened if the $1.7 million shortfall in their budget had, in fact, gone down as planned.

“I would have had to lay off half my staff,” Harvey replied in a beat. In turn, that move would have reduced the number of books the press could produce, which would have triggered more layoffs, he said. In short, a death spiral.

The negative impact are already evident in the current atmosphere of uncertainty, he said, with “hesitation on the part of scholars to submit books” for consideration to Stanford University Press. “The number of proposals has gone down,” and he characterized the pool of potential authors as “nervous.” When the university administration is conveying “a message of a lack of faith, people are going to hold off.”

The negative impact are already evident in the current atmosphere of uncertainty, he said, with “hesitation on the part of scholars to submit books” for consideration to Stanford University Press. “The number of proposals has gone down,” and he characterized the pool of potential authors as “nervous.” When the university administration is conveying “a message of a lack of faith, people are going to hold off.”

There was much talk about finding a solution to this intractable problem, but the answer seemed pretty obvious. Harvey stated it upfront: “An endowment is the only thing for a long-term sustainable press.” An endowment is the foundation of other major university presses – Harvard University Press, among others, has a large one. To date, the university has not permitted the press to do its own fundraising.

Comments were poignant and sometimes fiery. Notable among them, graduate student Jason Beckman referred to the stress caused by the decision to axe Press funding to support a few graduate scholarships instead: “Do not threaten to impoverish our futures while making overtures of support for our mental health. We see the repeated attempts by the provost and deans to weigh funding for graduate students against funding for the press and categorically reject this logic as a false choice. Make no mistake that we stand firmly with our faculty advisors and the press on this issue, and will not be used as rhetorical human shields for the administration’s myopic stance towards the Press and academic publishing. If this university did in fact value our mental health and well-being, it would consult us in good faith as actual stakeholders on major issues that may profoundly affect the academic fields in which we hope to establish careers.”

He referred to meeting some graduate students had with Provost Drell on May 2, about how to interpret the standing of the humanities and social sciences at Stanford in the wake of her decision to effectively defund the press. He said she discussed on the two types of degrees that she believes will serve our society going forward. “First, social science degrees buttressed by data proficiency and computer science skills, and second, humanities degrees, which are the ‘best equipped’ to deal with post-human concerns in a world of proliferating robotics and artificial intelligence. Far from assuaging our concerns, such a response only reaffirmed that this institution does indeed marginalize the humanities and social sciences—which seem to have value only insofar as they support STEM fields. A university that stands behind and supports all of its scholars and students, and that values scholarship itself, should not position itself as openly hostile or indifferent to certain kinds of scholarship. We find that bias clearly manifest in the Provost’s initial decision to decline the budget request from SUP, a decision that would devastate the press. ” (His comments are included in full on the “Save Stanford University Press” website here.)

The meeting ended by approving a resolution, along with an additional faculty committee that proponents argued will provide additional transparency and an invigorated role for faculty governance in matters pertaining to the Press.

And below: a few samplings from the promised Twitterstorm:

It’s not exactly haiku, but Twitter is kind of a cyberspace equivalent. Stanford inventor Ge Wang (we’ve written about him here and here), has gone to see the new film of Andrew Lloyd Weber‘s Cats (based on T.S. Eliot‘s poems) so we won’t have to. His review in 11 tweets is more nuanced than you might expect, however. He says the experience is … well, rather like a cat.

It’s not exactly haiku, but Twitter is kind of a cyberspace equivalent. Stanford inventor Ge Wang (we’ve written about him here and here), has gone to see the new film of Andrew Lloyd Weber‘s Cats (based on T.S. Eliot‘s poems) so we won’t have to. His review in 11 tweets is more nuanced than you might expect, however. He says the experience is … well, rather like a cat.