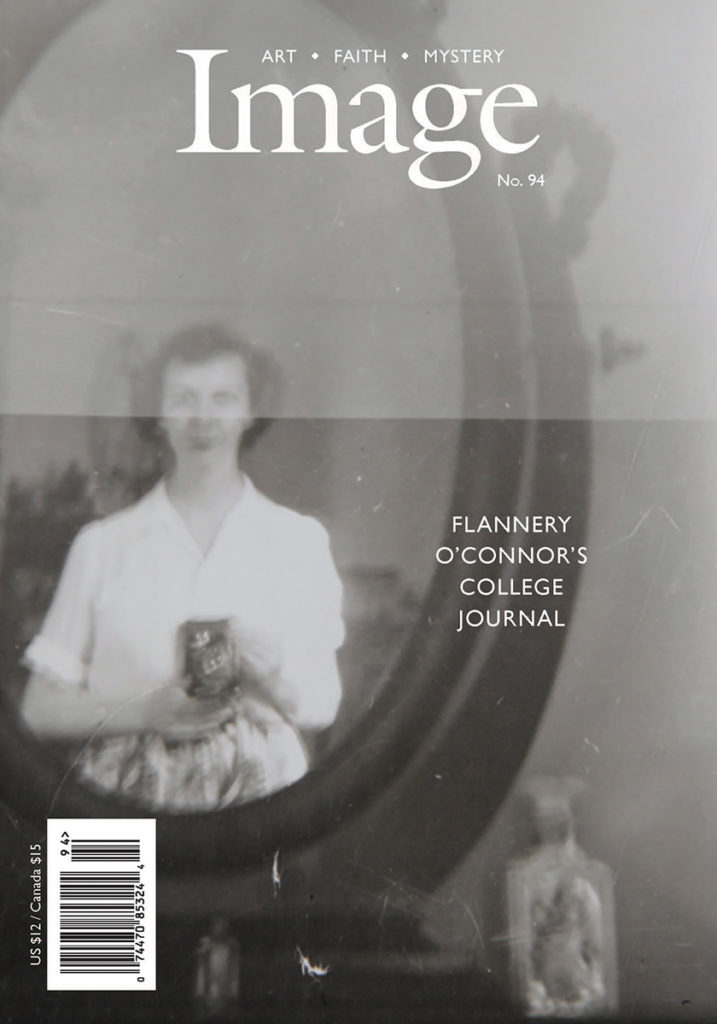

The teenage Flannery O’Connor: “I have so much to do that it scares me.”

Wednesday, November 29th, 2017

Flannery O’Connor with Robie Macauley and Arthur Koestler in Iowa, 1947. (Photo: Cmacauley/Creative Commons)

Image, a journal headed by the estimable Gregory Wolfe, has a scoop in its fall issue: the never-before-published college journal kept by writer Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964). According to Mark Bosco: “Four years ago my colleague Elizabeth Coffman and I embarked on a feature-length documentary about O’Connor’s life and work, and so we found ourselves at Emory University, where O’Connor’s archive had recently found a home. We already had over thirty hours of recorded interviews … It was time to see – and to touch – the physical objects of her life and photograph them for use in our documentary. We found in a box a Sterling notebook, standard issue for students in those days, inscribed ‘Higher Mathematics I.’ On perusing it we discovered an earlier attempt at a journal when O’Connor was just eighteen years old and already at Georgia State College for Women. She wrote her first dated entry during her Christmas Break, on December 29, 1943, and her last is marked February 6, 1944 – in all, a mere thirty pages. Reading it, you see O’Connor trying out the journal form as a way to examine her thoughts.”

It’s not online, so here is a short excerpt from “Higher Mathematics: An Introduction.” (And you can get a copy of the issue here.)

From the January 19, 1944 page in the journal:

From the January 19, 1944 page in the journal:

I begin to wonder – what next? I have always wondered, but this wondering is different. This wondering sees me on the threshold of something or near it. I realize for the first time that all these knots must be untied – all this tangle unstrung – and me got out of the middle of it.”

I don’t like to write about things that make me lonesome. Yet they are so big – to me now. I hate to think of saying “goodbye” – the actual mechanics of the thing grieve me more than the loss. The way the rest will do – what they may say. If I should begin to feel sorry for myself – however erroneously – I could easily move myself to a liquid-eyed condition, and that would be disastrous. I have such an affection for myself. It is second only to the one I have for Regina [her mother]. No one else approaches it. I realize that joyfully just now. If I loved anyone as much or more than myself and he were to leave, I would be too unhappy to want myself to advance; as it is, I look forward to many profitable hours. I have so much to do that it scares me.

She was already beginning to experience the symptoms of lupus, which she mistook for arthritis. She was diagnosed with the disease, which had killed her father, in 1952, and lived for another dozen years – five more than expected. She died at 39.

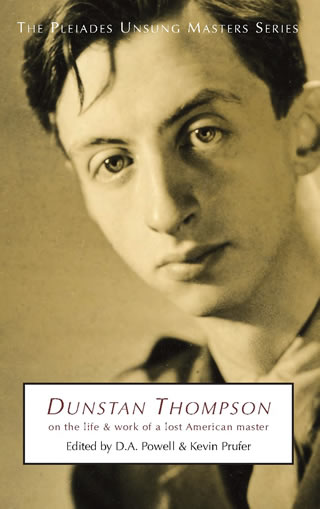

Here at last is

Here at last is  It’s one of the last poems in the volume. In keeping with the season, here’s Thompson’s short “Fragment for Christmas,” another poem from the very late Thompson:

It’s one of the last poems in the volume. In keeping with the season, here’s Thompson’s short “Fragment for Christmas,” another poem from the very late Thompson: Poet

Poet