"He assumed good and humanity in everyone."

My friend Jane Leftwich Curry organized an evening at Santa Clara University, where she is a professor of political science, to honor the playwright, dissident, and first president of the Czech Republic (and last president of Czechoslovakia), Václav Havel, who died in December.

The Wednesday event served as my introduction to Havel’s plays as well as to the university itself – despite its proximity, I had never seen SCU, which has the old Santa Clara Mission at its heart.

During the evening, a few of the university’s alumni performed staged readings from 1965’s The Memorandum and the much later 2007 Leaving.

The first was distinctly edgier – at least in the excerpted version. A deputy manager introduces a new “official” made-up language in the office, “Ptydepe.” Of course it’s all part of a bureaucratic coup d’état, and the managing director finds himself being edged out. In the second, a chancellor is leaving office – but does he have to leave the state villa, which has been his extended family’s home for years? The play was made into a movie in 2010, marking Havel’s debut as a director.

“We, here in Silicon Valley, do not live in an authoritarian society,” said Janey, who is author of six books on the politics of Central and Eastern Europe. “But we have much to learn from this man who had spent his years as a dissident and a writer and overnight took over as president not because he wanted power but because, as he said, ‘You cannot spend your whole life criticizing something and then, when you have a chance to do it better, refuse to go near it.'”

She gave a few examples of his ingenuity from his life as a dissident:

“He was creative not only in outsmarting the police when he could but also in living his life well in spite of all the pressures on him. There are thousands of stories of this … one that comes to mind here in this setting, is that, when he was in prison with the Archbishop of Prague, he organized chess tournaments – not, as the archbishop said at his state funeral, because Havel really liked chess, but because it provided a cover for Archbishop Duka to say mass under the ruse that the prisoners were just playing chess.

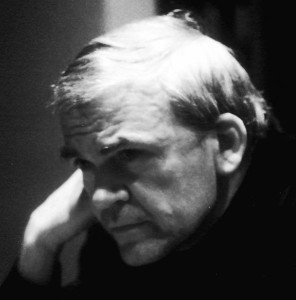

Author Curry

“Havel also laughingly told a s story of skiing up the high Tatra mountains – a struggle as he was both a heavy smoker and a non-athlete. He did it so he could meet at the top, on the border, with Polish dissidents like Jacek Kuron and Adam Michnik – neither of whom were any better skiers or athletes than he was and both of whom could match him as smokers. They came to share ideas and enjoy each other in the only place they could, a ski hut smack on the border of their two nations at the top of the Tatra mountains.” It was a good gamble – “the Czech and Polish secret police were too lazy to ski up the mountains to catch dissidents.”

When he was sworn in as president to replace the man who had imprisoned him, some asked what he would say to departing president Gustáv Husák at the cocktail party that followed the ceremony. “He thought about it and said he supposed they could talk about prison conditions as they had both served time in the same prison – Husak during World War II for being a communist, and he, under communism, for being a dissident. And so they did.”

The incident also illustrated a big theme in Havel’s life and leadership: inclusion, even extending to those who had harmed him. “He assumed good and humanity in everyone, even though most Czechs and Slovaks kept silent rather than lose their peaceful lives.”

The incident also illustrated a big theme in Havel’s life and leadership: inclusion, even extending to those who had harmed him. “He assumed good and humanity in everyone, even though most Czechs and Slovaks kept silent rather than lose their peaceful lives.”

After the fall of communism, when questions arose about the controversial policies of “lustration,” a government process to reintegrate former Communist into post-communist public life, “he reminded the nation that each and every one of them, himself included, had been part of making the communist system work. That the fault was shared by all and that each person had to account to himself for what he had done or not done. For Havel, then, the ultimate power was the power of the powerless.”

Steven Boyd Saum, editor of Santa Clara Magazine, also spoke – Saum is also attaché to the Honorary Consul General of the Czech Republic in San Francisco/Silicon Valley.

Saum hailed Havel as a man of “compassion and conscience.” He was “a bourgeois child” who, when denied a higher education under communism, became a lab assistant, a soldier, and a stagehand. “Havel, the man, was a hero.” Arthur Miller called him “the first surrealist president.”

Saum compared him to Thomas Jefferson, in his understanding that loyalties work best when they are to neighbors and communities, rather than monolithic states.

Nice venue

Change occurred so fast in Czechoslovokia that dissidents like Havel quickly found themselves catapulted to power. The skills of a dissident didn’t always translate into the skills of a politician. Havel believed firmly that when you change the system, people will change. He had respect even for the people who had betrayed him and his colleagues, or who had been silent during their persecution – “he stuck up for them.”

His first biographer Eda Kriseova wrote rather a hagiography. “The world needs heroes,” she said. “I am giving you one.”

(Another biographer, John Keane, author of Václav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts, answers questions here.)