The battle for Arthur Miller’s papers: and the winner is … no surprise.

Wednesday, January 10th, 2018

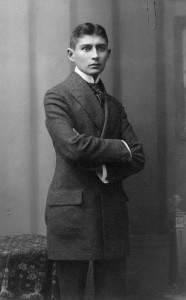

Arthur Miller, University of Michigan grad, in 1939

When I saw a New York Times headline about the acquisition of the Arthur Miller papers, I hoped it would have something to do with our common alma mater. But it looks like the University of Michigan was long ago priced out of the market for its most glorious literary alum:

More than 160 boxes of his manuscripts and other papers have been on deposit for decades at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, uncataloged and all but inaccessible to scholars, pending a formal sale. Another cache — including some 8,000 pages of private journals — remained at his home in rural Connecticut, unexplored by anyone outside the intimate Miller circle.

Now, the Ransom Center has bought the entire archive for $2.7 million, following a discreet tug-of-war with the Miller estate, which tried to place the papers at Yale University despite the playwright’s apparent wishes that they rest in Texas.

That battle pitted two of the nation’s most prestigious, and deep-pocketed, archival institutions against each other, in a mini-drama mixing Milleresque high principle with more bare-knuckled competition. And it cracks a window onto the rarefied trade in writers’ papers, and the delicate calibrations of money, emotion and concern for posterity that determine where they ultimately come to rest.

Miller opted for the Ransom Center years ago, when it was positioning itself as one of the most aggressive players in the increasingly aggressive archival world. (Oil dollars are behind its quick climb to the top). The author and playwright was hard up for cash and looking for a tax break.

The archive includes everything from the development of Death of a Salesman and The Crucible to Miller’s confrontation with the House Un-American Activities Committee. It also includes his advocacy against censorship from his last years before his death in 2005.

But what everyone wants to know: are there more hot letters to his second wife, Marilyn Monroe? Unlikely, but something better: his unfinished essay, which he started on the day of her funeral on Aug. 8, 1962. It was frequently revised, but never published, and from the snippet view on the New York Times page, it was very, very bitter. “Instead of jetting to the funeral to get my picture taken I decided to stay home and let the public mourners finish the mockery,” Miller wrote. “Not that everyone there will be false, but enough. Most of them there destroyed her, ladies and gentleman.”

Read the whole thing here.

Postscript on 1/12: Our favorite archivist (and also friend) Elena Danielson, former director of the Hoover Library & Archives (and author of The Ethical Archivist), favors us with a reaction once again:

Thank you, Elena!

Whenever these million dollar deals are announced in the press, ordinary donors start to get grand ideas about the financial value of their papers and it takes a while for the asking price to come down to earth. The tax break referred to in the article is the result of Nixon’s huge tax break for donating his own papers. In response the law was changed, you cannot get the tax break for donating your own papers, however your heirs on the other hand can claim the deduction. Determining the market value of a collection is an imprecise science.

The auction value and the research value are usually two very different things. Auction value depends primarily on name recognition. In this case, however, the collection has both artifactual and research value, so the price tag should probably be high. And keeping a collection together, all in the same place, retaining its integrity, is a basic ethical principle. The Arthur Miller papers are a national treasure, so the main thing is to keep it in the U.S. in a well funded, well run archival repository, which the Ransom Center fortunately is.

And then at the age of 18 I picked up a book called The Hidden Ireland by a writer I had never heard of, Daniel Corkery. It had been published in 1925. The book follows the shattered narrative of the Cromwellian clearances in Ireland in the 18th century. It alights in their aftermath in a small part of Gaelic Munster, which is called Slieve Luachra, a mountainous area on the Cork Kerry border. Corkery writes about poets such as Aodhagán Ó Rathaille and Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin. He records that they spoke the Irish language and wrote their poetry in it. That they were witnesses to the destruction of that language and the breaking apart of the Bardic order. “What Pindar is to Greece, what Burns is to Scotland … that and much more is Eoghan Ruadh to Ireland,” wrote Corkery.

And then at the age of 18 I picked up a book called The Hidden Ireland by a writer I had never heard of, Daniel Corkery. It had been published in 1925. The book follows the shattered narrative of the Cromwellian clearances in Ireland in the 18th century. It alights in their aftermath in a small part of Gaelic Munster, which is called Slieve Luachra, a mountainous area on the Cork Kerry border. Corkery writes about poets such as Aodhagán Ó Rathaille and Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin. He records that they spoke the Irish language and wrote their poetry in it. That they were witnesses to the destruction of that language and the breaking apart of the Bardic order. “What Pindar is to Greece, what Burns is to Scotland … that and much more is Eoghan Ruadh to Ireland,” wrote Corkery.