No love lost: “authors are some mean mofos”

Saturday, July 2nd, 2011A few weeks ago, we wrote a few words on famous feuds between authors.

What better way to follow up than with nasty letters authors wrote on each others’ work? I read flavorwire’s post on the topic some time ago, which excerpted a longer column from The Examiner here, with a Part 2 here. It seems like as a good a way as any to begin the holiday weekend.

Take this one:

Wyndham Lewis on Gertrude Stein: “Gertrude Stein’s prose-song is a cold black suet-pudding. We can represent it as a cold suet-roll of fabulously reptilian length. Cut it at any point, it is the same thing: the same heavy, sticky, opaque mass all through and all along.”

As one commenter, Dave, concluded: “Authors are some mean mofos.”

Instead of resnipping the earlier lists, however, I decided to raid the suggestions from readers.

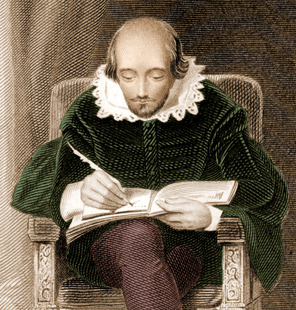

Ben Jonson on Shakespeare: “I remember the players have often mentioned it as an honor to Shakespeare that in his writing, whatever he penned, he never blotted out a line. My answer hath been, ‘Would he had blotted a thousand.”

Baudelaire on Voltaire: “I grow bored in France – and the main reason is that everybody here resembles Voltaire … the king of nincompoops, the prince of the superficial, the anti-artist, the spokesman of janitresses, the Father Gigone of the editors of Siècle.”

H.G. Wells on Henry James: “A hippopotamus trying to pick up a pea.”

Louis-Ferdinand Céline on D.H.Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover: “600 hundred pages for a gamekeeper’s dick, it’s way too long.”

As far as potty-mouth goes, try this one: Stephen Fry on Dan Brown‘s The DaVinci Code: “Complete loose stool water. Arse gravy of the very worst kind.”

William Hazlitt about his good friend Coleridge: “Everlasting inconsequentiality marks all he does.”

Then there’s a Jane Austen pile-on:

Mark Twain: “Just the omission of Jane Austen’s books alone would make a fairly good library out of a library that hadn’t a book in it.”

Charlotte Bronte‘s criticism is less snarky, more an excellent Romantic era critique of the preceding era’s Classicism:

“. . . anything energetic, poignant, heartfelt, is utterly out of place in commending these works; all such demonstration the authoress would have met with a well-bred sneer . . . She does her business of delineating the surface of the lives of genteel English people curiously well; there is a Chinese fidelity, a miniature delicacy in the painting: she ruffles her reader by nothing vehement, disturbs him by nothing profound: the Passions are perfectly unknown to her; she rejects even a speaking acquaintance with that stormy Sisterhood; even to the Feelings she vouchsafes no more than an occasional graceful but distant recognition; too frequent converse with them would ruffle the smooth elegance of her progress. Her business is not half so much with the human heart as with the human eyes, mouth, hands, and feet; what sees keenly, speaks aptly, moves flexibly, it suits her to study, but what throbs is the unseen seat of Life and the sentient target of death–this Miss Austen ignores, she no more, with her mind’s eye, beholds the heart of her race than each man with bodily vision, sees the heart in his heaving breast. Jane Austen was a complete and most sensible lady, but a very incomplete, and rather insensible (not senseless) woman . . .”

Ceallaig‘s perceptive comment from an intelligent heart: “My question is: if Mark Twain hated Jane Austen why does he say ‘every time I read it?’ Wouldn’t once have been enough? Ditto Noel Coward‘s slam on Oscar Wilde: ‘Am reading more of …’? as if the first dose wasn’t sufficient? I’m sure most of these slams were meant to be witty, and I agree with a number of them, but … wit used for the sake of nasty doesn’t work for me.”

Then I found this interesting post, from bibliokept. David Foster Wallace on Bret Easton Ellis. I leafed through Ellis’ Less Than Zero in the Stanford Bookstore a couple decades ago, and found it ugly and depraved. I haven’t read Wallace at all, and have been put-off by his super-celebrity status, which, morbidly, seemed to accelerate with his 2008 suicide – until I read this excerpt from an interview:

“I think it’s a kind of black cynicism about today’s world that Ellis and certain others depend on for their readership. Look, if the contemporary condition is hopelessly shitty, insipid, materialistic, emotionally retarded, sadomasochistic, and stupid, then I (or any writer) can get away with slapping together stories with characters who are stupid, vapid, emotionally retarded, which is easy, because these sorts of characters require no development. With descriptions that are simply lists of brand-name consumer products. Where stupid people say insipid stuff to each other.

‘If what’s always distinguished bad writing—flat characters, a narrative world that’s clichéd and not recognizably human, etc.—is also a description of today’s world, then bad writing becomes an ingenious mimesis of a bad world. If readers simply believe the world is stupid and shallow and mean, then Ellis can write a mean shallow stupid novel that becomes a mordant deadpan commentary on the badness of everything. Look man, we’d probably most of us agree that these are dark times, and stupid ones, but do we need fiction that does nothing but dramatize how dark and stupid everything is?

“In dark times, the definition of good art would seem to be art that locates and applies CPR to those elements of what’s human and magical that still live and glow despite the times’ darkness. Really good fiction could have as dark a worldview as it wished, but it’d find a way both to depict this world and to illuminate the possibilities for being alive and human in it. You can defend Psycho as being a sort of performative digest of late-eighties social problems, but it’s no more than that.”

I’d say it’s considerably less.

Bibliokept‘s thoughtful consideration of Ellis versus Wallace definitely worth a thoughtful read.