Remembering Michel Serres (1930-2019): on angels, messages, and television sets

Monday, June 3rd, 2019

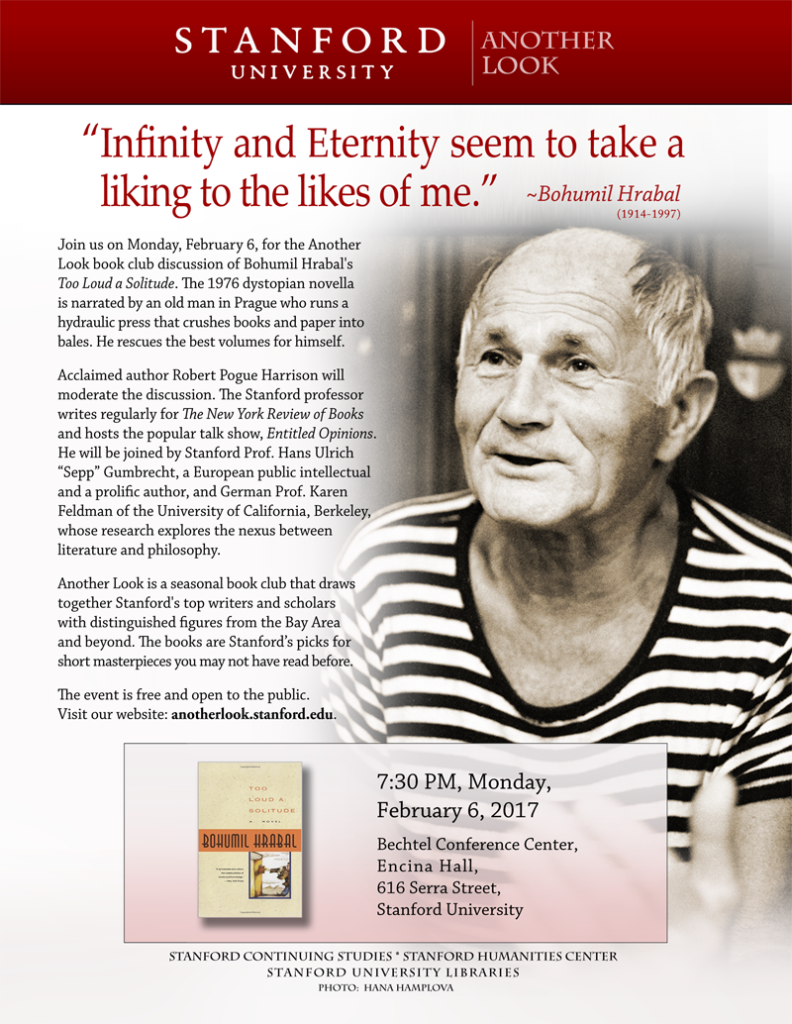

The tributes have started to pour in from every direction. “No one is ‘surprised’ by a death in the 89th year of life, even today. That his readers in many countries must have experienced the news of the death of Michel Serres on Saturday as a painful incision thus means – even if we, the successors and heirs, do not want to admit this – that an epoch of the spirit has come to an end is where one generation (not a ‘school’) of independent thinkers has responded to the challenges of the present – one last time from France and Europe for the world.” So wrote Stanford’s eloquent and eminent Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht in Die Welt over the weekend. That’s a rough translation. You can read “Der letzte Geistes-Gigant,“ (The last giant of the spirit”) in German here.

Dan Edelstein, chair of Stanford’s Division of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages, confessed to a “grande tristesse.” He continued: “I occasionally audited Michel’s classes when he still taught at Stanford. My favorite memory was when he stood up one day in mid-sentence, walked over to the white board, and wrote something in ancient Greek. Then he sat down, without bothering to comment on it. I’m not sure any of us could even read what he’d written, but it felt like we’d just witnessed the passing of an age.”

Derek Schilling, a former Stanford faculty member and now chair of the French Department at Johns Hopkins’ University, where Serres once taught, wrote this in a letter to Edelstein: “There were no thinkers of his generation fully comparable to Michel Serres, so original and idiosyncratic was his poetic approach to knowledge, and so firm his belief in the communicability of thought and in the exigencies of style. The breadth of Michel’s teachings, and the wisdom and openness to interdisciplinary inquiry that came along with them, were to mark generations of students and colleagues. Not all of them picked up a Gascon accent, though each would carry something of that particular music with them through the years.”

Another former Stanford faculty member, James Winchell, recalled meeting Serres long ago: “When I first arrived at Stanford in 1988, I had yet to ‘check in’ at the Dept. of French & Italian (semester had not begun) and not all colleagues were back on campus yet. So I was taking a long walk around the quad and in the eucalyptus groves and in the distance I saw a white-headed figure pedaling toward me on a bicycle. As he rode up his hair stood out à la Einstein and he pulled up and said without pause, ‘Vous êtes James?’ (We hadn’t met during my ‘job-candidate visit’ because he wasn’t on campus at that time.) I of course replied in the affirmative, and received the warmest welcome to my new faculty from one of my two most prestigious – and least pretentious – colleagues. Michel even visited my class on occasion, and would afterward comment on my whiteboard visuals.” (Photo at right commemorated the occasion.) His more formal Facebook tribute, in French and English:

Hommage à Michel Serres: Comme m’arrive à l’esprit de plus en plus de ces jours, je me rassure que les atomes, les sémences et les particules (y inclus ses paroles, ses pages, son corps, et les reflets du souvenir chez ses étudiants et ses amis), qu’il a distribués si généreusement pendant toute sa vie, se ramasseront dans une turbulence aussi cosmologique et bien branchée que celle qui la précède: Comme chez Lucrèce, De rerum natura.”

In English translation: “As occurs to me more and more often these days, I find reassurance that the atoms, seed-grains, and particles (including his words, his pages, his body and the reflections in the memories of his students and friends), which he sowed so generously throughout his life, will gather themselves into a turbulence as galactic and pluri-formed as the one preceding it: As in Lucretius’ On The Nature of Things.”

I commented over the weekend that I had interviewed him for the only English-language video he had made – but it’s apparently not the only English-language interview. One appeared online over the weekend. Hari Kunzru‘s Q&A was commissioned by Wired, but then never published, considering it “to French.” The interview at London’s Hazlitt hotel in Soho took place on January 10, 1995. James Flint made a third. “Serres kindly spoke in English and I have retained most of his quirky phrasing.” A few excerpts:

HK: Why are angels important for someone thinking about new media and communications?

MS: In my book about angels I try to put a short circuit between the very ancient tradition of angels in monotheistic or polytheistic traditions and the jobs now about messages, messenger and so on. I think that this connection, between ancient time and new time is very interesting to understand. On one hand, the ancient forms and ancient traditions, and on other hand, the new and the real jobs about medias. Because our job – your job – is to receive messages, to translate messages, and to send messages in some respect. Your work is about messages. You are a messenger. I am a messenger. I am a professor. You are a journalist. Our job is about messages.

HK: I’m interested in what you say about history. People conceptualise the present day as a time when there has been a rupture with the past. You are deliberately making a link between the two.

HK: I’m interested in what you say about history. People conceptualise the present day as a time when there has been a rupture with the past. You are deliberately making a link between the two.

MS: The problem is to think about the historic link between ancient time and the new world because this link is cut. Many people think about our time without reference to traditions. But if you read the amount of books about angelology in the Middle Ages, if you translate certain words into modern language you see that all the problems were about translation, about messages. These are exactly our problems. When you put a short circuit, you obtain sparkles and these sparkles give light to the traditions and our jobs.

HK: Part of the effect of using the trope of the angel to understand communication seems to me to invest our world, the modern world with a sense of the sacred. Would you agree with that? Maybe you would make a distinction between the sacred and the spiritual.

MS: Yes, the spiritual. My first point was to understand and to clarify our jobs in a practical way. But I avoid in certain the spiritual problems. I prefer to speak about logical problems or practical problems. The problem of good and evil for instance is very easy to explain when you see that the messenger or channel is neutral, and on a neutral channel you can say I love you or I hate you.

HK: The channel itself is neutral.

MS: Yes, and the problem is not spiritual. The problem is to explain why with the same channel, the same messenger, you can get bad or good results. You see?

HK: Perhaps. You’re saying your book is a book of ethics.

MS: In many ways, yes you are right.

HK: But you’re saying we should approach ethics not in terms of some a priori sense of the spiritual, but framed in terms of transmission and communication.

MS: Yes. I can give an example of ethics. I am a professor, and when I give a lecture, in the beginning I am Michel Serres, I am the real person who speaks. I must make a seduction for my students. I may begin with a joke, for example. After that I must disappear as a person on behalf of the message itself. The problem of disappearing as myself to give way to the message itself is the ethics of the messenger. Do you see what I mean?

HK: So you reduce your own subjectivity

MS: Yes, the reason why angels are invisible is because they are disappearing to let the message go through them.

***

MS: Exactly. If you read medieval angelology you find exactly the same demonstrations because all the problems for angelology – what is a message? who are the messengers? what is the messenger’s body? – like Saint Thomas Aquinas, the early church fathers, the Pseudo-Dionysius, and so on. In the beginning of my book I quote the problem of the sex of the angels. Everybody smiles about this problem, but it is a serious one, a problem about transmission.

MS: Exactly. If you read medieval angelology you find exactly the same demonstrations because all the problems for angelology – what is a message? who are the messengers? what is the messenger’s body? – like Saint Thomas Aquinas, the early church fathers, the Pseudo-Dionysius, and so on. In the beginning of my book I quote the problem of the sex of the angels. Everybody smiles about this problem, but it is a serious one, a problem about transmission.

HK: A serious functional problem.

MS: Exactly.

HK: This is what I began to find when I looked at scholastic philosophy. Having thought it was full of ridiculous problems about angels on pinheads I found that serious problems were simply framed in this vocabulary.

MS: You are right. I was very surprised to find that in the beginning of my career.

HK: Let’s talk about television. You return again and again to the negative things that TV brings us. I’m interested to know whether all media is a form of pollution, or whether its just the mass media, which makes the viewer or listener passive. I am interested in the possibility of two-way media, two-way means of communication, an interactive form. Do you think that would be less socially damaging than the mass media?

MS: In the beginning of our history many centuries ago, the Greek fabulist Aesop said that the tongue was the best and the worst thing in the world. This very ancient sentence is exactly the same for us. It is so for the tongue, for language, but also for very sophisticated channels of communication and for instance your question about the TV is a good question because TV is one of the best channels in the world to have information, to have education, to receive instruction, to have OpenUniversity, to have a good lecture, to discover the world. It is the best channel, but on the contrary, do you know that in the US now a typical teenager has seen 20000 murders already in his life, already at fourteen years old? It is the first time in history that we teach murder to children in this intensive way. It is the best channel and the worst at the same time, and it is not a discovery because Aesop told us this centuries ago. I think it is a paradox of communication. When all channel is neutral it can carry the best message and the worst.

***

JF: Ballard remarks that Britain and perhaps France because we have relatively few channels, we are more mediated than the US because there are so many channels and it’s on all the time like wallpaper.

MS: The increasing number of channels doesn’t really change the situation. whether you have ten or two hundred channels, they all say the same thing. The reality doesn’t change.

Read the whole thing here.

Postscript on 4 June from Maria Adle Besson, who directs the Ivy Plus European Leaders – The Forum of European Leaders in Paris (we’ve written about her here and here): An exceptional philosophical storyteller, an encyclopedist in love with life, curious of connections, odd or secret links between things. I had the chance to meet Michel Serres at Stanford when he became an ‘Immortal’ and attend a few of his eclectic lectures across the years. The last one was on the Bearded Men of the 19th Century, where he intertwined Marx with Monet, Darwin,Victor Hugo, Freud, Zola, Renoir… Disrupters of the age of inventions all had beards; we were left to draw our own conclusions. In France, I called him several times to organize an event around him; his responses often threw me off. ” I am in the middle of the vineyards, in my country, I can smell the …, I hear… ” ” What do you mean, ‘open’ the conference? How does one ‘open’ a conference?” While his head followed all evolutions, his feet stayed grounded in the past, nature, the land and the French language.

Postscript on 4 June from Maria Adle Besson, who directs the Ivy Plus European Leaders – The Forum of European Leaders in Paris (we’ve written about her here and here): An exceptional philosophical storyteller, an encyclopedist in love with life, curious of connections, odd or secret links between things. I had the chance to meet Michel Serres at Stanford when he became an ‘Immortal’ and attend a few of his eclectic lectures across the years. The last one was on the Bearded Men of the 19th Century, where he intertwined Marx with Monet, Darwin,Victor Hugo, Freud, Zola, Renoir… Disrupters of the age of inventions all had beards; we were left to draw our own conclusions. In France, I called him several times to organize an event around him; his responses often threw me off. ” I am in the middle of the vineyards, in my country, I can smell the …, I hear… ” ” What do you mean, ‘open’ the conference? How does one ‘open’ a conference?” While his head followed all evolutions, his feet stayed grounded in the past, nature, the land and the French language.

When I asked the University to invite him for a major event in Paris, insisting that he was a major figure in France, the answer was: “He does not have an email. We cannot invite him. Who has heard of someone without an email address?”

Sad that after René Girard, another great man in the humanities disappears from my inner intellectual and affective landscape.

On the other hand, it should be highlighted that from the very beginning of his engagement with the concept, and even in its translation as composure, Gelassenheit never meant to Sepp acceptance, resignation, in one word: quietude. Rather, I propose the following rendering of Sepp’s translation: composure implies a particularly active relationship with current events, in which the present is projected into a much wider chain of events, and going back and forth different historical periods is the trademark of Gelassenheit understood as composure – a trademark also of Erich Auerbach’s masterpiece, Mimesis.

On the other hand, it should be highlighted that from the very beginning of his engagement with the concept, and even in its translation as composure, Gelassenheit never meant to Sepp acceptance, resignation, in one word: quietude. Rather, I propose the following rendering of Sepp’s translation: composure implies a particularly active relationship with current events, in which the present is projected into a much wider chain of events, and going back and forth different historical periods is the trademark of Gelassenheit understood as composure – a trademark also of Erich Auerbach’s masterpiece, Mimesis. In the Q&A session, the three-time Olympic gold-medal swimmer Pablo Morales was asked what he missed the most of his life as a top athlete. Morales’s answer was in itself eventful. He did not exactly miss the exhaustive training routine, although the discipline required by it can be fully appreciated. Indeed, almost all top athletes have impose on their bodies such stress throughout their careers that the most common outcome is a series of injuries they have to endure their entire lives. Nor even gold medals and world records were what Morales missed the most; after all a top athlete is obsessed with improving her performance, therefore, any victory may be clouded by the seemingly inescapable question: could I have done it any better?

In the Q&A session, the three-time Olympic gold-medal swimmer Pablo Morales was asked what he missed the most of his life as a top athlete. Morales’s answer was in itself eventful. He did not exactly miss the exhaustive training routine, although the discipline required by it can be fully appreciated. Indeed, almost all top athletes have impose on their bodies such stress throughout their careers that the most common outcome is a series of injuries they have to endure their entire lives. Nor even gold medals and world records were what Morales missed the most; after all a top athlete is obsessed with improving her performance, therefore, any victory may be clouded by the seemingly inescapable question: could I have done it any better? After all, what is a seminar taught by Sepp if not an immersion in Gelassenheit? It is not the case with Sepp’s wrap-up of a panel – be it surprisingly good or merely mediocre? In both cases, while rendering more complex the ideas espoused by the speakers, Sepp is creating an environment where it becomes possible, almost at hand, to find themselves lost in focused intensity.

After all, what is a seminar taught by Sepp if not an immersion in Gelassenheit? It is not the case with Sepp’s wrap-up of a panel – be it surprisingly good or merely mediocre? In both cases, while rendering more complex the ideas espoused by the speakers, Sepp is creating an environment where it becomes possible, almost at hand, to find themselves lost in focused intensity. Second: Gelassenheit as serenity is the form of emergence, in the sense developed by Umberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, notion that along with autopoiesis were important in the unfolding of the theoretical framework of the materialities of communication paradigm.

Second: Gelassenheit as serenity is the form of emergence, in the sense developed by Umberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, notion that along with autopoiesis were important in the unfolding of the theoretical framework of the materialities of communication paradigm.

I suppose that what I mean is that Sepp is listened to by people who wouldn’t dream setting foot on conferences such as this one. And this raises the question: could Sepp be both one of us and one of them? Could this be a case of intellectual schizophrenia? I don’t think so. There are, to be sure, many connections between what Sepp does in class and what he does outside. He always remained and after all is the same person. However, the attempt to engage vast unknown audiences is something that after all defines his difference vis-à-vis most of us. It is a difference that many of us would quickly grant is a measure of Sepp’s trademark as an intellectual, both public and private, and intellectual for whom the private/public distinction does not obtain. In claiming that Sepp is an intellectual public and private I am thus claiming that he is unlike most of us. … This is very high compliment indeed.

I suppose that what I mean is that Sepp is listened to by people who wouldn’t dream setting foot on conferences such as this one. And this raises the question: could Sepp be both one of us and one of them? Could this be a case of intellectual schizophrenia? I don’t think so. There are, to be sure, many connections between what Sepp does in class and what he does outside. He always remained and after all is the same person. However, the attempt to engage vast unknown audiences is something that after all defines his difference vis-à-vis most of us. It is a difference that many of us would quickly grant is a measure of Sepp’s trademark as an intellectual, both public and private, and intellectual for whom the private/public distinction does not obtain. In claiming that Sepp is an intellectual public and private I am thus claiming that he is unlike most of us. … This is very high compliment indeed.