Is Longfellow’s translation of Dante the best?

Monday, March 28th, 2016I have a number of translations of Dante’s The Divine Comedy in my home – among them the translations of Charles Singleton, Dorothy L. Sayers, Peter Dale, and others.

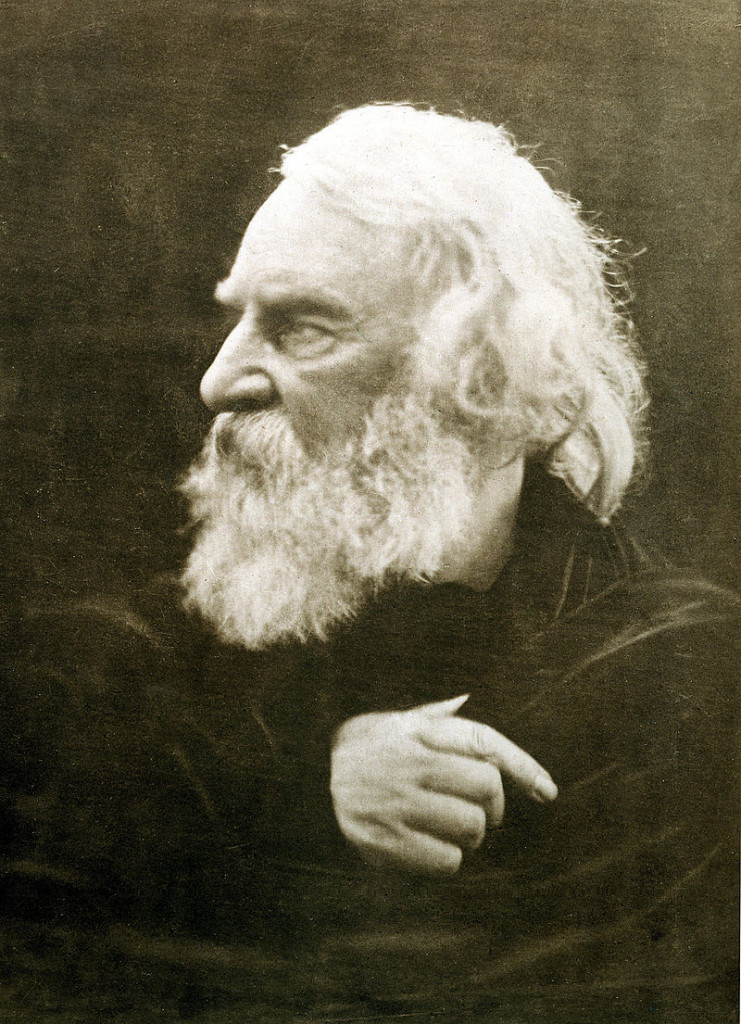

But perhaps the most neglected one is the battered volumes I found on ebay, translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. This overlooked translation finds a new champion in Joseph Luzzi, in “How to Read Dante in the 21st Century” in the online edition of The American Scholar:

From one poet and scholar…

… one of the few truly successful English translations comes from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a professor of Italian at Harvard and an acclaimed poet. He produced one of the first complete, and in many respects still the best, English translations of The Divine Comedy in 1867. It did not hurt that Longfellow had also experienced the kind of traumatic loss—the death of his young wife after her dress caught fire—that brought him closer to the melancholy spirit of Dante’s writing, shaped by the lacerating exile from his beloved Florence in 1302. Longfellow succeeded in capturing the original brilliance of Dante’s lines with a close, sometimes awkwardly literal translation that allows the Tuscan to shine through the English, as though this “foreign” veneer were merely a protective layer added over the still-visible source. The critic Walter Benjamin wrote that a great translation calls our attention to a work’s original language even when we don’t speak that foreign tongue. Such extreme faithfulness can make the language of the translation feel unnatural—as though the source were shaping the translation into its own alien image.

… to another.

Longfellow’s English indeed comes across as Italianate: in surrendering to the letter and spirit of Dante’s Tuscan, he loses the quirks and perks of his mother tongue. For example, he translates Dante’s beautifully compact Paradiso 2.7

L’acqua ch’io prendo già mai non si corse;

with an equally concise and evocative

The sea I sail has never yet been passed:

Emulating Dante’s talent for internal rhymes laced with hypnotic sonic patterns, Longfellow expertly repeats the s’s to give his line a sinuous, propulsive feel, which is exactly what Dante aims for in his line, as he gestures toward the originality and joy of embarking on the final leg of a divinely sanctioned journey. Thus, Longfellow demonstrates the scholarly chops necessary to convey Dante’s encyclopedic learning, and the poetic talent needed to reproduce the sound and spirit—the respiro, breath—of the original Tuscan.

Read the whole essay here – it’s fairly short and very interesting.