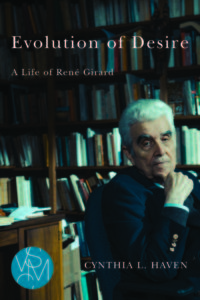

Johns Hopkins interviews me on “René Girard and the Mysterious Nature of Desire.”

Friday, August 10th, 2018

A little mysterious himself.

Bret McCabe makes a brief appearance in the pages of Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard. The humanities writer for Johns Hopkins University, where René Girard spent some of the most important years of his life, was interviewing JHU legendary Prof. Richard Macksey a few years ago. They had been discussing the renowned 1966 Baltimore conference, organized by Girard, Macksey, and Eugenio Donato, which brought French thought to America. Then Bret McCabe finds a Davidoff matchbox nestled among Macksey’s papers. As a madeleine famously recalls Proust to his past, so the matchbox stirs distant memories in Dick Macksey: “I haven’t had Davidoff since Jacques Derrida was here.”

Last spring, Bret did a Q&A with me for Johns Hopkins University about “René Girard and the Mysterious Nature of Desire.” It went up on the Johns Hopkins website this week. An excerpt:

While Evolution of Desire is written for a general reader, I imagine that general reader is probably going to have some interest in and familiarity with literary criticism. How would you describe Girard’s theory of mimetic desire for a layperson, and why it has such lasting significance?

I’d start this way: We want what others want. We want it because they want it. These desires are shaped by our restless imitation of others. When the coveted goods are scarce, these desires pit us against one another—on an individual level, on a community level, and on a global scale as well. It causes divorces and it causes international wars. It causes children to fight over a five-buck toy in the sandbox.

Legendary Dick Macksey at JHU

René Girard wrote: “All desire is a desire for being.” It’s a phrase I use often because this imitated desire is powered by the wish to be the person who models our desire for us. We think that this person possesses metaphysical qualities we do not. We imagine the idolized individual has the power, charisma, cool, wisdom, equanimity. So we want that person’s job, shirt, car, spouse. The relationship, as he wrote, is that of the relic to the saint.

The nature of desire is mysterious. René said: “Desire is not of this world. That is what Proust shows us at his best: it is in order to penetrate into another world that one desires, it is in order to be initiated into a radically foreign existence.” No wonder he was such a devotee of Proust!

Follow him on Twitter: @BretMcBret

That passage succinctly answers the second part of your question as well. Our most fundamental longings—throughout the centuries—are addressed in his corpus. That is why it is important, and always will be important.

The final question from Bret:

Finally, I know it’s a bit of folly to ask such things, but as you point out in both your introduction and postscript, Girard is actually somebody who might have something to tell us about right now. He died in 2015, prior to the elections in 2016 and 2017 in Europe and the U.S. What do you think Girard has to tell us about our current time and the highly polarized world in which we currently live?

Want to know what I answered? Check it out here.

The desire to find scapegoats and to invest individuals – whether women, ethnic minorities, Nazi collaborators or modern power figures – with the murderous guilt of an entire tribe or civilization also produces an “opposite” phenomenon: the sacred anointing of martyrs. “Human society begins from the moment symbolic institutions are created around the victim, that is to say when the victim becomes sacred,” Girard explained. Think Iphegenia and Helen of Troy,

The desire to find scapegoats and to invest individuals – whether women, ethnic minorities, Nazi collaborators or modern power figures – with the murderous guilt of an entire tribe or civilization also produces an “opposite” phenomenon: the sacred anointing of martyrs. “Human society begins from the moment symbolic institutions are created around the victim, that is to say when the victim becomes sacred,” Girard explained. Think Iphegenia and Helen of Troy,  Though he was ultimately elected to the prestigious L’Académie Française, Girard was certainly never as celebrated or as controversial as many of his French contemporaries. Haven therefore deserves much credit for choosing to explore Girard’s life and work. The philosopher drew from a careful study of anthropology, history, and literature to illuminate, even presage the repeat cycles of horror and violence in 20h and 21st century life. And Haven draws important connections between Girard’s work and the salient examples of mob violence and martyrdom creation in America – for example, the murders of blacks during the Civil Rights Era, the attacks of September 11, 2001, the shootings and riots in Baltimore, and lately, the mass beheadings of Americans – on video – by ISIS.

Though he was ultimately elected to the prestigious L’Académie Française, Girard was certainly never as celebrated or as controversial as many of his French contemporaries. Haven therefore deserves much credit for choosing to explore Girard’s life and work. The philosopher drew from a careful study of anthropology, history, and literature to illuminate, even presage the repeat cycles of horror and violence in 20h and 21st century life. And Haven draws important connections between Girard’s work and the salient examples of mob violence and martyrdom creation in America – for example, the murders of blacks during the Civil Rights Era, the attacks of September 11, 2001, the shootings and riots in Baltimore, and lately, the mass beheadings of Americans – on video – by ISIS. A belated postscript to

A belated postscript to