René Girard @100: Stanford’s provocative immortel comes of age

Tuesday, June 6th, 2023

(Photo: Linda A. Cicero / Stanford News Service)

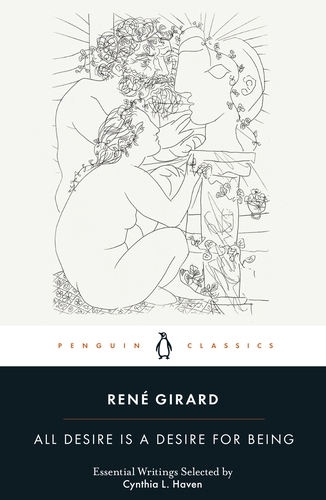

All Desire is a Desire for Being is becoming a reality! I got my advance copies of the new Penguin Classics anthology of René Girard’s “essential writings” this week. (You can pre-order a copy here.) It was an honor to contribute to his legacy with Penguin Classics, as we near his hundredth birthday on Christmas Day. To celebrate, I am republishing an article you may not have seen before. It was published June 11, 2008, by Stanford News Service. I had met the “French polymath” (that’s how the Google “knowledge panel” identifies him nowadays) only a months before. This would become the first of many interviews, essays, and books about the French thinker.

This article and many others from the Stanford News Service are now archived and no longer publicly available. So in the centenary year of René’s birth, I thought I’d make at least this one available to all of you. Enjoy!

The story goes like this: In 2004, Jean-Pierre Dupuy, a professor of French at Stanford, is attending a conference in Berlin when he is confronted by a man in a café who asks, “Why did you become a Girardian?” Dupuy replies in a beat: “Because it’s cheaper than psychoanalysis.”

Did it really happen? Although the event was witnessed, Dupuy responds with a Gallic shrug and an Italian saying: “Si non e vero e ben trovato.” The American equivalent might be Ken Kesey‘s dictum, “It’s the truth even if it didn’t happen.”

In any case, the anecdote illustrates the kind of effect René Girard, the Andrew B. Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature and Culture, Emeritus, at Stanford and one of the immortels of the Académie Française, has had on people. Aficionados of the scholar even have a name: Girardians.

Mimesis and Theory: Essays on Literature and Criticism, 1953-2005, published this spring by Stanford University Press, explores the literary side of Girard’s thinking over his long career-a career that originally focused on literary scholarship but that has gradually embraced anthropology, religion, sociology, psychology, philosophy and theology. French Professor Michel Serres, another immortel (America has only two, and both are at Stanford), has called him “the new Darwin of the human sciences.”

Girard’s Achever Clausewitz, published last year in France by Editions Carnets Nord, will be published in English by Michigan State University Press this winter. The book, which takes as its point of departure the Prussian military historian and theorist Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831), is considered by many to be groundbreaking. Its implications place Girard, known mostly for his studies of literature and archaic cultures, squarely in the 21st century.

“It doesn’t take much insight to realize that wars have been getting worse every time – worse from the point of view of the civilian, more and more destructive, more and more total. Well, Clausewitz is about that,” Girard explained. “Therefore my book is a very end-of-the-world sort of thing.”

Girard lives a sequestered life in the academic burrows of Stanford, but his influence abroad is seismic. Even French President Nicolas Sarkozy cites his writings. While Girard walks the Stanford campus virtually unnoticed and unrecognized, in Paris, visitors say, reporters were on his doorstep every day after the publication of last year’s book.

(Photo: L.A. Cicero)

The “Girard Effect” may become more prominent worldwide with a foundation, Imitatio, that has been established to promote his ideas. (Dupuy is its director of research.) Imitatio launched its research program with a conference at Stanford in April, with about 40 scholars from around the world attending. The Colloquium on Violence and Religion, an independent association of international scholars, also studies mimetic theory and publishes an annual journal, Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis and Culture.

Although Girard will turn 85 on Dec. 25 (he was born in Avignon), he is not resting on his laurels. Achever Clausewitz signals a new development of his line of thought, and he is already working on his next book, which will focus on St. Paul. Are there any more projects envisioned?

“Thousands more!” Benoît Chantre, his French editor and interlocutor for Achever Clausewitz, said and smiled.

Scapegoats and sacrifice

Girard’s thinking, including textual analysis, is a sweeping reading of human nature, human history and human destiny. His contention is controversial: Religion is not the cause of violence, as many suppose; it was, in archaic societies, a way of solving it.

Here’s why: People are social creatures, and their behavior is based on imitation to a much greater degree than generally supposed. How else to explain why a generation decides at once to pierce their tongues, or why stocks rise and fall? How to explain how a child learns language? Even our desires are not our own; we learn them from others.

“We don’t even know what our desire is. We ask other people to tell us our desires,” he said during a lecture at Stanford’s Old Union in February. “We would like our desires to come from our deepest selves, our personal depths – but if it did, it would not be desire. Desire is always for something we feel we lack.”

Envy and resentment are the inevitable consequences of this drive toward mimesis. These emotions, in turn, fuel conflict; it occurs whenever two or more “mimetic rivals” want the same thing, which can go to only one. It might be a woman, a presidency or a research grant. Many religious prohibitions are meant to regulate and control such

conflict.

“When we describe human relations, we lie,” Girard said. “We describe them as normally good, peaceful and so forth, whereas in reality they are competitive, in a war-like fashion.”

In literature, such mimetic desire can create comic masterpieces: A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a classic he frequently cites. Or it can inspire the novels of Balzac, in which the characters strive to outdo each other in snobbery and imitative social values. Such imitation can even be totally imaginary. Don Quixote wishes to be a knight errant, because he is imitating the heroes in the books he has read.

On a societal level, such conflict seeks a release, and the outlet is a scapegoat. A third party-often an outsider, a foreigner, a woman, someone who is disabled, the king or president-is blamed and demonized for having caused the conflict. Scapegoats are not seen as innocent victims; they are seen as the guilty cause of the disorder. The calls mount for the sacrificial victim, and the mob itself creates a sense of harmony.

“Joining the mob is the thing that people don’t realize. They feel the unity but don’t interpret it as joining the mob,” Girard said.

The mob prevails. The victim is killed, exiled, pilloried or otherwise dispensed with. Rivals reconcile, and peace and unity are restored to the community.

“If you scapegoat someone, it’s a third party that will be aware of it,” he said. “It won’t be you. Because you will believe you are doing the right thing. You will be either punishing someone who is guilty or fighting someone who is trying to kill you, but you are never the one who is scapegoating.”

In a sleight of hand that unsettles Girard’s critics, the fact that there is no proof is proof. It is not that the scapegoaters suppress the history of their scapegoating, he said, “scapegoating itself is the suppressing.”

For this reason, tragedy and religion in ancient Greece are inextricably entwined. Take the story of Oedipus. A plague is destroying Thebes, and whom does the mysterious oracle find at fault? The outsider, the lame newcomer king, whose expulsion brings peace to the city-state. Euripides’ The Bacchae is the same-disorder is tearing apart the society and the women are going crazy. Pentheus, the young leader, is at fault-his collective murder brings sanity and harmony to Thebes.

“The first culture which rebels against that system is the Jewish culture,” Girard said. He explains that the Bible is actually counter-mythical. Over a period of centuries, the books of the Old Testament begin to catch on to mankind’s scapegoating mechanism. While they describe and even celebrate violence, they gradually begin to question and fight it as well.

For example, many of the psalms “show a narrator who is surrounded by a crowd of good-for-nothings, who are trying to encircle him and turn him into a victim.” The story of Job also is revealing: “It’s a small community, but he’s been the dictator for years. Everybody loves him, he does no one any harm,” Girard said at the Old Union lecture. “One fine morning he wakes up, and everybody is against him. His three ‘friends’ are ready to explain how bad he is now. And everybody is ready to explain how bad he is at the same time. He has turned from the absolute hero to the scapegoat of the community. Job is like a long psalm and shows you what happens to communities. No myth will ever show you that.”

The climactic victimization is with “the announcement of what we call the Passion.”

“Jesus accepts to be the victim, and we don’t really know why,” he said. “There, what the Gospel said is that it is God himself who has allowed all this scapegoating, and says, ‘You can forgive me, since now I am ready to become your victim myself.'”

Thus, the world has arrived at a dangerous point, Girard said. The mechanism of scapegoating has been seen through; the escape valve is gone. War no longer “works” and no longer resolves mimetic rivalry among nations. While wars were once organized and carried out by states, concluding with a treaty and one side’s defeat, now individual actors can instigate acts of war in a free-for-all. Moreover, the actors may insist on their own martyrdom to aggravate the conflict, rather than resolve it.

In an interview in Le Point last year, Girard presented the dire worldview that made Achever Clausewitz controversial: “The world wars marked an important step in the rise of extremes. September 11, 2001, was the beginning of a new phase. Today’s terrorism still has to be thought through, because we haven’t yet grasped that a terrorist is ready to die in order to kill Americans, Israelis or Iraqis. What’s new here in relation to Western heroism is that suffering and death are called for, if necessary by experiencing them oneself.” We search in vain for scapegoats: “The Americans made the mistake of ‘declaring war’ on al-Qaida without knowing whether al-Qaida exists at all.

“The era of wars is over: From now on war exists everywhere. Our era is one of universal action. There’s no longer any such thing as an intelligent policy. We’ve almost reached the end.”

An existential downfall

Girard’s misgivings about war and a potential apocalypse are the extension of a long thought that has evolved over decades. The road was marked by various points of illumination: One light-bulb moment occurred during a “conversion” experience when he was a young professor at Johns Hopkins University in the late 1950s.

He explained to James Williams, in an interview included in The Girard Reader, the epiphany that was connected with the writing of his first book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel: “I started working on that book very much in the pure demystification mode: cynical, destructive, very much in the spirit of the atheistic intellectuals of the time. I was engaged in debunking, and of course recognizing mimesis is a great debunking tool because it deprives us moderns of the one thing we still have left, our individual desire.”

“The debunking that actually occurs in this first book is probably one of the reasons why my concept of mimesis is still viewed as destructive,” he said. “Yet I like to think that if you take this notion as far as you possibly can, you go through the ceiling, as it were, and discover what amounts to original sin. An experience of

demystification, if radical enough, is very close to an experience of conversion.”

He described his eventual realization this way: “The author’s first draft is a self-justification.” It may either focus on a wicked hero, the writer’s scapegoat, who will be unmasked by the end of the novel; or it may have a good hero, the author’s alter ego, who will be vindicated at novel’s end.

If the writer is a good one, he will see “the trashiness of it all” by the time he finishes his first draft-that it’s a “put-up job.” The experience, said Girard, shatters the vanity and pride of the writer. “And this existential downfall is the event that makes a great work of art possible,” Girard said.

While he speaks easily of conversion, original sin and redemption, however, one visiting scholar wondered why he seemed to circumvent a related theme: the imperative topic of forgiveness. But it’s hard to beat Girard at his own game. Only a few months earlier, Girard had spoken at an informal philosophical reading group in History Corner for several dozen faculty and students.

Girard recapitulated the story of the Old Testament Joseph, son of Jacob, bound and sold into slavery by his “mob” of 10 half-brothers: “They all get together and try to kill him. The Bible knows that scapegoating is a mob affair.” Joseph reestablishes himself as one of the leaders of Egypt and then tearfully forgives his brothers in a

dramatic reconciliation. It is, he said, a story “much more mature, spiritually, than the beginning of Genesis.”

The story is unlike any in archaic literature: “It’s a very beautiful story, which like many biblical stories, is a counter-mythical story,” he said, “because in myth, the lynchers are always satisfied with their lynching.”

But at the reading group, he suggested his audience might not have noticed this before. After all, they had been trained to think that the Bible was a completely backward book, superceded and preceded by better efforts, with little that was new to the world. In short, Girard dropped the cat among the pigeons.

They erupted into debate. Girard slouched back in his chair a little, smiling softly and watching the feathers fly.

Is nuclear holocaust inevitable? Can we back away from the cliff we have been anxiously gazing over for 70 years – or in many cases, simply trying to ignore? Some say there’s no turning back. The German philosopher Günther Anders noted, after his visit to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1958: “Now that humanity is is capable of destroying itself, nothing will ever cause it to lose this ‘negative all-powerfulness,’ not even a total denuclearization of the world’s arsenals. Now that apocalypse has been inscribed in our future as fate, the best we can do is to indefinitely postpone the final moment. We are living under a suspended sentence, as it were, a stay of execution – a reprieve.”

Is nuclear holocaust inevitable? Can we back away from the cliff we have been anxiously gazing over for 70 years – or in many cases, simply trying to ignore? Some say there’s no turning back. The German philosopher Günther Anders noted, after his visit to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1958: “Now that humanity is is capable of destroying itself, nothing will ever cause it to lose this ‘negative all-powerfulness,’ not even a total denuclearization of the world’s arsenals. Now that apocalypse has been inscribed in our future as fate, the best we can do is to indefinitely postpone the final moment. We are living under a suspended sentence, as it were, a stay of execution – a reprieve.”