Geoffrey Hill and the “unwitting travesty of the ‘authentic self.'”

Friday, July 1st, 2016

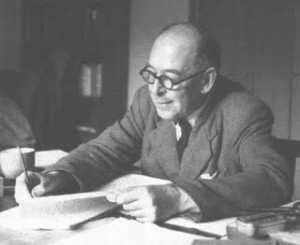

Asked if he liked a particularly severe photograph of himself, he replied: “It terrifies me.”

Geoffrey Hill is gone. The 84-year-old English poet’s death was announced on Twitter at 2.49 a.m. on Friday by his wife, the librettist Alice Goodman. “Please pray for the repose of the soul of my husband, Geoffrey Hill, who died yesterday evening, suddenly, and without pain or dread,” she wrote. You can read more about it here, in The Guardian or in the New Statesman here. Many thought he was the greatest living poet in the English language.

Hill’s death returned me to his 2000 Paris Review interview with Carl Phillips. I’m still reading it. Meanwhile, a few excerpts below; the whole thing is here.

INTERVIEWER

What comes up often in reviews of your work is the idea of an overly intellectual bent; in recent reviews of The Triumph of Love, often the word difficult comes up. People mention that it’s worth going through or it isn’t worth going through.

HILL

“Inner exile”

Like a Victorian wedding night, yes. Let’s take difficulty first. We are difficult. Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other. And we are mysteries to ourselves, we are mysteries to each other. One encounters in any ordinary day far more real difficulty than one confronts in the most “intellectual” piece of work. Why is it believed that poetry, prose, painting, music should be less than we are? Why does music, why does poetry have to address us in simplified terms, when if such simplification were applied to a description of our own inner selves we would find it demeaning? I think art has a right—not an obligation—to be difficult if it wishes. And, since people generally go on from this to talk about elitism versus democracy, I would add that genuinely difficult art is truly democratic. And that tyranny requires simplification. This thought does not originate with me, it’s been far better expressed by others. I think immediately of the German classicist and Kierkegaardian scholar Theodor Haecker, who went into what was called “inner exile” in the Nazi period, and kept a very fine notebook throughout that period, which miraculously survived, though his house was destroyed by Allied bombing. Haecker argues, with specific reference to the Nazis, that one of the things the tyrant most cunningly engineers is the gross oversimplification of language, because propaganda requires that the minds of the collective respond primitively to slogans of incitement. And any complexity of language, any ambiguity, any ambivalence implies intelligence. Maybe an intelligence under threat, maybe an intelligence that is afraid of consequences, but nonetheless an intelligence working in qualifications and revelations . . . resisting, therefore, tyrannical simplification. …

INTERVIEWER

Poet and martyr

Do you see yourself as a kind of martyr figure, in terms of your being a poet, and in the context of what we’ve said about people not understanding issues of difficulty or possibilities for intelligence?

HILL

No, absolutely not. My interest in the Elizabethan Jesuits, and in particular Robert Southwell and Edmund Campion, is that they seem to me to be transcendently fine human beings whom one would have loved to have known. The knowledge that they could so sublimate or transcend their ordinary mortal feelings as to willingly undertake the course they took, knowing what the almost inevitable end would be, moves me to reverence for them as human beings and to a kind of absolute astonishment. The very fact that they lived ennobles the human race, which is so often ignoble. I also have to admit that I contemplate them to in some way exorcize my own terror of terminal agony. I can go with them to the point where my own emotional endurance can go no further.

***

Again, taking a long, historical view, I can understand why I was impressed by Eliot’s contempt for the “inner voice.” I would still maintain that a considerable amount of the very unsatisfactory stuff that is being written now is unwitting travesty of the “authentic self.” The particular tone of the unsatisfactory changes from period to period, the unsatisfactory poetry of the age of Pope is not quite the same sort of creature as bad poetry in the age of Tennyson, and bad poetry in the age of Tennyson differs from the bad poetry of the present time. A great deal of the work of the last forty years seems to me to spring from inadequate knowledge and self-knowledge, a naive trust in the unchallengeable authority of the authentic self. But I no longer think that the answer to this lies in the suppression of self; it requires a degree of self-knowledge and self-criticism, which is finally semantic rather than philosophical. The instrument of expression and the instrument of self-knowledge and self-correction is the same. There is a kind of poetry—I think that the seventeenth-century English metaphysicals are the greatest example of this, Donne, Herbert, Vaughan—in which the language seems able to hover above itself in a kind of brooding, contemplative, self-rectifying way. It’s probably true of the very greatest writers. I think it’s true of Dante and Milton, and I think it is true of Wordsworth. It’s a quality that these poets possess supremely. The rest of us, even the very best of us, possess it to a lesser and differing degree, but I cannot conceive poetry of any enduring significance being brought into being without some sense of this double quality that language has when it is taken into the sensuous intelligence, and brought into formal life.

Again, taking a long, historical view, I can understand why I was impressed by Eliot’s contempt for the “inner voice.” I would still maintain that a considerable amount of the very unsatisfactory stuff that is being written now is unwitting travesty of the “authentic self.” The particular tone of the unsatisfactory changes from period to period, the unsatisfactory poetry of the age of Pope is not quite the same sort of creature as bad poetry in the age of Tennyson, and bad poetry in the age of Tennyson differs from the bad poetry of the present time. A great deal of the work of the last forty years seems to me to spring from inadequate knowledge and self-knowledge, a naive trust in the unchallengeable authority of the authentic self. But I no longer think that the answer to this lies in the suppression of self; it requires a degree of self-knowledge and self-criticism, which is finally semantic rather than philosophical. The instrument of expression and the instrument of self-knowledge and self-correction is the same. There is a kind of poetry—I think that the seventeenth-century English metaphysicals are the greatest example of this, Donne, Herbert, Vaughan—in which the language seems able to hover above itself in a kind of brooding, contemplative, self-rectifying way. It’s probably true of the very greatest writers. I think it’s true of Dante and Milton, and I think it is true of Wordsworth. It’s a quality that these poets possess supremely. The rest of us, even the very best of us, possess it to a lesser and differing degree, but I cannot conceive poetry of any enduring significance being brought into being without some sense of this double quality that language has when it is taken into the sensuous intelligence, and brought into formal life.

.