Lena Herzog on lost languages: “We are floating on an ocean filled with the silence of others.”

Friday, April 6th, 2018

Photographer Lena Herzog at work.

Our post a few days ago about lost languages evoked some interesting responses – one of them from photographer Lena Herzog. Lena has made an occasional appearance in the Book Haven, and I interviewed her for Music & Literature here. She was a guest panelist at the Another Look book event on Dostoevsky, and her Entitled Opinions interview got record traffic.

As a result of our conversation, she offered us a guest essay on the origins of “Last Whispers/Oratorio for Vanishing Voices, Collapsing Universes, and a Falling Tree,” which was mentioned on the post several days ago. “I got addicted to these vanishing voices,” she writes:

At the age of six I decided to learn English so that I could understand a puzzle in a Sherlock Holmes story. I had to know how the detective had decoded a death threat to his client’s wife in The Adventure of the Dancing Men. The key to that puzzle was the recognition of the recurring definite article “the”—a mysterious notion to me then since articles do not exist in Russian. I grew up in the Urals, on the western border of Siberia, where very few people spoke foreign languages. I picked up Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original in English, along with a dictionary and a grammar text book, and struggled through the entire book line by line. Later, also prompted by the desire to read literature in the original, I studied French and Spanish and, worked as a proof-reader at a printing press in Saint Petersburg, next to the compositors that were busily nestling letters into words, words into sentences, and sentences into novels at a staggering speed, throwing proofs over to me like hot bread. So it made sense to me that when I went to Saint Petersburg University, the door plaque of my faculty read philology φιλολογία—including the original Greek, which means “love of the word.” However, all my plans to become a Russian novelist were upended by a complete linguistic dislocation to American English at age twenty, when I moved to the United States. The sense of personal language loss was concrete and overwhelming, alerting me to a far more universal and dire fate for most languages.

The idea for a project specifically on the mass extinction of languages came to me more than two decades ago. My old failed 2003 Guggenheim application was titled “Vanishing Cultures” and was at first, in part, a photographic project. I’d planned to take large-format portraits of the last speakers of various languages and place them in a room filled with their whispering voices. The concept of sounding vanished voices by broadcasting them as a muffled chorus was already central and clearly articulated in my description of the project back then.

I realized that indigenous communities give up their languages and switch to dominant ones under pressure from the forces of globalization. My next natural iteration of this idea involved shedding the images of the speakers and having only voices in a forest. When a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, does it make a sound? This old philosophical trope, the basic epistemological exercise, seemed handy. What is our sense of the unobserved, unheard worlds? I have come to think of this old exercise as one in empathy: Does it matter that trees and universes collapse all around us? Somewhere, between our obliviousness to others and our own oblivion, rest the scales of some brutal justice.

The British Museum installation of “Last Whispers.”

My team and I began amassing a giant library of recordings of extinct and endangered languages on loan from international archives, working closely with many collections, linguists, and anthropologists in the field. Our main collaborator was the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme, a project of SOAS University of London that is headed by Mandana Seyfeddinipur. When I went through their archives online, I realized there would be no point in just “stacking” languages back-to-back to form a single piece. Because these recordings were already public, generously so, it would have been possible to perform this kind of compilation just by clicking “next” on their website, and that would have been too obvious a gesture for the work I had in mind.

While working in my studio and darkroom, I created a setup that randomly played thousands of these recordings, one after another. I marked those that felt right for the oratorio I was planning and began narrowing down the library. The extraordinary researcher Theresa Schwartzman, in Los Angeles, and her counterpart in London, Eveling Villa, began reaching out to archives, linguists, and indigenous communities (when this was possible) to obtain rights and permissions for the recordings. Sometimes there was no community to reach. We went beyond the letter of the law, which held that the copyright resided with the linguists and the archives, and tried to reach those who claimed heritage to the language. Sometimes last speakers changed their minds, turning us down mid-composition and mid-film, and we had to redo the work from scratch. Each case had a story, most often a tragic one. We began to publish some of them on our website.

Mandana Seyfeddinipur and Lena Herzog

Every dialogue with a linguist, no matter how banal, brought insight. The professionals who travel and live among these last speakers are the unsung heroes in this story; they are the ones who collect, preserve, and help revitalize endangered languages. In my dealings with them, they were the advocates for the last speakers’ rights. One might think that they would number enough to form an army, but there are barely enough of them for a battalion. Most work alongside volunteers and language enthusiasts. And all of them, at least those that I have met, are on the side of indigenous peoples. To put it in espionage terms, linguists of endangered languages almost always “go native.” They are the ones who hear the trees falling in the forest. Our long list of credits names both the speakers and the linguists—meticulously.

The polyphonic global chorus that I heard had the makings of an astonishing oratorio, and to bring it into a public space beyond the form of the archive, I needed music and imagery that would reveal it in a condensed form. This form had to be invented organically; it had to come from the recordings, from the voices themselves.

Marco Capalbo and Mark Mangini, who work fluidly in both sound design and composition, joined the team, and we began to shape the oratorio from our already-narrowed library. My concept was multilayered and concrete: it included the use of sounds of Russian bells, forest noises, wind, interpreted gravitational waves from outer space registered by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (a.k.a. “the Listening Ear”), and the specific parameters for the source library itself. In my first brainstorming session about the work, I wrote to Marco and Mark:

Lena Herzog’s team Marco Capalbo, Mark Mangini and British Museum curator David Sheldon during the installation

What is the balance of the piece? What holds it together?

The “founding idea” of making the work is based on the recordings of languages that had already vanished or are well on their way to extinction. The parameters within which the selection was made for the source library—I have defined. This is clearly a glue as the overall idea and basic building blocks. … Using cosmic sounds of the universe within the composition expands the arc. Gives us “eternal” time. … I really love the opening with the bell. The end will have to be a giant chorus that builds and builds and then abruptly vanishes—in an exhale.

Shifting from fragmentation to a lyrical cradling of the voices, then back to fragmentation, and ending with a finale of interwoven harmony and dissonance were key to the piece I was constructing with my team.

Listening to the sounds of the voices and the first sketches by Marco and Mark, the photographer Tomas van Houtryve and I mapped a precise choreography of drone footage. Animator Amanda Tasse and I decided to create a new topography for the world that would have no “real” geography. We collected NASA images of hurricanes, cut out their edges, and sewed them together, forming something like a digital quilt to cover the earth. I thought that the edges of these vortices textured the continents and islands well, lighting the globe like a strange marble.

There is lamentation and melancholy in the oratorio. How can it be otherwise? And yet it is not a requiem—it is an invocation of languages that have gone extinct and an incantation of those that are endangered. I myself got addicted to these vanishing voices. I listen to them all the time now. They remind me that despite the deafening noise of our own voices, we are floating on an ocean filled with the silence of others.

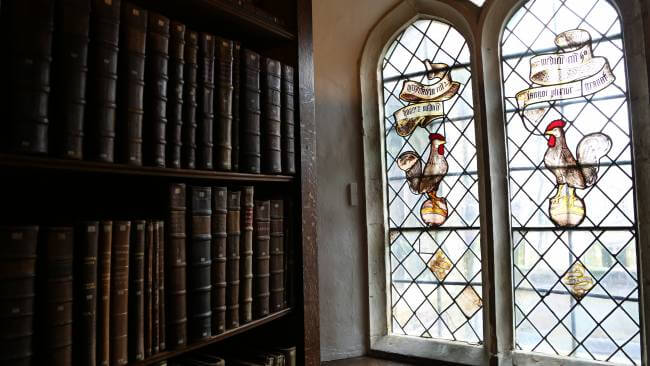

But the Algonquin Bible haunted me for another reason: I recently attended a private screening in San Francisco of photographer’s

But the Algonquin Bible haunted me for another reason: I recently attended a private screening in San Francisco of photographer’s

Haven: So how do you capture a moment that is movement? With the Strandbeests, you’re trying to take a still photograph of something that is essentially motion, by definition.

Haven: So how do you capture a moment that is movement? With the Strandbeests, you’re trying to take a still photograph of something that is essentially motion, by definition. That connection is what matters, what makes me take a picture. That’s why, for example, I don’t use tripods. I have them, I just haven’t used them. I realized that even when I’m photographing a tree or a mummified human specimen in the Cabinet of Wonders I need to be one with my camera. The lost souls are not moving, but I am moving. My soul is moving. It’s breathing. It feels like I fall into breathing with the world. And then I click.

That connection is what matters, what makes me take a picture. That’s why, for example, I don’t use tripods. I have them, I just haven’t used them. I realized that even when I’m photographing a tree or a mummified human specimen in the Cabinet of Wonders I need to be one with my camera. The lost souls are not moving, but I am moving. My soul is moving. It’s breathing. It feels like I fall into breathing with the world. And then I click.