Visiting old friends in Kraków…

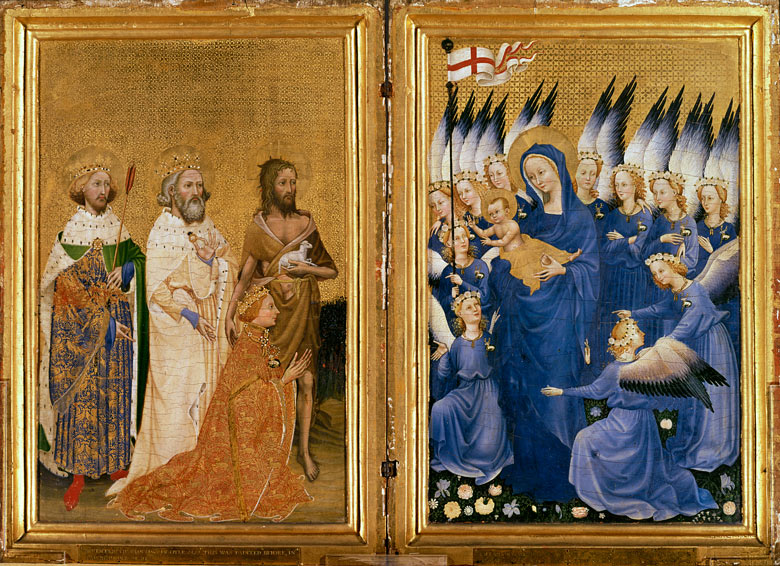

Wednesday, July 10th, 2024I paid a visit to an old friend today. Last time we visited was six years ago at her temporary digs in Wawel Castle, on a bitterly cold winter day in Kraków – and Polish winters have a sharp bite that has to be experienced to be believed. She was only about two feet away from my face, and no one else was around – as a friend observed, the experience changes when you can see the craquelure up close.

Today she seems to have found a more permanent home at the Muzeum Czartoryskich. Leonardo da Vinci’s 21″ x 15″ oil painting is one of Poland’s great treasures. Stanford archist Elena Danielson described her as “wonderful in person, and much finer and far more mysterious than the Mona Lisa.”

Joy Zamoyski Koch commented on the provenance of the painting: “Lady with an Ermine was purchased in 1798 by Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski for his mother (my 4th grandmother) Princess Izabella and incorporated into the family art collection at Pulawy (which is also a museum worth visiting).

“She rescued it from the invading Russian army in 1830, sent it to Dresden, then to Czartoryski family in exile in Paris, and finally to Krakow in 1882.

“In 1939, the Germans seized it and sent it to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin. The following year, Hans Frank, the Governor General of occupied Poland, requested its return to Krakow. In 1945 it was taken to Frank’s country home in Bavaria, where it was duly liberated by American troops who returned it to the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków.”

Said one of my bros: “Very cool! I have liked that painting for many years – the ferret and girl have the same look on their faces.” How many people have noticed that?