How the cult of personality turns everyone into a liar

Wednesday, July 27th, 2016

Not a dictator, but a scholar. (Photo: Rachel Moltz)

When Mao Zedong died on September 9, 1976, hundreds of thousands of people poured into the streets, weeping over the dictator who is responsible for at least 50 million deaths.

According to Frank Dikötter of the University of Hong Kong, the cult of personality turns everyone into liars. “These are not true tears,” he told an audience at the Hoover Institution last week. “It’s not really clear who is really crying. Everyone knows there is lying. Not everyone knows who is lying.”

Dikötter is the author of Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, which won the 2011 Samuel Johnson Prize, Britain’s most prestigious book award for non-fiction. He spoke at Hoover about “The Making of the Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century.” He is working on a “global history of the cult of personality,” focusing on prominent dictators of the 20th century.

“Millions were led to the death as they cheered their master,” said Dikötter of Mao. “The cult of personality obliged everyone to become a sycophant, destroying their dignity in the process.”

The Dutch author quoted Dostoevsky‘s Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov, saying the ruler has two tools at his disposal: on one hand magic and mystery, on the other, the sword. Yet “the cult of personality” is born of the age of democracy. “Dictators depend on popular support,” he said. A totalitarian ruler needs at least the illusion of a mandate at the ballot box.

Romania’s man about town.

“The rise and fall of dictatorships is often determined by the cult of personality,” Dikötter said. The creation of the cult is far from a solo effort; a dictator needs plenty of support. “There is, at least, a ministry of propaganda, an army of photographers, bureaucracy, whole sections of industry, the army.” Mao, for example, had a whole industry to produce cult objects. Under Pol Pot, who caused the death of millions, a whole prison was dedicated to printing images of the leader and developing cult objects. Dikötter said the regime failed precisely because Pol Pot was unable to establish himself as a cult personality.

Dikötter noted that there were some excellent studies on the cult of personality, although in many cases scholarly efforts remain scattered. In the case of Germany, for instance, the first exhibition of cult objects about Hitler took place only five years ago. “It seems almost obscene to look at the shiny surfaces the state produces rather than at the horror it hides,” he said.

The shiny surfaces also have a practical purpose: “In a dictatorship, you develop the image and the cult so that you will not have to turn to force. That’s the point.”

Forever young.

The ministry of propaganda, photographers and others have plenty of work to do. For example, Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu traveled the country so much that he seemed to be everywhere at once. He made a record 147 whistle-stop tours of the entire country between 1965 and 1973. Some regimes rubbed out the images of fallen aides and sidekicks from photos (Milan Kundera famously describes how Vladimír Clementis was erased in a 1948 photo when he fell from favor). Ceaușescu went one step further: he had himself inserted himself into photos of meetings he never attended, sometimes meetings that occurred at the same time miles away from each other, suggesting a sort of bilocation. After his fall, the cult images came down very rapidly.

Adolf Hitler, author of the Holocaust, buffed his image throughout the 1930s. Popular images portrayed him as a vegetarian, non-drinking, non-smoking, hard-working, modest man – and not just in Germany. “You can read it in the New York Times,” said Dikötter – dictators make a point of courting the foreign press and journalists, and the favor is apparently returned. The Hitler Nobody Knows (1933) was almost a companion volume to Mein Kampf. Hitler is always seen without his glasses.

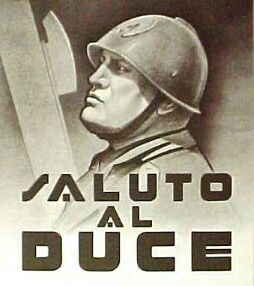

Propaganda presented Benito Mussolini as “good family man, a far-seeing statesman, a stern dictator,” said Dikötter. The voice of the leader is an important tool in the legend, and Mussolini used it for maximum effect in his balcony speeches – ““a metallic voice with sentences delivered like the blows of a hammer.” While many of Italy’s poor did not have ready access to the radio, loudspeakers suddenly appeared in the public square, to make sure they got the message.

By contrast, genocidaire Joseph Stalin hardly speaks at all, but that’s just as important. He appears before millions of the Red Guards and says nothing. “By not speaking he becomes the center of gravity,” said Dikötter.

By contrast, genocidaire Joseph Stalin hardly speaks at all, but that’s just as important. He appears before millions of the Red Guards and says nothing. “By not speaking he becomes the center of gravity,” said Dikötter.

Ceaușescu, like the other dictators Dikötter studied, drew his inspiration from others. In his travels, “he was smitten by what he sees in China and Korea – he takes it quite seriously,” said Dikötter. “Dictators don’t do this on their own.”

They draw their lessons not only from other lands, but other histories. They must present themselves in an imaginative line of succession rather than as illegitimate upstarts who grabbed power. Thus, Stalin presides over the canonizing of Lenin. The Ethiopian genocidaire Mengistu Haile Mariam, responsible for killing 500,000 to 2,000,000 people, adopted the symbols and trappings of the Emperor Haile Selassie, whom he had killed and buried beneath the palace, before turning to Marxism-Leninism. Mussolini presented himself as the reincarnation of Caesar Augustus.

Kim Il-sung presented himself as the tradition of thousands of years embodied in his very own person. “It’s difficult to pull it off, unless you have a hermetically sealed state, like North Korea,” said Dikötter.

“Papa Doc” Duvalier in Haiti, who killed 30,000 to 60,000 of his countrymen, was the only one who reached into another world for his authority. He used voodoo as a prop to develop his cult of personality, and he took it very seriously. He came across to his minions as a gentle person in dark glasses, half-mumbling as if he were casting spells.

Yes, someone asked, but what happens when the dictator becomes sleek and very fat. Surely the starving and impoverished workers are no longer bedazzled by the ugly frog that waddles before them?

“Once the image develops, it tends to stay fixed,”said Dikötter. “It stays fixed and ever youthful, even though Mao in his last years looked pretty ghastly,” with black teeth, Lou Gehrig’s disease and, yes, very overweight.

The funeral of Mao: faking it.