Brodsky Among Us in English, and “the only form of moral insurance that a society has.”

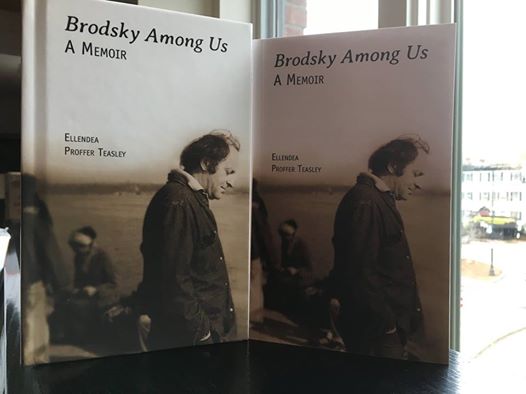

Wednesday, August 30th, 2017 Marat Grinberg writes about Ellendea Proffer Teasley’s Brodsky Among Us over at Commentary. The article was published in June, but it was easy to overlook during this eventful summer. Also easy to overlook: Brodsky Among Us, which I wrote about for The Nation, is now in English, published by Academic Studies Press (on Amazon here).

Marat Grinberg writes about Ellendea Proffer Teasley’s Brodsky Among Us over at Commentary. The article was published in June, but it was easy to overlook during this eventful summer. Also easy to overlook: Brodsky Among Us, which I wrote about for The Nation, is now in English, published by Academic Studies Press (on Amazon here).

“The publisher Ellendea Proffer Teasley’s memoir of the poet, which became a sensation when it was first published in Russian three years ago, provides a penetrating and at times deeply moving account of both the myth and the man behind the work,” writes Grinberg. “She renders the Brodsky she knew not just as a great poet and deeply imperfect human being, but also as a political thinker who was uncompromising and unforgiving in his beliefs.”

“Proffer writes of Brodsky’s ‘determination to live as if he were free in the eleven-time-zone prison that is the Soviet Union.’ She emphasizes that his opposition to the Soviet power was presented in starkly moral terms: ‘A man who does not think for himself,’ she writes, ‘a man who goes along with the group, is part of the evil structure himself.’”

The Commentary article, in a magazine founded by the American Jewish Committee in 1945, takes on the Nobel poet’s Jewishness, a subject he himself didn’t dwell on, to put it mildly. An excerpt:

Proffer and the poet in Petersburg.

Proffer implicitly links Brodsky’s Jewishness to this resistance to the “evil structure.” It is a primary subject of their first encounter, which she describes thus: “Joseph is voluble and vulnerable. He brings up his Jewish accent almost immediately; when he was a child, his mother took him to speech therapy to get rid of it, he says, but he refused to go back after one lesson.” The “Jewish accent” had to do with Brodsky’s inability to roll his “r”s, which, while by no means unique to Jews, was a mark of the Jew in the largely anti-Semitic Soviet environment. Brodsky bought into the prejudice and at the same time wore it with pride, making it his own.

Jewishness is an ongoing theme in Brodsky’s early poetry of the 1960s, in which he speaks of a Jewish cemetery on the outskirts of Leningrad and imagines his future “Jewish gravestone.” His “Isaac and Abraham” is a beautiful, tortured and complex midrash on the binding of Isaac. Brodsky transplants the biblical patriarchs onto the Soviet landscape, making the relationship between Abraham and Isaac symbolic of the rift between Russian-Jewish fathers and sons, who are burdened by the loss of Judaism as well as historical traumas both near and distant. The poem reveals Brodsky’s familiarity with Hebrew scripture as well as the kabbalah. In his later poetry, the explicit Jewishness all but disappears in accordance with his goal to become the greatest Russian poet of his era and instead becomes a powerful undercurrent.