First time in English: a powerful Russian voice from the Ukrainian conflict

Monday, August 28th, 2017

A field in the Donbas. (Flickr)

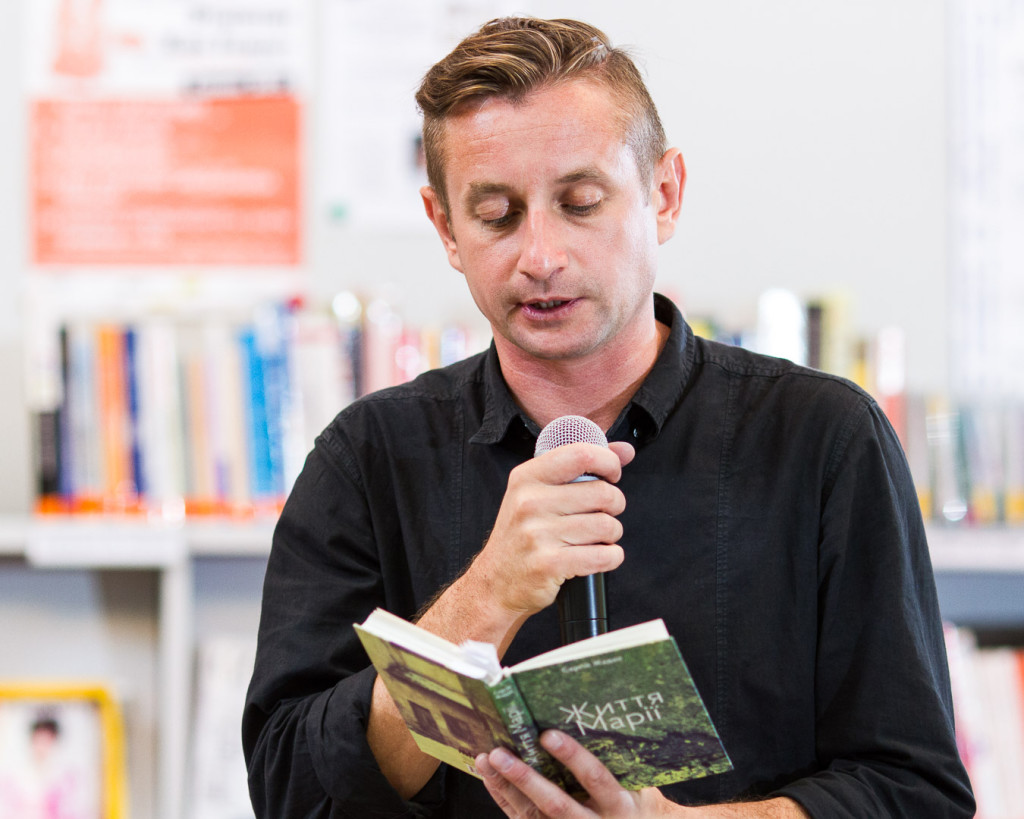

Award-winning Ukrainian writer Vladimir Rafeenko, who writes in Russian, spent his whole life in the city of Donetsk, in the eastern Ukrainian mining region called the Donbas. Since the war between Russian-supported separatists and the Ukrainian state broke out in spring 2014, Rafeenko moved near Kiev.

When the characters in his novels refer to “Westerners,” it’s western Ukraine, facing Poland, Romania, and Hungary rather than Russia.

Ukrainian writer – in Russian.

It’s one of many terms that need unpacking in Семь Укропов (Sem’ Ukropov), in English “Seven Dillweeds,” taken from Rafeenko’s longer work, this year’s Долгота дней (Dolgota dnei, The Length of the Day). “Dillweed,” in the title, is Russian slang for a Ukrainian. Marci Shore, author of The Taste of Ashes: The Afterlife of Totalitarianism in Eastern Europe and Caviar and Ashes: A Warsaw Generation’s Life and Death in Marxism, 1918-1968, translated the piece in the current Eurozine, and explains some of the references for us in the introduction to this chilling short story about the conflict in Rafeenko’s native land, Donbas.

This story is the first time Rafeenko has appeared in English. An excerpt from the excerpt, about Pashka and his stepfather:

Matvei Ivanovich, having appeared out of the blackness of the coalminers’ night, took the boy under his protection, and succeeded in winning his heart.

Matvei Ivanovich had come there at a mature age; he’d come because of his ‘work transfer.’ And as he himself admitted, it wasn’t that he didn’t like Ukraine, it was more that he didn’t understand it. As he would say to the boy he was raising: ‘I don’t understand the Ukrainian language, son, and also all these complicated things with Stepan Bandera. I don’t like westerners, you understand? They’re barbaric somehow. Just barbaric people. And they only hang around with each other. Back at home there were a few of them working at our mine. And they only talked to their own and only in their own way. They even got beaten for that more than once. I don’t think there was any sense in that, though – just made them more spiteful. And so I figure: once you’ve got people like that, what can you do with them?’ …

Matvei Ivanovich tilted his head in a funny way, waved his hands, poured himself another shot of vodka, grabbed a half-salted pickle.

спасибо, Marci.

When the shooting started in town, Matvei Ivanovich proceeded to study the situation. By then he’d already left his job, since he had a solid pension and at any rate the miners weren’t being paid any more. So he had time on his hands to learn about the state of the world. He walked around, talked to people. He would come back in the evening, tired, restless, but generally satisfied.

In the beginning of June, after he’d gotten his pension and the economy had sunk, Matvei Ivanovich was found in a city park, dead. He was lying in water with a sad smile and a deep gash on the right side of his neck. At the burial, Nina Ivanovna sobbed terribly. When they lowered the casket, she jumped into the pit. She tried to stab herself in the heart with a knife. But after a week she found work in the town centre as a janitor in a student dormitory, and in the new job she revived a little.

Pashka saw his stepfather every day in his dreams. There Matvei Ivanovich smiled and told stories, stories without endings and without beginnings, stories about coal, about Aleksandr Nevskii, about Belka and Strelka and the Battle of the Kalka. Truth be told, Pashka just caught the general tone, the details he could only make out hazily, as if through dirty glass. Eventually he signed up for the war against Right Sector, and thus for Gagarin and Gogol, and above all for Matvei Ivanovich, agronomist by his first diploma. They gave the boy a Kalashnikov and two magazine cartridges and sent him to fight with three dozen others like himself. It turned out, unfortunately, that in combat they were not alone – the enemy was there, too. And it quickly became clear that in a war, people kill each other. But truth be told, Pashka didn’t have time to make sense out of any of it.

Read the whole thing here.

The balaclavas and Kalashnikovs and the culture of gangsters are connected to bottomless corruption. The word, or rather one of the words, for corruption in Russian is prodazhnost’ (in Ukrainian, prodazhnist’); it means “saleability” and refers to the understanding that everything and everyone can be bought. A peculiar relationship between prodazhnost’, “saleability,” and chestnost’, “honesty,” belongs to the essence of the Donbas. Where there is no trust in the system, trust in one’s friends is essential. Where there is no law, personal solidarity is paramount. And so what is important is not for whom one votes but how one treats one’s friends. Chestnost’ is related both etymologically and conceptually to chest’, “honor.” What is so striking about Herman’s experiences amid the savagery of the Donbas is the absence of duplicity. Voroshilovgrad is an unsentimental novel about human relationships in conditions of brutality in which there is not a single act of betrayal.

The balaclavas and Kalashnikovs and the culture of gangsters are connected to bottomless corruption. The word, or rather one of the words, for corruption in Russian is prodazhnost’ (in Ukrainian, prodazhnist’); it means “saleability” and refers to the understanding that everything and everyone can be bought. A peculiar relationship between prodazhnost’, “saleability,” and chestnost’, “honesty,” belongs to the essence of the Donbas. Where there is no trust in the system, trust in one’s friends is essential. Where there is no law, personal solidarity is paramount. And so what is important is not for whom one votes but how one treats one’s friends. Chestnost’ is related both etymologically and conceptually to chest’, “honor.” What is so striking about Herman’s experiences amid the savagery of the Donbas is the absence of duplicity. Voroshilovgrad is an unsentimental novel about human relationships in conditions of brutality in which there is not a single act of betrayal.

Mikhail Iossel, author of Every Hunter Wants to Know: A Leningrad Life and contributor to The New Yorker: I am absolutely devastated. I loved him dearly. He was one of the most brilliant, altogether remarkable people I have ever met, one of Europe’s leading public intellectuals, one of world’s most interesting philosophers and social thinkers, an enormously erudite and prolific scholar and a passionate patriot of his country, son of Holocaust survivors and member of the European Parliament – a

Mikhail Iossel, author of Every Hunter Wants to Know: A Leningrad Life and contributor to The New Yorker: I am absolutely devastated. I loved him dearly. He was one of the most brilliant, altogether remarkable people I have ever met, one of Europe’s leading public intellectuals, one of world’s most interesting philosophers and social thinkers, an enormously erudite and prolific scholar and a passionate patriot of his country, son of Holocaust survivors and member of the European Parliament – a The Maidan was the return of metaphysics. It was a precarious moment of moral clarity, an impassioned protest against rule by gangsters, against what in Russian is called proizvol: arbitrariness and tyranny. It united Russian-speakers and Ukrainian-speakers, workers and intellectuals, Ukrainians and Jews, parents and children, left and right. The Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak … described the Maidan as akin to Noah’s Ark: it took “two of every kind.” For Yaroslav, the wonder of the Maidan was the creation of a truly civic nation, the overcoming of preoccupations with identity in favor of thinking about values. People came to the Maidan to feel like human beings, Yaroslav explained. The feeling of solidarity, he said—it cannot be described.

The Maidan was the return of metaphysics. It was a precarious moment of moral clarity, an impassioned protest against rule by gangsters, against what in Russian is called proizvol: arbitrariness and tyranny. It united Russian-speakers and Ukrainian-speakers, workers and intellectuals, Ukrainians and Jews, parents and children, left and right. The Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak … described the Maidan as akin to Noah’s Ark: it took “two of every kind.” For Yaroslav, the wonder of the Maidan was the creation of a truly civic nation, the overcoming of preoccupations with identity in favor of thinking about values. People came to the Maidan to feel like human beings, Yaroslav explained. The feeling of solidarity, he said—it cannot be described.