“The most selfless guardian of Brodsky’s heritage”: Valentina Polukhina (1936-2022), requiescat in pace

Tuesday, February 8th, 2022

She was a woman from another era, in the finest sense of the word. The up-to-date term “networker” would trivialize Valentina Polukhina‘s indefatigable labors – yet never was it more apparent since her death in the early hours this morning how wide her network was. The Keele University professor who was one of the world’s leading scholars on Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky seemed to know everyone, and kept up a wide circle of correspondence. Her Facebook page was flooded with reminiscences and condolences.

She died quietly at her home in Golders Green, London, in the early morning hours of February 8, at age 85. There is no one like her, and no one to take her place. She will be very much missed – and not only in the world of Brodsky scholarship. She was a generous scholar, a kind and wise human being, and a dear friend. She was the recipient of the A. C. Benson Medal and the Medal of Pushkin. Valentina, the widow of translator Daniel Weissbort, will be remembered most of all, I think, for her tireless work on the multi-volume Brodsky Through the Eyes of His Contemporaries. That unique masterwork will grow in importance and meaning with time.

And what a fascinating effort it was: a massive collection of in-depth interviews with those who knew the Russian Nobel poet – including friends from his Leningrad days before his 1972 expulsion from the USSR, which brought him to Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan, and the new friends he made in exile. The volumes include interviews with fellow Nobelists Seamus Heaney, Czesław Miłosz and Derek Walcott, Swedish author Bengt Jangfeldt, Lithuanian poet Tomas Venclova, British author John le Carré, Susan Sontag, and dozens and dozens of others, some famous, others relatively unknown colleagues from Russia. Think of it: a firsthand record of what it was like to live, love, and work with one of the great geniuses of our time. She took flak for this effort – not least of all from Brodsky himself – but I have no doubt these volumes (two in English, three in Russian) will stand the test of time, and be an endless literary and cultural goldmine for generations to come.

Yuri Leving of Dalhousie University, who has written about Brodsky’s artwork, agrees: “While reading obituaries and sketches today about the main and, without exaggeration, the most selfless guardian of Brodsky’s heritage, I involuntarily caught myself thinking of the bright portraits in Brodsky Through the Eyes of his Contemporaries. I took this photograph (above) at her home in Golders Green in August 2010 when her husband, the remarkable poet and translator Daniel Weissbort, was still alive. The following ten years included a few more meetings and regular correspondence – everything about Brodsky was sacred to her, and it could not help but attract her. In 2021, when I was preparing to go to London again, Valentina wrote: ‘Alas, I can no longer cook dumplings. Instead, I will invite you to lunch at my club Athenaeum, where Joseph appeared in jeans at the invitation of Sir Isaiah Berlin. You really need to be in a suit and tie for this.’ My trip was exactly a week after Valentina was discharged from the hospital (she had been injured in a fall) so we agreed to postpone the appointment. Now is forever and ever.”

She was a 21st century networker, but also something from a much older tradition: one of those Russian women (some scholars, some not) who dedicate their lives to a timeless literary figure, one such as Joseph Brodsky. Among her many books: Joseph Brodsky: A Poet for Our Time (Cambridge University Press, 1989, 2009), Brodsky’s Poetics and Aesthetics (Macmillan Press, 1990), Joseph Brodsky: The Art of a Poem (Macmillan Press, St. Martin’s Press, 1999), and others. That’s in addition to the two thick volumes of Brodsky Through the Eyes of His Contemporaries, which I reviewed for The Kenyon Review a decade ago.

From author Maxim D. Shrayer of Boston College: “The passing of Valentina Polukhina, literary scholar best known for her writings about Joseph Brodsky, is a terrible loss. Our family and Valentina have been friends for over twenty-five years. She was endowed with a remarkable and rare talent—to love and cherish poetry and poets, and to do so outside the grid of literary politics. How bitter it is to realize that Valentina Polukhina is gone. Memory eternal.”

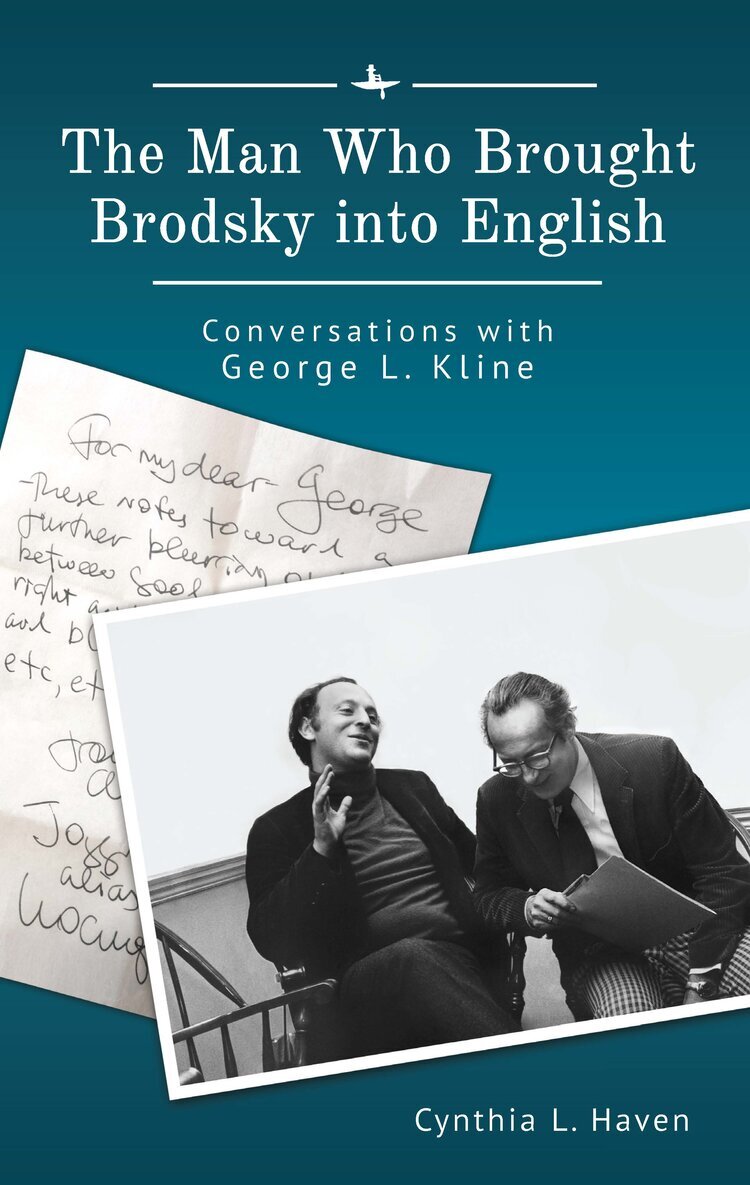

I was a recipient of her generosity during our work with The Man Who Brought Brodsky Into English: Conversations with George L. Kline. She was an invaluable firsthand source. I will always treasure the time we spent together in London back in 2018. The advice she gave, the additional material she supplied from her own rich archive, all enriched the small volume.

She was a matchless hostess as we worked, for she generously invited me to stay in her charming Golders Green home for a week. And that was an unforgttable event, too – a place infused with her history and memories, her Russian taste, her vivid colors, her rich Orthodox heritage, made an indelible impression.

We were going to get together in London to celebrate with champagne the publication of The Man Who Brought Brodsky into English … when the coronavirus epidemic subsided, when travel resumed. Now I will have to lift a glass of bubbly to her memory by myself – here, far away, on the shores of the Pacific.

Postscript on February 11: Over at her blog The Stone and the Star, poet and publisher Clarissa Aykroyd remembers meeting Valentina at a reading: “I asked her about her writing and work and she told me that she had written many books about Brodsky. She then mentioned that her husband was the late Daniel Weissbort. I was a bit dumbfounded – Daniel Weissbort died only a few months ago and I had read many tribute articles and obituaries. He was the founder of Modern Poetry in Translation, along with Ted Hughes. She herself was Valentina Polukhina, not only a Brodsky expert but a major scholar and advocate of Russian literature for English speaking audiences. I told her that I didn’t know a lot about Brodsky but that I adored Mandelstam, and she said “The advantage of Mandelstam is that he has been translated by many different people, so you have a lot of choice.” I also told her, quite sincerely, that I would rather read Modern Poetry in Translation than most journals dedicated to contemporary English-language poetry, and she seemed happy about that. When we introduced ourselves, she said to me that the name Clarissa was also found in Russia, but that it was considered quite aristocratic. It was a lovely, striking encounter.” Read the whole thing here.

Also, Britain’s premier publisher of poetry, Bloodaxe Books, has a summary of her career here.

Postscript: A small example of her cultural efforts on behalf of the Brodsky legacy in 2018, in The Guardian here.