Happy 100th Birthday to the Soviet Homer! “Chilling out is not exactly his thing.”

Thursday, December 13th, 2018This week’s quietest centennial belongs to Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, the writer who destroyed an empire. That’s from the New York Times, commemorating the 100th birthday of the writer who wrote The Gulag Archipelago, and died in 2008. The article is by the Russian’s biographer, Michael Scammell (we worked together briefly at Index on Censorship, which he founded, in London):

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, pundits offered a variety of reasons for its failure: economic, political, military. Few thought to add a fourth, more elusive cause: the regime’s total loss of credibility.

This hard-to-measure process had started in 1956, when Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave his so-called secret speech to party leaders, in which he denounced Josef Stalin’s purges and officially revealed the existence of the gulag prison system. Not long afterward, Boris Pasternak allowed his suppressed novel “Doctor Zhivago” to be published in the West, tearing another hole in the Iron Curtain. Then, in 1962, the literary magazine Novy Mir caused a sensation with a novella set in the gulag by an unknown author named Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn.

That novella, “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” took the country, and then the world, by storm. In crisp, clear prose, it told the story of a simple man’s day in a labor camp, where he stoically endured endless injustices. It was so incendiary that, when it appeared, many Soviet readers thought that government censorship had been abolished.

I looked for Anna Akhmatova‘s comment on Solzhenitsyn, but instead found Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky‘s remarks in the Iowa Review in 1978 (from my Joseph Brodsky: Conversations):

Q: What’s your opinion of Solzhenitsyn and the legend which has been built around him?

A: (Long pause) Well, let’s put it this way. I’m awfully proud that I’m writing in the same language that he does. I think he’s one of the greatest men ever … one of the greatest and most courageous men who has ever lived in this century. I think he is an absolutely remarkable writer. As for legend … you shouldn’t worry or care about legend, you should read the work. And what kind of legend? He has his biography … and he has his words. …

Q: Please go on.

A: He has been reproached quite a bit by various critics, by various men of letters, for being a second-rate writer, or a bad writer. I don’t think it’s just … because the people who are judging the work of literature are sort of building their judgment on the basis of systems of aesthetics which we inherited from the nineteenth century. What Solzhenitsyn is doing in literature cannot be judged by this aesthetic standard just as his subject matter cannot be judged by our ethical standards. Because when the man is talking about the annihilation or liquidation of sixty million men, there is no room, in my opinion, left to talk about literature and whether it’s a good type of literature or not. In his case, literature is absorbed in the story.

What I’m trying to say is this. Curiously enough, he is the writer, but he uses literature, and not in order to create a new aesthetics but for its ancient, original purpose: to tell the story. And in doing that, he’s unwittingly, in my opinion, expanding the framework of literature. From the beginning of his career, as far as we can trace it on the basis of his successive publications, you see quite an obvious erosion of the genres.

What we start with, historically, is a normal novella, One Day, yes? Then he goes to something bigger, Cancer Ward, yes? And then he went to something which is really neither a novel nor a chronicle but somewhere in between, The First Circle. And then we’ve got this Gulag which is, I think, a new kind of epic. It’s a very dark epic, if you wish, but it’s an epic.

I think that the Soviet rule has its Homer in the case of Solzhenitsyn. I don’t know what else to say. And forget about legends, that is real crap … about every writer.

But something I always wondered was: what was it like to actually live with a man like Solzhenitsyn. For that you have to go to David Remnick’s 1994 New Yorker profile, “The Exile Returns”:

There is something at once frenetic and peaceful about the Solzhenitsyn household. Everyone has a job to do, and everyone does it with efficiency and evident pleasure. Upstairs, Natalia has her own office, where she runs what is, in essence, a literary factory. For Solzhenitsyn’s latest works, she sets the type on an I.B.M. composing machine, and then she sends the typeset pages to Paris, where their friend Nikita Struve runs the Russian-language YMCA-Press. Struve has only to photograph the set pages, print them, and bind them. Natalia has set all twenty volumes of Solzhenitsyn’s sobranie sochineny—his collected works. Only now that Solzhenitsyn has completed his series of immense historical novels, “The Red Wheel,” is either author or amanuensis able to concentrate on the move back to Moscow.

The children—Yermolai, Ignat, and Stephan, and their older half brother, Dmitri Turin—have also been very much a part of the Solzhenitsyn enterprise. During the family’s first years in Cavendish, they began the day with a prayer for Russia to be saved from its oppressors. They went to local schools, and when they came home in the afternoon their father gave them further lessons in mathematics and the sciences (Solzhenitsyn had been a schoolteacher in Russia) and their mother tutored them in Russian language and literature. Until the boys began leaving home for boarding schools and college, they, too, helped with literary chores, setting type, compiling volumes of Russian memoirs, translating speeches. Now they are spread across the world. Dmitri lives in New York, where he restores and sells vintage motorcycles. Yermolai, after two years at Eton, went to Harvard, and while he was there he studied Chinese and had a part-time job as a bouncer at the Bow &Arrow, a Cambridge bar; he is now living in Taiwan and wants to begin working soon in China. Ignat is studying piano and conducting at the Curtis Institute of Music, in Philadelphia, and has performed around the world, to spectacular reviews, including a series of triumphant concerts with his father’s old friend Mstislav Rostropovich last September in Russia and the Baltic states. Stephan is a junior at Harvard and is majoring in urban planning.

Ignat and Stephan were home for winter vacation, and I asked them if their father ever stopped working.

Ignat smiled slyly and replied, “No, he’s never said, ‘Today I’m just gonna chill out, take a jog, and blow off this “Red Wheel” thing.’ Not one day.”

“Chilling out is not exactly his thing,” Stephan added.

“So, fine. Why can’t the West get over this?” Ignat said, growing more serious. “Why is his working all the time such an annoyance? Why is it so bad that he lives in Vermont and not the middle of Manhattan?”

“They assume he must be weird,” Stephan said.

Scammell concludes: “After his death Solzhenitsyn was given a sumptuous funeral and buried at the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow. In 2010 “The Gulag Archipelago” was made required reading in Russian high schools. Moscow’s Great Communist Street has been renamed Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Street, his centennial is being celebrated with great pomp this week in Russia, and a statue of him in Moscow is planned for the near future.

“All this would give the writer great satisfaction. But though feted and exploited by questionable allies, Solzhenitsyn should be remembered for his role as a truth-teller. He risked his all to drive a stake through the heart of Soviet communism and did more than any other single human being to undermine its credibility and bring the Soviet state to its knees.”

The New York Times piece is here. The long ago New Yorker piece here.

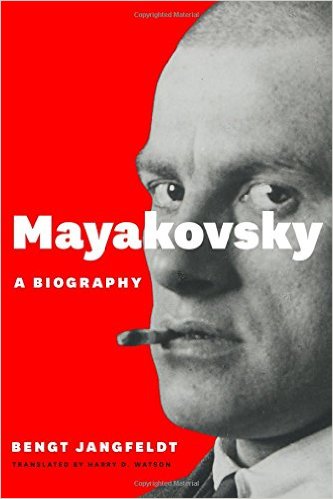

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.