“Beauty is not a luxury”: Dana Gioia on the antidotes to power

Saturday, July 21st, 2012 Dana Gioia‘s new volume of poems, Pity the Beautiful, is getting some early buzz (including a Philadelphia Inquirer review here). The poet (and former chairman of the NEA) recently sent me the latest issue of Gregory Wolfe‘s Image Journal which includes a satisfyingly long interview – even better than a review. None of it’s online, so I’ll include a few excerpts from the interview with Erika Koss. Besides, it meshes nicely with some of the Book Haven’s earlier posts, so I couldn’t resist.

Dana Gioia‘s new volume of poems, Pity the Beautiful, is getting some early buzz (including a Philadelphia Inquirer review here). The poet (and former chairman of the NEA) recently sent me the latest issue of Gregory Wolfe‘s Image Journal which includes a satisfyingly long interview – even better than a review. None of it’s online, so I’ll include a few excerpts from the interview with Erika Koss. Besides, it meshes nicely with some of the Book Haven’s earlier posts, so I couldn’t resist.

The Book Haven was pleased to include his long poem “Special Treatments Ward” in its entirety, in an earlier post here. Here’s what he said about the poem in the new interview:

The Book Haven was pleased to include his long poem “Special Treatments Ward” in its entirety, in an earlier post here. Here’s what he said about the poem in the new interview:

“This was the most difficult poem I’ve ever written. It began when my second son had a serious injury that required an extended stay in a children’s neurological ward where nearly every other child was dying of a brain or spinal tumor. Having lost my first son, I was entirely vulnerable to the pain and confusion of the sick children and their desperate parents. I began to write a poem about how unprepared everyone in the ward was for what they had to face. But the poem kept growing and changing. It took me sixteen years to finish. I didn’t want to finish it. I wanted to forget it, but the poem demanded to be finished. So the poem is not simply about my first son or my second son, though they are both mentioned. It is about the children who died.”

We also had a post describing “Haunted,” Dana’s ghost story – it’s here. From the interview:

“Actually, this poem began with the first two lines:'”I don’t believe in ghosts,” he said. “Such nonsense./But years ago I actually saw one.”‘ As soon as I heard those two lines, the whole poem started to unfold, though it took an immense amount of work to create the narrative tone and the musical qualities I wanted. The odd thing about poems is that when the good ones come we often realize that we have been writing them in the back of our mind for years. A single line brings them into existence almost fully formed.”

‘Haunted’ is a ghost story that turns into a love story about a mutually destructive couple, but then at the end the reader realizes that the whole tale was really about something else entirely. The real theme is quite the opposite of what it initially seems. I wanted the poem to have the narrative drive of a great short story but also rise to moments of intense lyricality …”

He lists among the influential philosophers of his life Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Miguel de Unamuno, Mircea Eliade, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, George Orwell, Marshall McLuhan, Jacques Maritain, and recently René Girard. What odd bedfellows that crew would be.

But who was the most important philosopher of all? Surprise.

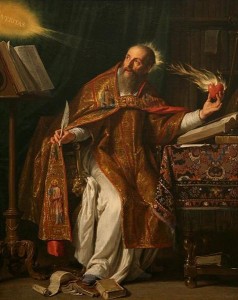

“One book that has exercised a lifelong influence on me is Saint Augustine‘s City of God, which I first read as a Stanford undergraduate. It has probably shaped my adult life more than any other book except the Gospels. Augustine helped me understand the danger of letting the institutions of power – be they business, government, or academia – in which we spend our daily lives shape our values. We need to understand what it is we give to the City of Man and what we do not. I couldn’t have survived my years in business as a writer had I not resisted the hunger for wealth, power, and status that pervades the world. The same was true for my years in power-mad Washington. Another writer who helped me understand these things was the Marxist philosopher and literary critic Georg Lukács – not a name one usually sees linked with Augustine’s, but he was another compelling analyst of the intellectual and moral corruptions of institutional power.”

Here’s a kind of egalitarianism that goes well beyond Marx: “Beauty is not a luxury,” he insists. “It is humanity’s natural response to the splendor and mystery of creation. To assume that some group doesn’t need beauty is to deny their humanity.”