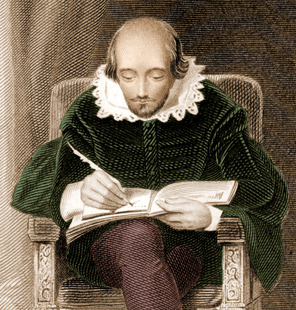

Stanford Repertory Theater performs Noël Coward’s Hay Fever – but who was the real Judith Bliss?

Monday, July 20th, 2015

The Bliss Family: David (Bruce Carlton), Judith (Courtney Walsh), Sorel (Kiki Bagger) and Simon (Austin Caldwell).

Playwright and songwriter Noël Coward spent a single weekend in the home of actress Laurette Taylor and her husband, the playwright J. Hartley Manners. The visit was such that he later, in three feverish days, wrote the play for which he is arguably best known, Hay Fever. Taylor made a big target: her larger-than-life personality was renowned, along with her theatrical moods and eccentricities. She was the sort of person who, we would say today, sucked all the oxygen out of the room. The play was a hit from the moment it opened in 1925. There were casualties, however. To put it mildly, Hay Fever strained the friendship.

Ungrateful guest.

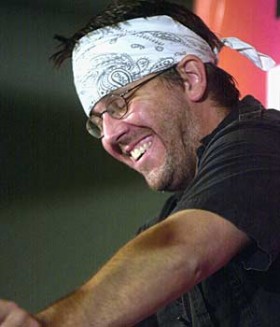

The Stanford Summer Repertory production, which opened last weekend, continues through August 9, with Courtney Walsh as Judith Bliss, Kiki Bagger as Sorel Bliss, Richard Carlton as David Bliss, Rush Rehm as Richard Greatham, Catherine Luedtke as Clara, Austen Caldwell as so-so novelist Simon Bliss, all under the direction of Lynne Soffer – tickets and info here. You can’t really call a family dysfunctional when they’re so pleased with themselves, can you? The Bliss family likes itself, even if no one else does.

The play has been described as a cross between outright farce and comedy of manners. Stanford weighs in for the former, sometimes to its detriment. I could have used a slower pacing in the opening scenes, to hear the dialogue more clearly and get a feel for the characters before the comedy builds its own momentum. Sometimes the performers don’t seem to be actually listening to each other, or minding the cigarettes they light up and stub out every few minutes.

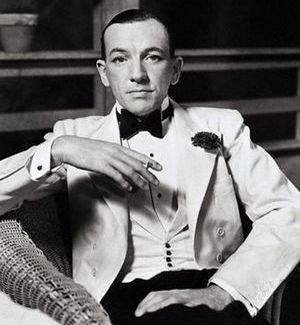

Judith Bliss is not just living in her past but the past, a different era of theater altogether. Perhaps a modern audience wouldn’t have understood the distinction, but it’s part of the fun of the play. The central character, matriarch Judith Bliss, is an actress who is past her heyday, hungering for a smashing comeback and longing for the return of melodrama with its clichéd gestures and formulaic plots. That era had given way with an excited crash to the brazen sexuality of the jazz baby. (Remember 1925 was the magic year of both Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and The Great Gatsby.)

She really did make a comeback.

This production builds heat as it moves, trust me (and kudos to costume designer Connie Strayer). Two characters to watch in this production: Berkeley Rep veteran Deborah Fink excels as vamp flapper Myra Arundel. She’s sleek, smug, and self-contained as a cat, and doesn’t begin to unravel until the very last scenes. Another scene stealer: Kathleen Kelso as ingenue flapper Jackie Coryton. She’s making her Stanford Repertory Theater debut. The tall, willowy blonde sways uncertainly like a tall narrow tree in a high wind. The face under the cloche hat is constantly on the verge of crumpling into tears. She’s already unraveled, the moment she steps into the country house.

The original Judith Bliss, Laurette Taylor, was an actress from a previous era, more of the generation of Mary Pickford than Anita Loos or Clara Bow. Was Laurette Taylor the has-been that Noël Coward immortalized? Not quite. She finally did make her comeback in 1946, but not in the revival of a cheesy melodrama. She was the original Amanda Wingfield in an unforgettable performance of The Glass Menagerie. Tennessee Williams’s “sad, delicate drama of a struggling family in extremis was greeted with modified rapture by most of the critics as a new voice, a potential turning point for a tired commercial theatre,” according to Robert Gottlieb in The New Yorker (here):

But the true rapture was reserved for the play’s star, Laurette Taylor, reappearing after a difficult interlude of alcoholism, but still a revered name in the theatre. Her biggest success, decades earlier, had been in the comedy Peg O’ My Heart, which she performed for years both in New York and around the country, and in a movie adaptation. Now, as Amanda Wingfield, first in Chicago and then on Broadway, she emerged as an actress without peer, her performance referred to again and again as the greatest ever by an American actor. When I saw her, I knew it was the finest acting I had ever seen, and, more than sixty-five years later, I still feel that way. But why? What did she do that made her acting so unforgettable?

She simply didn’t act. Or so it appeared. She wasn’t an actress; she was a tired, silly, irritating, touching, fraught, aging woman with no self-awareness, no censor for her ceaseless flow of words, no sense of the effect she was having on her children—or the audience. It was as if you were listening in on the stream of her consciousness. Her self-pitying yet valiant voice, reflecting both the desperation of her situation and the faded remnants of her Southern-belle charm, was maddening, yet somehow endearing. You wanted to hug her, to swat her, to run from her—in other words, you reacted to her just the way her son, Tom, did.

Actress Patricia Neal called it “the greatest performance I have ever seen in all my life.” Sometimes there really are happy endings. Even for drama queens.

Dysfunctional family? Maybe not. Richard Carlton, Courtney Walsh, and Kiki Bagger in “Hay Fever.”