A luftmensch in search of the perfect conversation: NYPL’s “curator of public curiosity”

Saturday, March 10th, 2018

A fellow luftmensch: Paul Holdengräber at NYPL

I have met amazing people on Twitter, and one of my golden finds was Paul Holdengräber. We both love literature, but we have something more in common: we’re both luftmenschen.

At work. (Photo: Jori Klein/NYPL)

“There’s a Yiddish word for someone who may not be terribly grounded,” he says. “It’s a beautiful word: luftmensch. It means someone who has his feet firmly planted—in midair. There’s something of an untethered balloon in me.” It beats Merriam-Webster’s definition: “an impractical contemplative person having no definite business or income.” Not true. I have a definite “business” of sorts: I’m a writer, a journalist, a blogger, an author. And Paul? He’s the director of public programs for the New York Public Library. He founded LIVE from the NYPL, and organized its literary conversations. Since February 2012, he has hosted The Paul Holdengräber Show on the Intelligent Channel on YouTube.

“‘I’m the curator of public curiosity.’ I’m the midwife,” he told Will Corwin at Art Papers last year. “When you are in the audience, you are hopefully an interested listener. In some ways, you want to be in my seat—or maybe you don’t want to be in my seat, but you imagine what you would have asked. But my goal—as I did with David Lynch, Ed Ruscha, JAY-Z, Zadie Smith, Patti Smith, or Philip Glass—is to represent the audience as best as I can, their interests and curiosities. The question that I’m trying to phrase is—I’m hoping—the question that the audience as a whole, and some people in particular, may have.”

Once-a-year sanity. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

A regular guest of his conversations is Werner Herzog. “I speak to him at least once a year to remain sane,” he says.

He has a reason for being a luftmensch. He was born in Texas and has an American passport. His parents, however, were Austrian Jews fleeing Vienna and the Nazis. They did so via Haiti, which had no immigration quota for Jews, and then Mexico, where his sister was born. When his mother was having a problem pregnancy, his father, a former medical student who had become a farmer in the New World, whisked his wife to Houston, where the best hospitals were located. Voilà! Paul was born an American citizen. And then the family moved to Brussels.

Paul studied philosophy at the Université Catholique de Louvain and the Sorbonne. The connection of philosophy with his his current line-of-work is obvious:

Tzara in 1923

“Yes, I believe deeply that we come to thought through words—thought is made in the mouth, or some such sentence from Tristan Tzara. Philosophy, as we believe it to be, started with a conversation. I don’t particularly think about how it will play itself out when written down. I think there’s such a difference between the written word and the spoken word. Some people speak in paragraphs; I don’t know what I speak in— I suppose my claim to a profession is to make other people speak, to find a way of giving them words and to find a way of bringing about a thought. I feel that through speaking we can discover ourselves. Not dissimilar is the word autobiography: auto-bio-graphein. It literally means “the life coming-to-be through its writing”; so, the self coming to life through writing and discovering itself through writing. Some people discover themselves through writing, if we consider literary history, from Rousseau to other great people who wrote autobiographies.”

His mother was fourteen when she left Vienna, “so she had seen enough to know it was terrible and to never, ever talk about it. But she transmitted the trauma. When the Austrian government, through the Austrian president, awarded me with the Austrian Cross of Honor for Art and Science—a funny thing to give a cross to a Jewish boy—I said to my mother, ‘I don’t think I should accept.’ She said, very firmly, ‘Be gracious, don’t mention the unpleasantness, and my story is not yours.’ Which is quite something.”

“Memories I don’t have…”

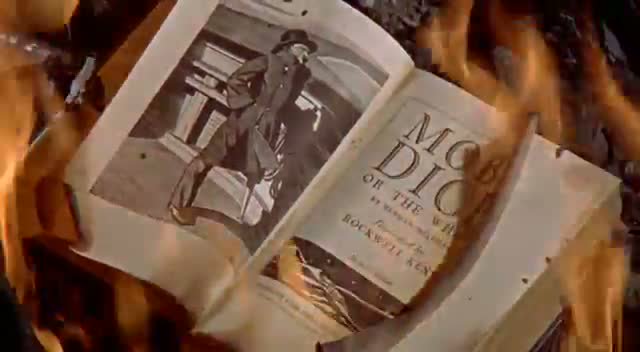

“My trauma is a secondhand wound; it’s a transmission of trauma. The [words] transmission and tradition are the same in Hebrew: they [translate to] “what is passed on.” So I’m living with the memory of something I never experienced, the memory of something I don’t know. I was inspired by Nathalie Zadje, a psychoanalyst who studied transmission of trauma from the point of view of certain émigré cultures, particularly in North Africa, and how different that transmission is in different cultures. She studied how trauma passes from one generation to the next. But I grew up very obsessed with the Holocaust, very obsessed with my parents’ history, maybe in a way that was unhealthy. I do think that my interest in Edmund du Waal, Werner Herzog, Anselm Kiefer, and Claude Lanzman all comes from the way in which the world was transformed, changed, and to some extent destroyed. When Jonathan Demme invited me to speak to him about Fahrenheit 451, both the Truffaut movie and the Ray Bradbury story, the burning of the books brought back memories that I don’t have.

His goal in life? “As I think of it, I’m after the perfect conversation. I’m after the Platonic idea of what the best possible conversation could be, and therefore it eludes me like a collector who would hope in some way never to have the last piece in his collection. If he did, then it would be the death of the collector.”

Read the whole conversation here.

Author and performer Patti Smith and I don’t have much in common, except for two mutual friends –

Author and performer Patti Smith and I don’t have much in common, except for two mutual friends –