Rilke’s last days: “…that someone, somewhere, in France or England, knows me, is translating me, mentions me…”

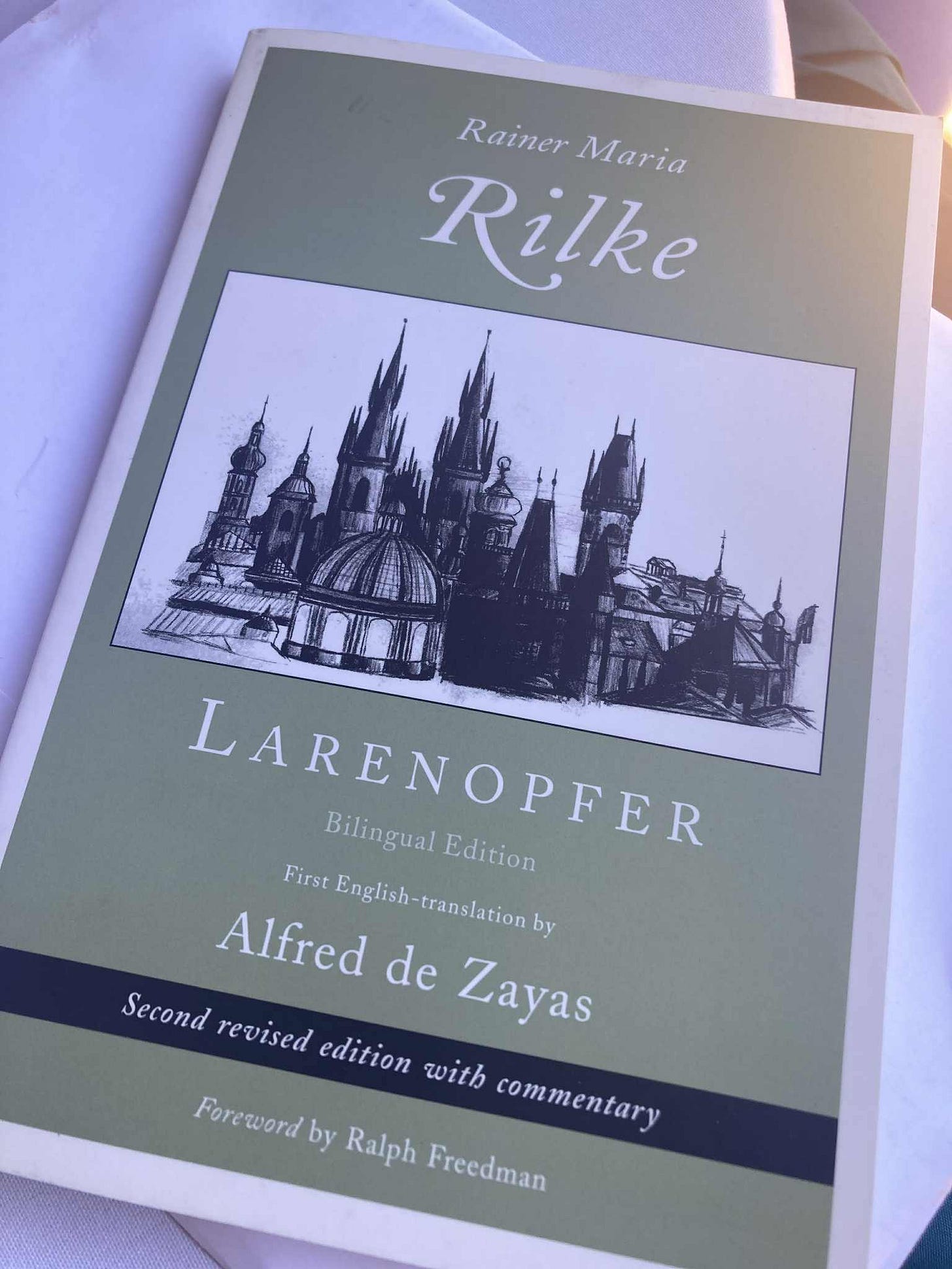

Thursday, August 14th, 2025Archivist extraordinaire Elena S. Danielson (at right) kindly took me out to the Stanford Faculty Club for lunch last week. The kindness didn’t stop with the tiramisu. The former director of the Hoover Library & Archives also gave me a new edition of Rainer Maria Rilke‘s “Larenopfer” – to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the poet’s birth. The volume includes ninety of Rilke’s early poems from turn-of-the-century Prague, in German and English. Another treat, a copy of a 1926 letter from Rilke to Leonid Pasternak, the Russian poet’s father, an eminent painter.

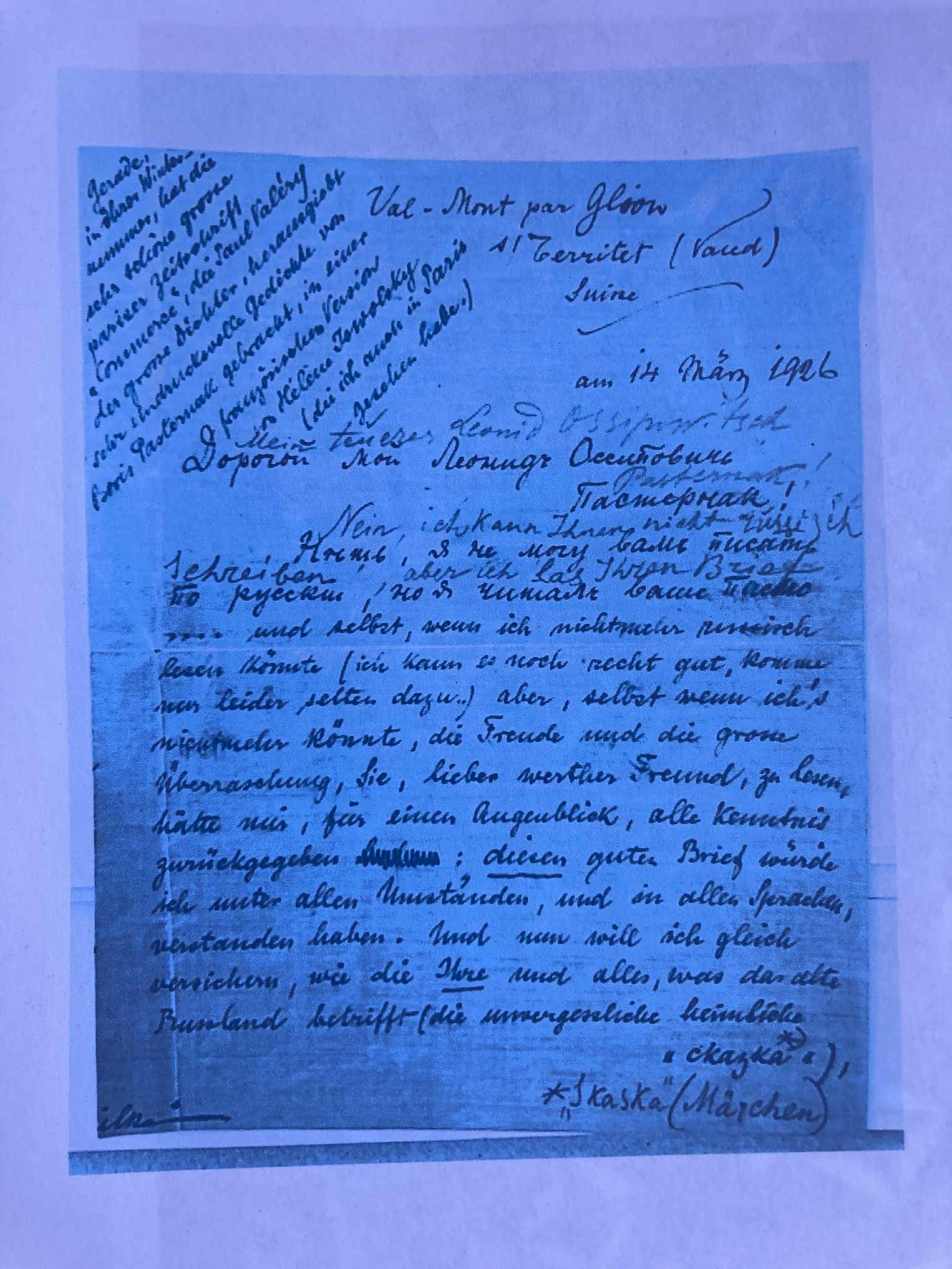

In the letter dated March 14, 1926, the celebrated poet, already seriously suffering from the fatal illness that would end his life nine months later, wrote a lengthy, detailed, and graciously cordial letter to a Russian artist living in Berlin, Leonid Pasternak (1862-1945), the father of poet and novelist Boris Pasternak, who remained at that time in Moscow. Despite premature rumors of Rilke’s death, news reached Leonid that he was still alive, though ill, and celebrating his 50th birthday. Elated by the good news, the artist sent the great writer a birthday greeting by way of his publisher, since he didn’t have Rilke’s mailing address.

Rilke responded as soon as the letter finally reached him at the isolated medieval stone tower where he was writing his final masterpieces in an obscure corner of Switzerland. He starts out in Russian, which they had once used for their correspondence, but he switches quickly to German as his Russian skills had faded; he knew Pasternak, originally from multicultural Odessa, was fluent in German. (On the original paper, someone, possibly a family member, lightly penciled in a translation of the brief Russian phrases into German.) Rilke goes on to emphasize his continuing love of Russian culture and his faith that it will be restored, despite the chaos cause by war and revolution. And he renews their ties of friendship.

Before the Great War, Leonid had met the then unknown poet, just in his mid-twenties in Moscow in 1899, and once again by chance at a train station with the artist’s 10-year-old son Boris in 1900. A couple more brief encounters in Italy in 1904 and a few letters. That is all.

And yet they both remembered each other with great fondness. Both had a talent for lasting intellectual friendships. In his memoirs Leonid writes of the 1899 meeting: “Before me in my studio stood a young, very young, delicate, blond foreigner in a Loden coat … And already after the first short conversation we were like good old friends (which we later became).” (Die Familie Pasternak: Erinnerungen, Bericht, Geneva: Éditions Poésie Vivante, 1975, p. 62) The cordial feelings lasted even though they had no contact during the turbulent war years.

The 1926 letter in question – the first page shown here – had been published in German, but the original artifact with its still elegant handwriting, despite serious illness, conveys far more meaning than the copy in cold print. The Pasternak family carefully preserved this artifact for many years through the trauma of war, relocation, and exile. It was treated as something of a holy relic for the family. Starting in 1996, the Pasternak family began donating family papers to the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University for safekeeping. Among the many treasures in the collection is this original letter. In the published version, there is a brief postscript printed at the end. The original document shows this added afterthought displayed prominently in the upper left-hand corner of the first page. This brief note, crammed at the top, was even more important than either the writer Rilke or the recipient Leonid Pasternak realized at the time:

Gerade in ihrer Winter-nummer, hat die sehr schöne grosse pariser Zeitschrift “Commerce”, die Paul Valéry der grosse Dichter herausgibt sehr eindrucksvolle Gedichte von Boris Pasternak gebracht, in einer französischen Version von Hélène Iswolsky (die ich auch in Paris gesehen habe.)

Here is a translation of the note: “Just now, in its winter issue, the very beautiful, big Paris journal, Commerce, that Paul Valéry, the great poet publishes, are very impressive poems from Boris Pasternak, in a French translation by Hélène Iswolsky (whom I also saw in Paris).”

The full significance of the letter, especially the note in the corner, was not well understood in the English-speaking world until Nicolas Pasternak Slater translated and published the family correspondence in 2010. (Boris Pasternak: Family Correspondence 1921-1960, translated by Nicolas Pasternak Slater, Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2010. Reviewed in The Book Haven in 2011 here.) Leonid did not forward the original letter from Berlin to Boris in Moscow – he feared it might be lost – so he gave it to his daughter Josephine, who was also in Germany. Boris had previously written in August 1925 that he was devastated when he heard (erroneously as it turns out), that Rilke had already died.

When Boris learned about the letter from Rilke to his father, and got the news that Rilke was not only still alive and but had actually mentioned his poetry in the March 14, 1926 letter, Boris wrote to his sister from Moscow: “Our parents told me about Rilke’s letter, which has so thrown me that I haven’t been able to work today. What excited me wasn’t what probably pleased Papa and Mama, since after all I only got to hear of it by ricochet—that someone, somewhere, in France or England, knows me, is translating me, mentions me—but naturally I haven’t seen any of this with my own eyes…you need to know what Rilke was for me, and when this all started. This news was a short-circuit between widely separated extremes of my life. The incongruity of it shattered and devastated me, and now I don’t know what to do with myself.

Boris had told his sister that he had been dreaming, in fact quite unrealistically, of visiting Rilke – whom he had briefly encountered as a child 26 years earlier – in the poet’s medieval Swiss tower. At this point Boris was just trying to survive in Moscow after the devastations of the Great War and the catastrophic conditions precipitated by the Russian Revolution and Civil War while his father, mother, and sisters enjoyed the temporary safety of Germany. They would later be forced to leave Germany for England.

On top of everything else, you need to know who Valéry is—assuming this really is Paul Valéry, which is totally unlikely!” (Correspondence p. 43.)

(At right: the poet Rilke, painted by Leonid Pasternak)

Once Boris Pasternak in Moscow knew that Rilke was still alive, he and his dear friend, the poet Marina Tvetaeva, living in France, began a brief but passionately poetic three way-epistolary romance with Rilke in Sierre, Switzerland just before Rilke died. Rilke wrote something on the order of 17,000 letters in his lifetime, corresponding right up to the end of his life December 29, 1926. (The exact number of letters is not knowable, but it is certainly more than 10,000.) Of this remarkable correspondence, the last letters with Rilke in Sierre, Switzerland, Tsvetaeva in Paris, and Boris Pasternak in Moscow are among the most lyrical and most beautiful. And this remarkable exchange was initiated by the March 14, 1926 letter in question.

More on the two photos: “Rilke (1875-1926) in Moscow,” by Leonid Pasternk, an oil painting made in 1928, so a posthumous portrait based on earlier sketches depicting Rilke as a young man when he visited Moscow, prior to World War I, as an unknown poet. Apparently painted in Berlin some two decades later, the portrait is now in the Pinakothek Museum in Munich. A version in pastels is preserved at the Ashmolean in Oxford, in the UK where many family members live today.

Whoever looks seriously will find that neither for death, which is difficult, nor for difficult love has any clarification, any solution, any hint of a path been perceived; and for both these tasks, which we carry wrapped up and hand on without opening, there is no general, agreed-upon rule that can be discovered. But in the same measure in which we begin to test life as individuals, these great things will come to meet us, the individuals, with greater intimacy. The claims that the difficult work of love makes upon our development are greater than life, and we, as beginners, are not equal to them. But if we nevertheless endure and take this love upon us as a burden and apprenticeship, instead of losing ourselves in the whole easy and frivolous game behind which people have hidden from the most solemn solemnity of their being, – then a small advance and a lightening will perhaps be perceptible to those who come long after us. That would be much.

Whoever looks seriously will find that neither for death, which is difficult, nor for difficult love has any clarification, any solution, any hint of a path been perceived; and for both these tasks, which we carry wrapped up and hand on without opening, there is no general, agreed-upon rule that can be discovered. But in the same measure in which we begin to test life as individuals, these great things will come to meet us, the individuals, with greater intimacy. The claims that the difficult work of love makes upon our development are greater than life, and we, as beginners, are not equal to them. But if we nevertheless endure and take this love upon us as a burden and apprenticeship, instead of losing ourselves in the whole easy and frivolous game behind which people have hidden from the most solemn solemnity of their being, – then a small advance and a lightening will perhaps be perceptible to those who come long after us. That would be much.

Which brings me to

Which brings me to

Every time I hear the first schoolyard rhyme, I remember the version I heard in India, where the children sing:

Every time I hear the first schoolyard rhyme, I remember the version I heard in India, where the children sing: