A night at the opera with Andy Ross – actually, four nights, because it’s Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

Sunday, June 17th, 2018“I’ll be at Das Rheingold tonight at the San Francisco Opera,” Andy Ross told us. He’s a literary agent and former proprietor of Cody’s Books in Berkeley. We’ve written about his face-off with a fatwa here, but now he’s facing another battle: the San Francisco’s Wagner fest, which continues into July (read about it here). Andy is a longtime fan of Richard Wagner’s corpus: “I discovered it in college. Most people liked the Beatles. I liked Wagner. People thought I was weird.” Now there’s no turning back.

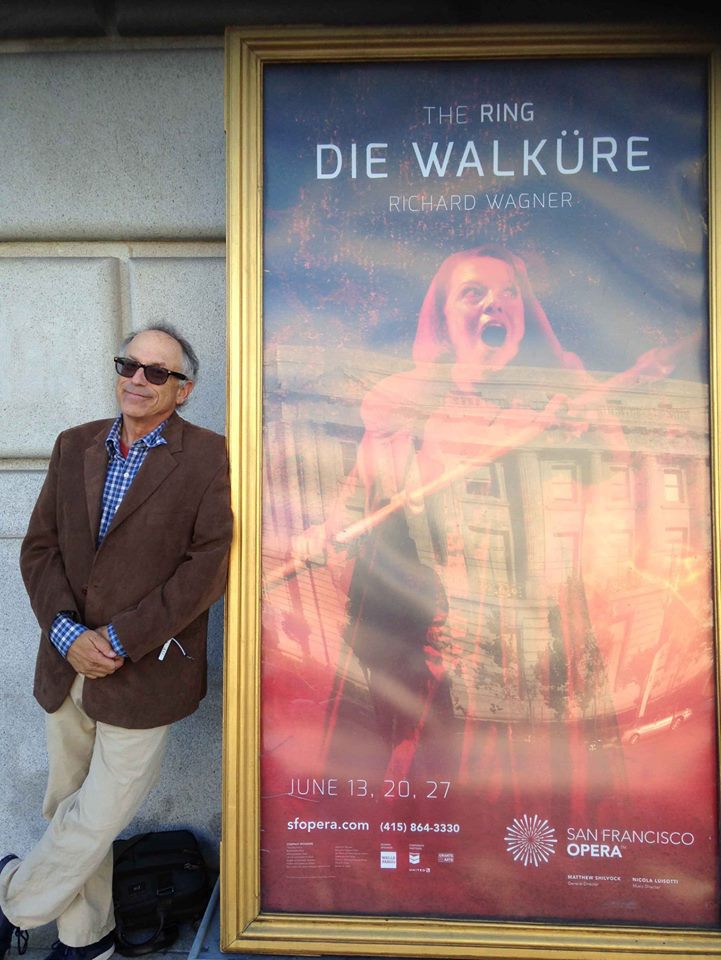

“I’ve got my spear and horned helmet and I’m ready to go.” Let’s go with him. Here he is on the first night.

“Just got back from Das Rheingold. It was great.”

Night 2: At Die Walküre last night. My favorite Ring opera. Magnificent performances by the artists and the orchestra. It even managed to distract me from the weird post-modern staging. (Although I have to admit to a certain admiration in the third act with the Valkyries dropping onto the stage from parachutes looking like Amelia Earhart).

Walküre is the most human of all the Ring operas. The Ring is myth, and the characters sometimes become more symbolic of universal qualities than than flesh and blood human beings. Moreover, Wagner’s tendency to overlay the story with Schopenhauerian philosophical musings means that the opera doesn’t always find its way to the heart. But not so in Walküre. The first act is, in my mind, the greatest love scene in all of opera, from the glimmering recognition of Siegmund and Sieglinde to the climactic moment when Siegmund pulls Wotan’s sword from the tree as Sieglinde looks on in ecstasy. Its emotionality is amplified by the vulnerability of the characters and the knowledge of their impending doom. In the following acts, the immortals, Brunnhilde and Wotan, find their own humanity – literally for Brunnhilde, who, in the heartbreaking final scene of the opera, is banished from Valhalla, deprived of her immortality, and laid to rest by Wotan, who surrounds her with the magic fire that can only be penetrated by a hero who is without fear. Not a dry eye in the house.

Night 3: Last night, David Ross and I saw Siegfried, the third opera of Wagner’s Ring. Siegfried has always seemed to me the Ring’s problem child. I find the music and the drama in the first two acts disappointing. The biggest disappointment is the character, Siegfried. That’s a problem because he is on stage for most of the four hours of the opera. Wagner’s hero seems more like a cross between a boy scout and the lug who played JV guard in high school. Moreover, Wotan comes on stage very early on, always a sign that maybe it’s time to go out to the lobby and check your email. True to form, he goes on a long unmusical backstory exposition. The second act is just plain boring. The music is thin and unmemorable. The shimmering “forest murmurs” sound a little like mediocre Debussy. Even Fafner, the dragon, is something of a bore. I’ve always felt Wagner had simply run out of steam by Act 2 of Siegfried. He had lost his mojo.

Then the orchestra begins the prelude to Act 3, and something miraculous happens. To backtrack a little, Wagner put down the score to The Ring after composing Act 2 and didn’t go back to it for a decade. During that time, he composed his two great mature masterpieces, Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg. When he returned to Siegfried, you see the transformation right away. The orchestra, always Wagner’s strong suit, is fuller, richer, deeper, more complex. The music is powerful and evocative. Even Wotan, who makes his final appearance in The Ring, has compelling music. And nothing quite prepares us for the electrifying and triumphant love duet that ends the opera. Wagner composed three great love scenes: the second act duet of Tristan, Siegmund and Sieglinde’s duet in Act 1 of Walküre, and this final scene of Siegfried’s awakening of Brunnhilde. This love duet lacks the eroticism of Tristan, and the heartbreaking tragic quality of Walküre. It isn’t even particularly romantic. But it puts forth a kind of heroic, triumphant message that love will change the world. It was a thrilling end that brought the entire house to its feet. There’s really only one other ending in opera packing that kind of titanic power. We’ll be hearing it on Sunday.

David Ross and I spent the last six hours seeing the final opera of Wagner’s Ring. Götterdämmerung isn’t the most popular opera in the Ring. That would be Die Walküre with its heartfelt humanity. Götterdämmerung‘s characters do not engage the listener in the same way. The music is relentlessly dark and foreboding. But this is the opera that best expresses Wagner’s musical vision of a completely integrated work of art. If you were able to ask Wagner what his most perfect work was, I have no doubt he would say it is Götterdämmerung. More than in any of the preceding operas, the orchestra dominates the story to the point where it becomes the most prominent voice. This is best seen in the incomparably glorious final scene, Brunnhilde’s immolation.

Wagner’s place in the pantheon of great composers is permanently established. But he stands apart, not because of his greatness, but because of his flaws. One would be hard-pressed to identify a flaw in any of Mozart‘s work. They are perfect. Wagner’s works are all flawed masterpieces. But he maintains his place because of the splendor of his greatest moments. The Ring, flawed though it is, is perhaps the most monumental work in Western Art. I suppose you could include Dante‘s Divine Comedy, and maybe Michelangelo‘s Sistine Chapel with that. And after seeing the complete Ring, one must admit that the music has done what was seemingly impossible, living up to the grandiosity of Wagner’s vision. Seeing it was special. We are glad we went.

And we’re glad we went with him. Read more about the San Francisco Opera’s Wagner festival, which continues into July, here.