Robert Conquest a British poet? Not so fast… he had American roots, too.

Wednesday, November 18th, 2020

Conquest at work (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

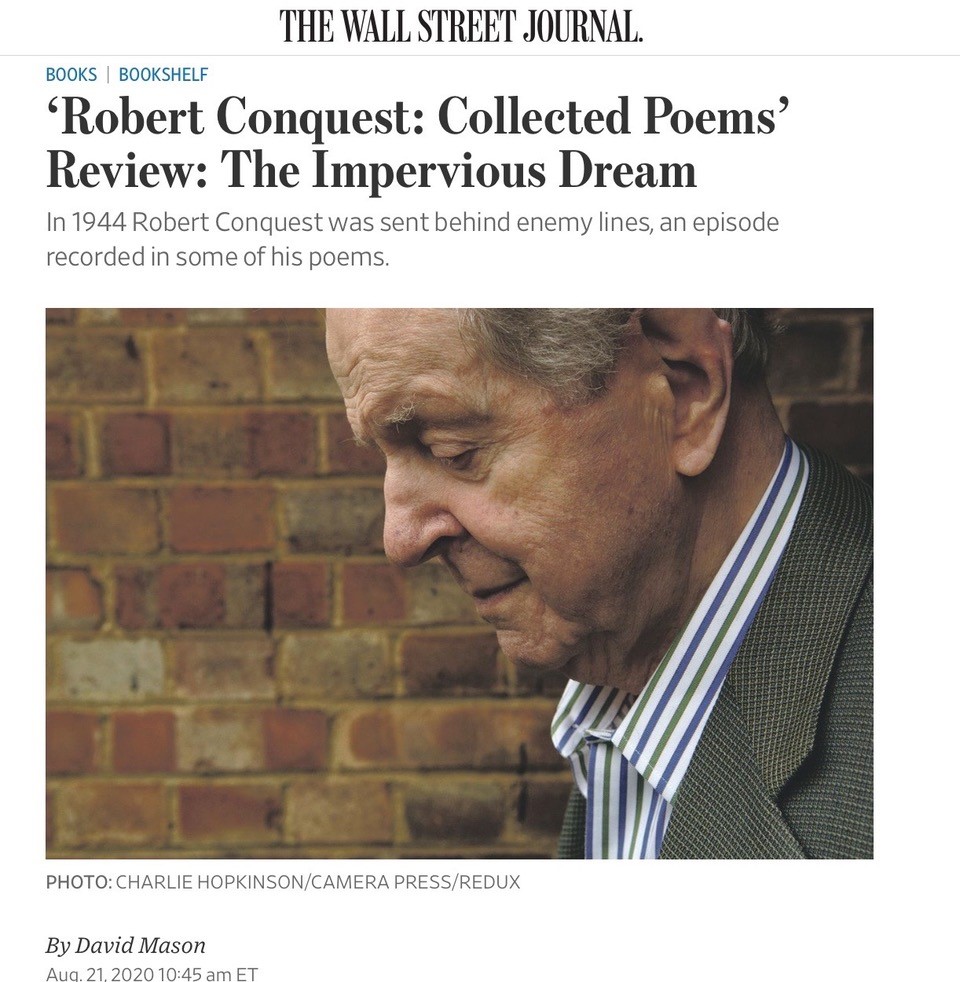

“Nothing human is alien to Conquest, who died in 2015 at age 98,” writes the inestimable Patrick Kurp in the Los Angeles Review of Books, describing the poet and Soviet historian Robert Conquest. Then Patrick makes a rare misstep when he states: “Let’s remember that he was English by birth but American by choice.”

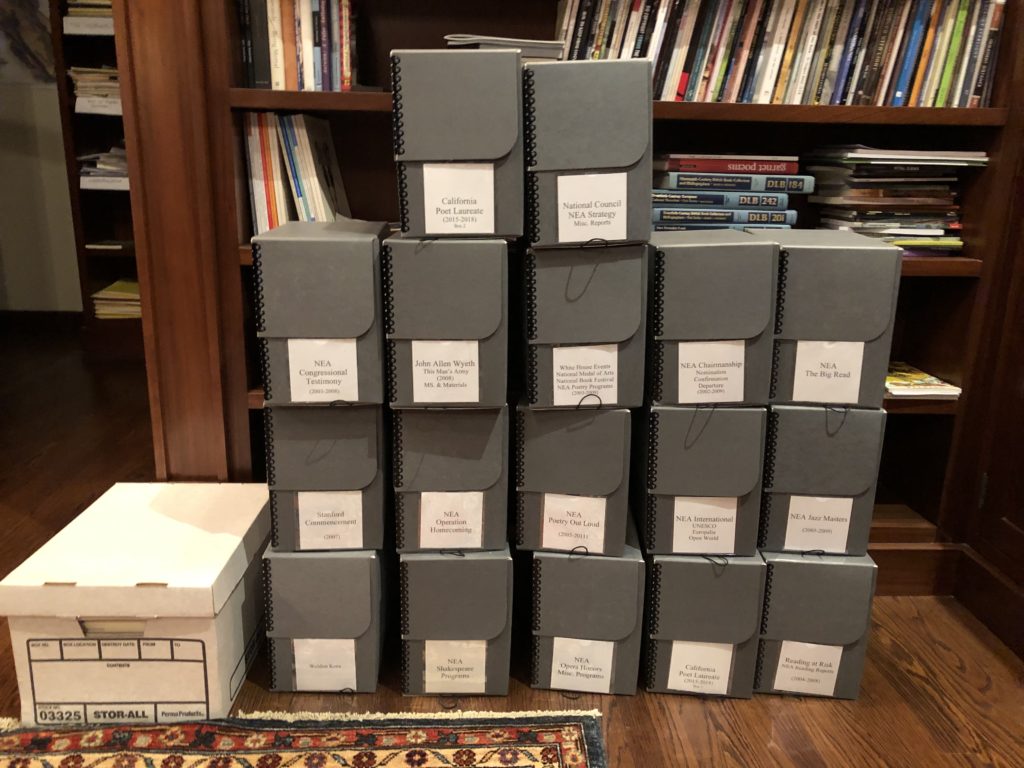

Actually, Conquest was not only American by choice – his father, Robert Folger Wescott Conquest, was American, a Virginian – so the long residence at Stanford’s Hoover Institution was something of a homecoming for his British-born son Robert Conquest, who also spent some time in Virginia as a child. [Note: Not so fast – the record on Virginia is corrected in a postscript below.] His American roots were further reinforced by his long happy marriage with an American wife, Elizabeth Conquest, who is the editor of his Collected Poems and soon a volume of letters.

He had a poetic homecoming, too, in what Patrick Kurp calls “One of Conquest’s richest, most satisfying poems.”

An excerpt from the article:

“The Idea of Virginia,” 34 four-line stanzas that encapsulate the history of the state and, by implication, the United States. “It lay in the minds of poets,” the poem begins, which Conquest characteristically clarifies: “But the land was also real: rivers, meads, mountains.” Conquest has no pretensions to being a nature poet, but he starts with an Edenic natural world: “Deer and pumas ranged its high plains. Beavers / Toiled in its streams. Bluebird and mocking-bird, / Blue jay, redbird and quail filled branches and air.” He retells the familiar story of John Smith, Powhatan, and Pocahontas without pontificating. The idea of Virginia grows naturally out of English thought:

Haydn, prose, elections, deism, architecture,

Bred the leaders of battle, governance, law.

Washington, Marshall, Madison, Jefferson, Henry

Defended a heightened England from an England lapsed.

He is at home in the world, as poets seldom are. He writes poems for intelligent readers who enjoy formal verse and humor that ranges from the ribald to the wittily rarefied, and who share his interest in particulars. Conquest will be remembered principally as the man who, even before Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, exposed the Soviet Union as a murderous tyranny in such volumes as The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties (1968) and The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (1986). Politics and history, of course, show up with some regularity in his poetry, often in a form that resembles light verse. Here is a stanza from “Garland for a Propagandist”:

He is at home in the world, as poets seldom are. He writes poems for intelligent readers who enjoy formal verse and humor that ranges from the ribald to the wittily rarefied, and who share his interest in particulars. Conquest will be remembered principally as the man who, even before Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, exposed the Soviet Union as a murderous tyranny in such volumes as The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties (1968) and The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (1986). Politics and history, of course, show up with some regularity in his poetry, often in a form that resembles light verse. Here is a stanza from “Garland for a Propagandist”:

When Yezhov got it in the neck

(In highly literal fashion)

Beria came at Stalin’s beck

To lay a lesser lash on;

I swore our labour camps were few,

And places folk grew fat in;

I guessed that Trotsky died of flu

And colic raged at Katyn.

When Conquest reviewed the 1974 appearance in English of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago (1973), he judged it “a truly exceptional work: for in it literature transcends history, without distorting it.” Conquest does something similar.

Another excerpt:

Patrick Kurp

One of the pleasures of his verse is its range of form and subject. Some poets harvest a very narrow field, too often the fenced-in self. Conquest’s poems resemble the late Turner Cassity’s in their appetite for the world and all it contains, pleasurable and otherwise, and in their satirical bite. His poems know things. In 1956, Conquest edited the influential poetry anthology New Lines, informally aligning the poets who came to be called The Movement: Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis, D. J. Enright, Thom Gunn, Elizabeth Jennings, and himself. In his introduction, Conquest dismisses the “diffuse and sentimental verbiage or hollow technical pirouettes” of the era’s “New Apocalypse” poets in the United Kingdom, such as J. F. Hendry and Vernon Watkins, and endorses a “refusal to abandon a rational structure.” In “Whenever,” Conquest endorses Wyndham Lewis’s call for “a tongue that naked goes / Without more fuss than Dryden’s or Defoe’s.”

Read the whole article here.

Postscript on April 12 from Elizabeth Conquest:

In point of fact, Bob did not spend time in Virginia as a child. In Two Muses [the poet’s unpublished memoir], he makes this point:

Treated as a normal F.O. member, in 1950 I was sent—as First Secretary—to the UK delegation to the United Nations in New York, attending the minuscule meetings of the Security Council, and the vast swarm of the General Assembly. This was my first trip to America. I was there only a month or two. But I managed to go down for a weekend with my cousin Pleasanton Conquest and his wife Julie in Baltimore—and for a few hours round Washington, including a walk across the Arlington Bridge to stand for the first time on Virginian soil.

All the same, he and his sisters felt themselves to be Virginian:

We (my parents, my two sisters—Charmian and Lutie—and I) lived in England and France over my childhood. We had American passports and always thought of ourselves as American, though in most ways completely Anglicised.

Not that we thought of it, let alone spoke of it much, but we children were very taken with our Virginian origin. To us it sounded—and felt—not more aristocratic or anything like that, but somehow all the same superior and exotic. The only effects of this were inheriting the feeling ‘give-me-the-luxuries-and-I’ll-do-without-the-necessities’, early immersion in ragtime, etc. My father was not, on the whole, interested in the Virginian side of things—born there, but his upbringing in France and later education in Pennsylvania having been entirely from the Westcott side. We had no contact with our Virginian relatives until my mother started writing to my great aunt Margaret—I suppose in the 1930s—after which they’d come over to Europe and vice versa.