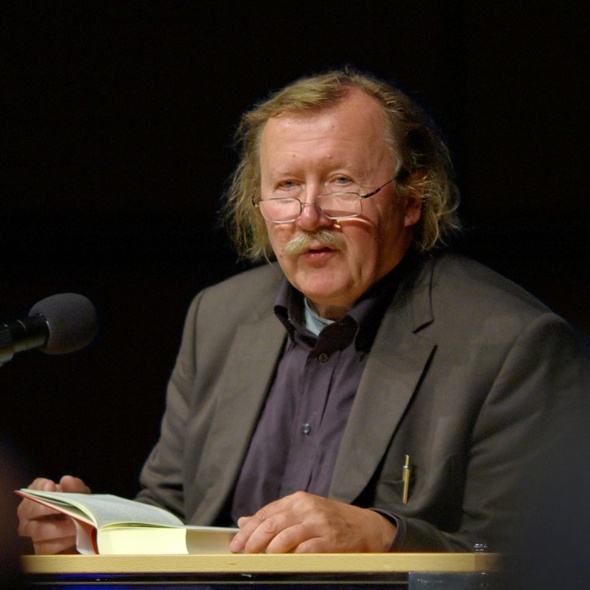

Robert Harrison with René Girard outside the Stanford Faculty Club (Photo: Ewa Domańska)

Here’s some good news for the holidays! My Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard has been named one of the San Francisco Chronicle‘s top books of 2018! You can read about it here. We can’t think of a better Christmas present. But there’s more good news.

We wrote about Robert Pogue Harrison’s New York Review of Books essay, “Prophet of Envy,” on French theorist René Girard. We’ve also written about his Entitled Opinions radio show and podcasts. The year-end double issue of the U.K.’s Standpoint has published a transcript of one of his 2005 Entitled Opinions interviews with his Stanford colleague – and with a line on the cover, too! (See right.) Excerpt below:

We wrote about Robert Pogue Harrison’s New York Review of Books essay, “Prophet of Envy,” on French theorist René Girard. We’ve also written about his Entitled Opinions radio show and podcasts. The year-end double issue of the U.K.’s Standpoint has published a transcript of one of his 2005 Entitled Opinions interviews with his Stanford colleague – and with a line on the cover, too! (See right.) Excerpt below:

Robert Pogue Harrison: The founding adage of western philosophy is “know thyself.” That’s not an easy proposition. To know yourself means, above all, to know your desire. Desires lurk at the heart of our behavior, determine our motivations, organise our social relations, and inform our politics, religions, ideologies, and conflicts. Yet nothing is more mysterious, elusive, or perverse than human desire.

Our government invests billions of dollars in scientific research every year so we might better understand the world of nature, so that we might continue our pursuit of knowledge, yet commits only a tiny fraction of that to advancing the cause of self-knowledge. Most of our major problems today are as old as the world itself. The problem of reciprocal violence, for example. You would think we would want to understand its mechanisms, its psychology, and its tendencies to spiral out of control. Instead, we keep on perpetuating its cycles much the way our ancestors have done for centuries, and even millennia. Nor are we any closer to knowing the deeper layers of our conflicting and conflict-generating desires than they were.

René, your work has an enormous reach. It branches out into various areas and disciplines — literary criticism, anthropology, religious studies, and so forth. Today, I’d like to focus on what I take to be the foundational concept of all your thinking, namely mimetic desire. Can you tell our listeners exactly what you mean by that term?

René Girard: Mimetic desire is when our choice is not determined by the object itself, as we normally believe, but by another person. We imitate the other person, and this is what “mimetic” means. For example: why have all the girls been baring their navels for the last five years? Obviously, they didn’t all decide by themselves that it would be nice to show one’s navel — or that maybe that one’s navel is too warm, and one must do something about it.

One of San Francisco Chronicle’s top books for 2018

We’ll see the mimetic nature of that desire the day that fashion collapses. Suddenly, it will be a very old-fashioned to show one’s navel and no one will show it any more. And it will all happen because of other people — just as now, it is because of other people that they show it.

RPH: But how far do you want to go in saying that desire — by its very nature, and in human beings — is fundamentally mimetic?

RG: Maybe one can start from this question: what is the difference between need, appetite, and desire? Need is an appetite all animals have. We know very well that if we are alone in the Sahara Desert and we are thirsty, we don’t need a model to want to drink. It’s a need that we have to satisfy. But most of our desires in a civilised society are not like that.

Think of vanity, or snobbery. What is snobbery? In snobbery, you desire something not because you really had an appetite for it, but because you think you look smarter, you look more fashionable, if you imitate the man who desires that object, or who also pretends to desire it.

And later in the interview…

RPH: … I asked in my opening remarks about why can’t we have an institution devoted strictly to the study of vengeance, for example, and work out its logic — reciprocal violence, these kinds of things. We are far from overcoming the behaviour that has characterised human history throughout the centuries.

But let’s move on to another emotion, which is closely linked, obviously, to hatred, vengeance, and jealousy, namely envy. I think envy is a highly underestimated emotion in the human relations. How do you see the role of envy?

RG: I see it the same way. Today envy is the emotion which plays the greatest role in our society, where everything is directed towards money. Therefore you envy the people who have more than you have. You cannot talk about your envy. I think the reason we talk so much about sex is that we don’t dare talk about envy. The real repression is the repression of envy.

And of course, envy is mimetic. You cannot help imitating your model. If you want money very badly, you’re going to enter the same business as the man who is your model. More likely than not, you will be destroyed by strength. So when people talk about masochism and so forth, they are still talking about mimetic desire. They are talking about how we move always to the greatest strength in the direction of the desire we envy most. We do so because that power is greater than ours — and it’s probably going to defeat us again. So there will be what Freud calls repetition in psychological life, which is linked to the fact that we’re obsessed with what has defeated us the first time. Our victorious rival in lovemaking becomes a permanent model. So novelists like Dostoevsky and Cervantes will show you characters who literally asked their rival to choose for them the girl they should love.

And of course, envy is mimetic. You cannot help imitating your model. If you want money very badly, you’re going to enter the same business as the man who is your model. More likely than not, you will be destroyed by strength. So when people talk about masochism and so forth, they are still talking about mimetic desire. They are talking about how we move always to the greatest strength in the direction of the desire we envy most. We do so because that power is greater than ours — and it’s probably going to defeat us again. So there will be what Freud calls repetition in psychological life, which is linked to the fact that we’re obsessed with what has defeated us the first time. Our victorious rival in lovemaking becomes a permanent model. So novelists like Dostoevsky and Cervantes will show you characters who literally asked their rival to choose for them the girl they should love.

Read the whole thing here.

Postscript on 12/18: The actual, physical copies of Standpoint arrived in my Stanford p.o. box today. It’s beauuu-ti-ful! (See photo at left.) Moreover, “Love and Envy in Shakespeare: A Dialogue with René Girard on Mimesis and Desire” leads the “Civilisation” section of the magazine. Thanks to Daniel Johnson and the London staff of Standpoint magazine. What fine work you do! And what a splendid Christmas present – not just for me, but for all of us!