You think you have a messy desk? You have competition! Here are some famously messy ones.

Saturday, October 17th, 2020

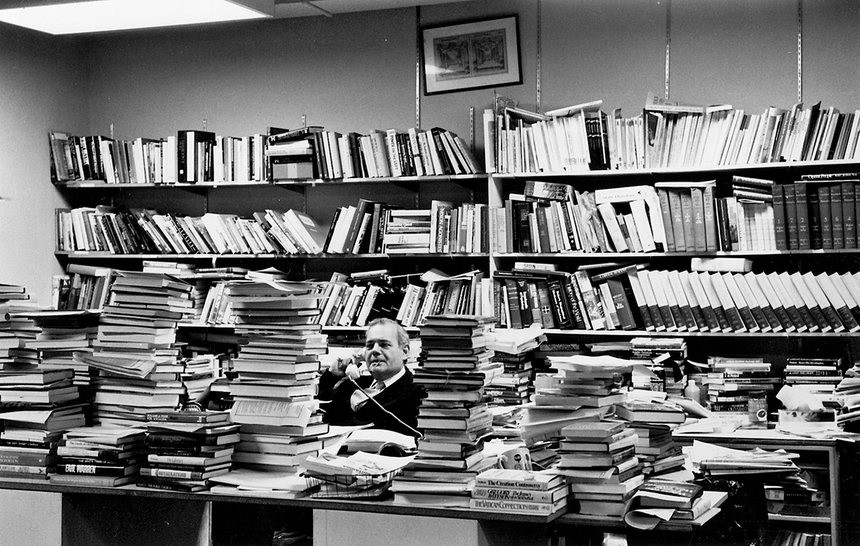

Robert Silvers of New York Review of Books fame. Is he a master or a prisoner of this space? Love to spend an afternoon there.

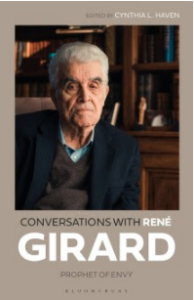

It’s one week before I go on Zoom for Stanford’s 17th annual Company of Authors event at 1 p.m. next Saturday, October 24. My mission: to tell you about my newest book Conversations with René Girard: Prophet of Envy. (Get your free tickets for a reservation here.) Then you will see my messy, messy workspace behind me. The ziggurats of books and papers. The archive that has yet to find a home except in plastic bins spread out across the floor. The huge oak roll-top desk overflowing with rough drafts and pencils and a small clay owl. (A sneak preview at right.)

Home sweet home.

If you wonder why the Book Haven has been so quiet of late, it’s not because we’ve been tidying up. With multiple book deadlines of varying severity rolling over us, we’ve been working 24/7. But we thought we’d take a moment to complain about our bad habits.

I take comfort knowing that I am not alone. At least not in the era of the Google Search. I typed in “famous messy desks” and here’s a few that I found.

I take comfort knowing that I am not alone. At least not in the era of the Google Search. I typed in “famous messy desks” and here’s a few that I found.

My favorite is above, the late, legendary Robert Silvers, one of the founding editors of the New York Review of Books. Though it’s not exactly messy – they are orderly piles, after all – just crowded. I wouldn’t mind spending an afternoon there. in

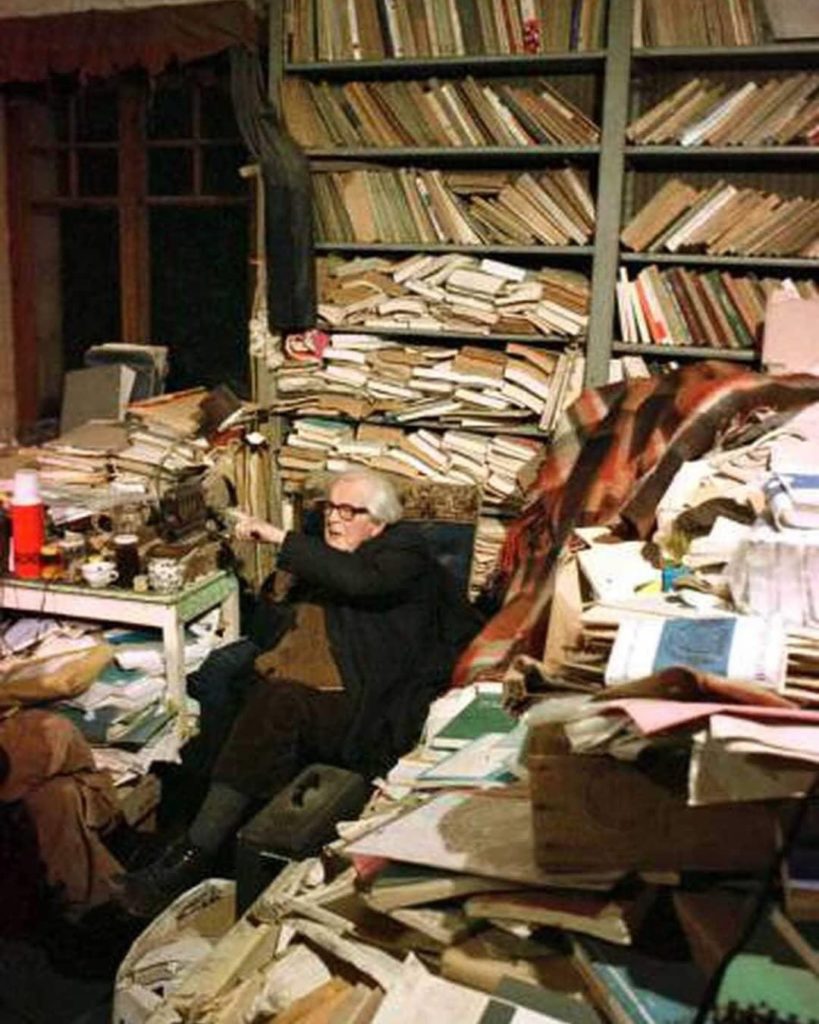

Immediately below, Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget is sprawled in this truly messy space. Clearly, he’s not in California. A good 3.9 earthquake would bury him. But what a way to go!

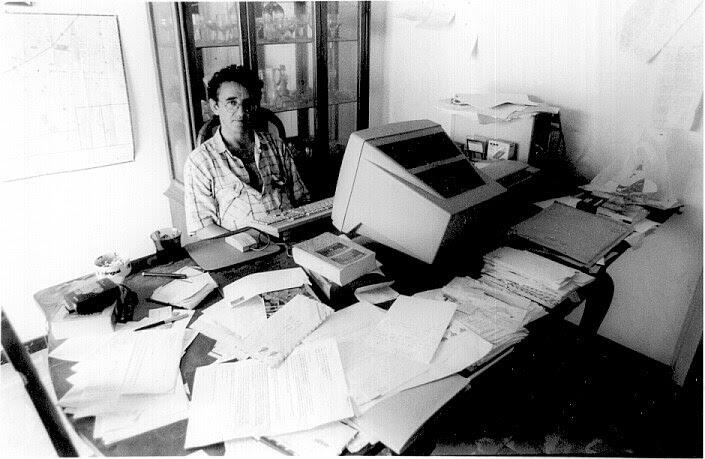

Chilean poet, essayist, and short story writer Roberto Bolaño looks sad, but at ease, among his piles of unanswered correspondence and his old-style computer.

Genius theoretical physicist Alfred Einstein has vacated the premises entirely. In a very literal way. The photo was taken on the day he died in 1955. So He never had to clean it up. Looks homey, though.

Below that, Steve Jobs prowls around what looks like a home office. There are vials with eyedroppers on the shelves.

And finally, always, Mark Twain at ease in 1901. Mess be damned. Who would tell him otherwise?

Feel free to send me the own evidences of your disorganization. I might even publish them as a postscript. It will make me feel better somehow. Because I won’t get around to moving my piles of stuff anytime soon.