“The undulating quality of his thought”: Robert Pogue Harrison remembers Michel Serres

Saturday, October 26th, 2019

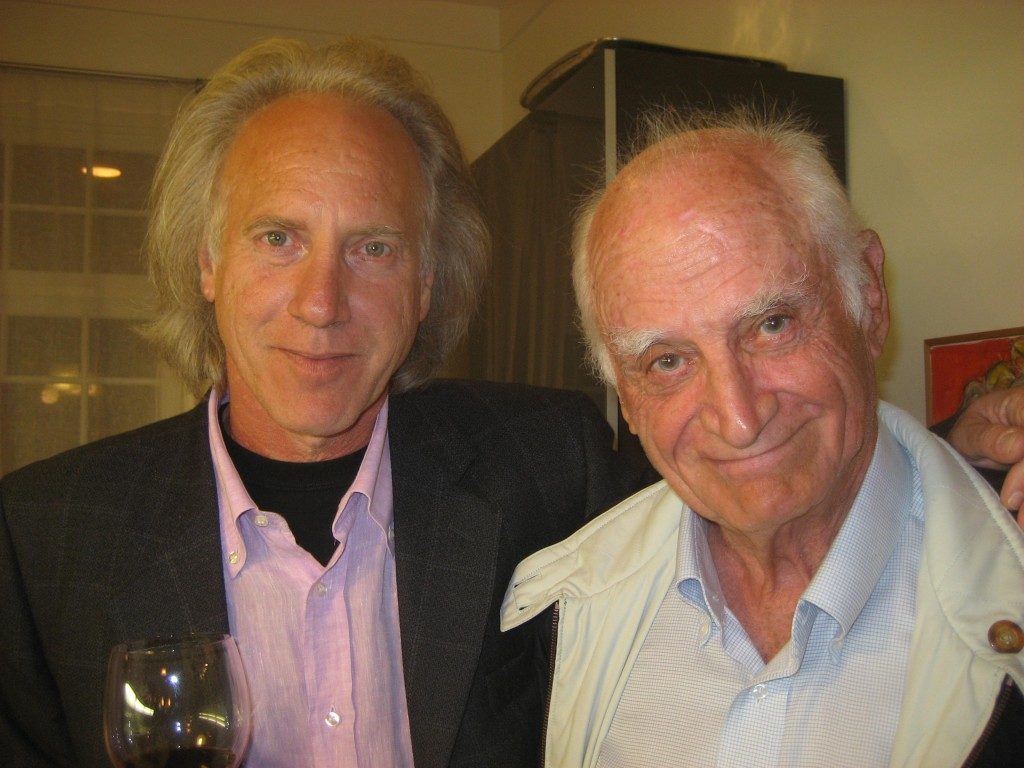

“Michel Serres is indeed Stanford’s ego ideal, even if the institution itself is largely unaware of it.” Remembering the academician at the Stanford Humanities Center on Oct. 21.

Michel Serres, a Stanford professor, a member of the Académie Française, and one of France’s leading thinkers, died on June 1 at age 88. Earlier this week, we published French Consul General Emmanuel Lebrun-Damiens‘s remarks at the memorial conference for him on Monday, Oct. 21. (Read it here.) Below, Robert Pogue Harrison‘s words on that occasion:

When I joined Stanford’s Department of French & Italian as a young assistant professor in the 1980s, I became close friends with Michel Serres. It was he who encouraged me to break out of the straightjacket of narrow academic specialization and to enlarge my conception of what it means to be a humanist. My first book offered an intensive textual analysis of Dante’s Vita Nuova. It was thanks to Michel that that I subsequently went on to write a history of forests in the western imagination, from the Epic of Gilgamesh to our own day. That book, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization, published in 1992, is dedicated to Michel Serres, yet he managed to beat me to the punch. Just before Forests came out, I received a copy of The Natural Contract, which, to my great surprise, Michel had dedicated to me. That dedication, with a quote from Livy (casu quodam in silvis natus), was for me a far bigger deal than the appearance of my book a month or two later.

In the late 80s and 90s, Michel’s seminars at Stanford were attended by a number of junior and senior faculty members. He was the only one I can remember who regularly drew other faculty to his classes. We went not only to learn but to experience the unique aesthetic flourish of his teaching. There was an Orphic quality to his seminars. Michel had a way of enchanting and entrancing his audience. His lectures were musical, operatic performances, with preludes, movements, arias, and crescendos. He created this musical effect by the lyricism of his voice; by the cadences of his sentences; by his measured use of assonance and alliteration; by the poetic imagery of his prose; and by what I would call the undulating quality of his thought. There was a distinct rhythm to his seminars that put their beginning, middle, and end in musical, rather than merely logical, relation to one another. A Michel Serres seminar was a highly stylized affair, both in content and rhetorical delivery – and the audience could not help but break into applause when he concluded with the words “je vous remercie.”

With Serres, the classroom became not only an intellectual space of illumination but also the site of revelations. In addition to what I’ve called the Orphic quality of his teaching, it also had a Pentecostal aspect. (I borrow the term from our onetime Stanford colleague Pierre Saint-Amand, who attended many of Michel’s seminars in the early years.) Michel himself speaks of that particular type of communication in his book, Le Parasite. With Michel, one had the impression at times that something was speaking through him, that he was bringing to the surface deep, long-buried sources of knowledge and wisdom. It was very close to what Hannah Arendt, with reference to Heidegger’s teaching in the 1920s, called “passionate thinking.”

Whether he was teaching literary works or the origins of geometry, you could be sure that Michel would bring together religion and ancient history, anthropology and mathematics, law and literature. He had a wholly new way of reading philosophy, literature, and the tradition in general. Those of us who were drawn to his thought and his seminars developed a taste for complexity. In the heyday of deconstruction, Serres taught us that textualization led to inanition. The surest way to zombify philosophy, literature, or science was to textualize them. He taught by counter-example how to bring into play a heterogeneous plurality of perspectives. Texts were not folded in upon themselves but contained different strata of historical knowledge, of cultural instantiations and practices.

Serres’s model of reading is not easily duplicated. He would bring any number of scientific, religious, and historical deliberations to bear on his reading of authors like Pascal, Balzac, or La Fontaine like Serres was able to do. Serres provided us with a model of complexity for which the word “interdisciplinarity” does not do justice. One could call it a “new encyclopedianism,” but why not call it by a term that he himself coined in his book Genese – “diversalism.”

The concept of diversalism is not opposed to universalism but represents a very different declension of it than the German metaphysical one – a declension that finds universality in multiplicity rather than unity, contingency rather than necessity, and singularity rather than generality. The confluence of different streams of knowledge, diversalism is the very lifeblood of complexity, that is to say the lifeblood of life itself, not to mention of human culture in general.

I would like to think that diversalism – as Michel understood it – defines what Stanford University stands for among institutions of higher learning. In that sense Michel Serres is the local unsung hero of Stanford’s greater ambition to bring all fields of knowledge and research into productive conversation with one another. I would go so far as to say that Serres is – without Stanford even knowing it – this institution’s ego ideal. Let me go even further and say that, in his diversalism, Serres was a very representative member of the Department of French & Italian, which by any measure has been the department of diversalism par excellence. Our colleague Elisabeth Boyi, who is here today, reminds us that diversalism also includes what her friend and fellow traveler Eduard Glissant called “diversality,” namely the admixture of languages, cultural legacies, and ethnic origins in an “archipelago” of diversity, where archipelago means interrelated associations that are not organized hierarchically but laterally.

When you think of colleagues like René Girard, Jean-Marie Apostolides, Sepp Gumbrecht, Brigitte Cazelles, Elisabeth Boyi, Jean-Pierre Dupuy, as well as the younger generation of scholars in French & Italian, many of whom are present here today, you start to wonder whether there is another universe or timeline in which Donald Trump did not win the 2016 presidential election and that the Department of French & Italian figures as the fully acknowledged, rather than discrete, crown jewel of Stanford University. I mean Stanford in its commitment to a genuine diversalistic pursuit of knowledge. But as they say, nemo profeta in patria sua.

If Michel Serres is indeed Stanford’s ego ideal, the institution itself is largely unaware of it. Stanford and Serres always had a courteous but altogether perfunctory relationship. Neither was the explicit champion of the other. That is not unusual. Stanford has a history of accommodating but not exalting some of its most creative endeavors and ventures. Maybe it’s better that way. Be that as it may, Serres was always grateful to Stanford for allowing him to visit twice a year for some three decades. He did much of his best thinking here, interacting with colleagues and walking to the Dish daily. He used to say that he had no complaints about Stanford whatsoever. “Je vie comme un moine et je suis payé come une putain.” Wherever he is now, I’m sure he’s looking on Stanford fondly. Those of us he left behind here in California miss him dearly, and it is fair to say there will never be another one like him in our midst.

I suppose that what I mean is that Sepp is listened to by people who wouldn’t dream setting foot on conferences such as this one. And this raises the question: could Sepp be both one of us and one of them? Could this be a case of intellectual schizophrenia? I don’t think so. There are, to be sure, many connections between what Sepp does in class and what he does outside. He always remained and after all is the same person. However, the attempt to engage vast unknown audiences is something that after all defines his difference vis-à-vis most of us. It is a difference that many of us would quickly grant is a measure of Sepp’s trademark as an intellectual, both public and private, and intellectual for whom the private/public distinction does not obtain. In claiming that Sepp is an intellectual public and private I am thus claiming that he is unlike most of us. … This is very high compliment indeed.

I suppose that what I mean is that Sepp is listened to by people who wouldn’t dream setting foot on conferences such as this one. And this raises the question: could Sepp be both one of us and one of them? Could this be a case of intellectual schizophrenia? I don’t think so. There are, to be sure, many connections between what Sepp does in class and what he does outside. He always remained and after all is the same person. However, the attempt to engage vast unknown audiences is something that after all defines his difference vis-à-vis most of us. It is a difference that many of us would quickly grant is a measure of Sepp’s trademark as an intellectual, both public and private, and intellectual for whom the private/public distinction does not obtain. In claiming that Sepp is an intellectual public and private I am thus claiming that he is unlike most of us. … This is very high compliment indeed.