Steve Wasserman: “The world we carry in our heads is arguably the most important space of all.”

Monday, September 25th, 2017

We’ve written about Steve Wasserman before – here and here and here. On Saturday, he gave the keynote address at the 17th Annual North Coast Redwoods Writers’ Conference at the College of the Redwoods, Del Norte, in Crescent City. The subject: “A Writer’s Space.” He’s given us permission to reprint his words on that occasion, and we’re delighted. Here they are:

Not long after I returned to California last year to take the helm of Heyday Books, a distinguished independent nonprofit press founded by the great Malcolm Margolin forty years ago in Berkeley, my hometown, I was asked to give the keynote speech at this annual conference. I found myself agreeing to do so almost too readily—so flattered was I to have been asked. Ken Letko told me the theme of the gathering was to be “A Writer’s Space.”

In the months that have elapsed since that kind invitation, I have brooded on this singular and curious formulation, seeking to understand what it might mean.

What do we think we mean when we say “a writer’s space”? Is such a space different than, say, any other citizen’s space? Is the space of a writer a physical place—the place where the writing is actually done, the den, the office, the hotel room, the bar or café, the bedroom, upon a desk or table or any available flat and stable surface?

Or is the “writer’s space” an inner region of the mind? Or is it a psychological place deep within the recesses of the heart, a storehouse of emotions containing a jumble of neurological circuitry? Is it the place, whether physical or spiritual, where the writer tries to make sense of otherwise inchoate lives? In either case, is it a zone of safety that permits the writer to be vulnerable and daring and honest so as to find meaning and order in the service of story?

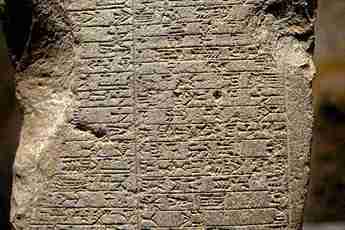

Perhaps it will be useful to begin at the very dawn of writing when prehistory became history. Let’s think, for a moment, about the clay tablets that date from around 3200 B.C. on which were etched small, repetitive impressed characters that look like wedge-shape footprints that we call cuneiform, the script language of ancient Sumer in Mesopotamia. Along with the other ancient civilizations of the Chinese and the Maya, the Babylonians put spoken language into material form and for the first time people could store information, whether of lists of goods or taxes, and transmit it across time and space.

It would take two millennia for writing to become a carrier of narrative, of story, of epic, which arrives in the Sumerian tale of Gilgamesh.

Writing was a secret code, the instrument of tax collectors and traders in the service of god-kings. Preeminently, it was the province of priests and guardians of holy texts. With the arrival of monotheism, there was a great need to record the word of God, and the many subsequent commentaries on the ethical and spiritual obligations of faithfully adhering to a set of religious precepts. This task required special places where scribes could carry out their sanctified work. Think the Caves of Qumran, some natural and some artificial, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, or later the medieval monasteries where illuminated manuscripts were painstakingly created.

First story

Illiteracy, it should be remembered, was commonplace. From the start, the creation of texts was bound up with a notion of the holy, of a place where experts—anointed by God—were tasked with making Scripture palpable. They were the translators and custodians of the ineffable and the unknowable, and they spent their lives making it possible for ordinary people to partake of the wisdom to be had from the all-seeing, all-powerful Deity from whom meaning, sustenance, and life itself was derived.

We needn’t rehearse the religious quarrels and sectarian strife that bloodied the struggle between the Age of Superstition and the Age of Enlightenment, except perhaps to note that the world was often divided—as, alas, it still sadly is—between those who insist all answers are to be found in a single book and those who believe in two, three, many books.

The point is that the notion of a repository where the writer (or religious shaman, adept, or priest) told or retold the parables and stories of God, was widely accepted. It meant that, from the start, a writer’s space was a space with a sacred aura. It was a place deemed to have special qualities—qualities that encouraged the communication of stories that in their detail and point conferred significance upon and gave importance to lives that otherwise might have seemed untethered and without meaning. The writer, by this measure, was a kind of oracle, with a special ability, by virtue of temperament and training, to pierce the veil of mystery and ignorance that was the usual lot of most people and to make sense of the past, parse the present, and even to predict the future.

A porous epidermis

This idea of the writer was powerful. It still is. By the time we enter the Romantic Age, the notion of a writer’s space has shed its religious origins without abandoning in the popular imagination the belief that writers have a special and enviable access to inner, truer worlds, often invisible to the rest of us. How to put it? That, by and large, artists generally, of which writers are a subset, are people whose epidermises, as it were, are more porous than most people’s. And thus they are more vulnerable, more open to the world around them, more alert, more perspicacious. Shelley put it well when he wrote that, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” Think Virginia Woolf.

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers in their person and in their spaces are widely celebrated and revered, imbued with talents and special powers that arouse admiration bordering on worship. It is said that when Mark Twain came to London and strode down the gangplank as he disembarked from the ship that had brought him across the Atlantic, dockworkers that had never read a single word of his imperishable stories, burst into applause when the nimbus of white hair atop the head of the man in the white suit hove into view. Similarly, when Oscar Wilde was asked at the New York customs house if he had anything to declare, when he arrived in America in 1882 to deliver his lectures on aesthetics, he is said to have replied: “Only my genius.”

Applause, applause

Many writers were quickly enrolled in the service of nationalist movements of all kinds, even as many writers saw themselves as citizens in an international republic of letters, a far-flung fraternity of speakers of many diverse languages, but united in their fealty to story. Nonetheless, the space where they composed their work–their studies and offices and homes—quickly became tourist destinations, sites of pilgrimage where devoted readers could pay homage. The objects on the desk, writing instruments and inkwells, foolscap and notebooks, the arrangement of photographs and paintings on their walls, the pattern of wallpaper, the very furniture itself, and preeminently the desk and chair, favorite divan and reading sofa, lamps and carpets, all became invested with a sacredness and veneration previously reserved only for religious figures. Balzac’s home, Tolstoy’s dacha, Hemingway’s Cuban estate, are but three of many possible examples. Writers were now our secular saints.

Somehow it was thought that by entering these spaces, the key to unlocking the secret of literary creation could be had, and that by inhaling the very atmosphere which celebrated authors once breathed, one could, by a strange alchemy or osmosis, absorb the essence that animated the writer’s imagination and made possible the realization of native talent.