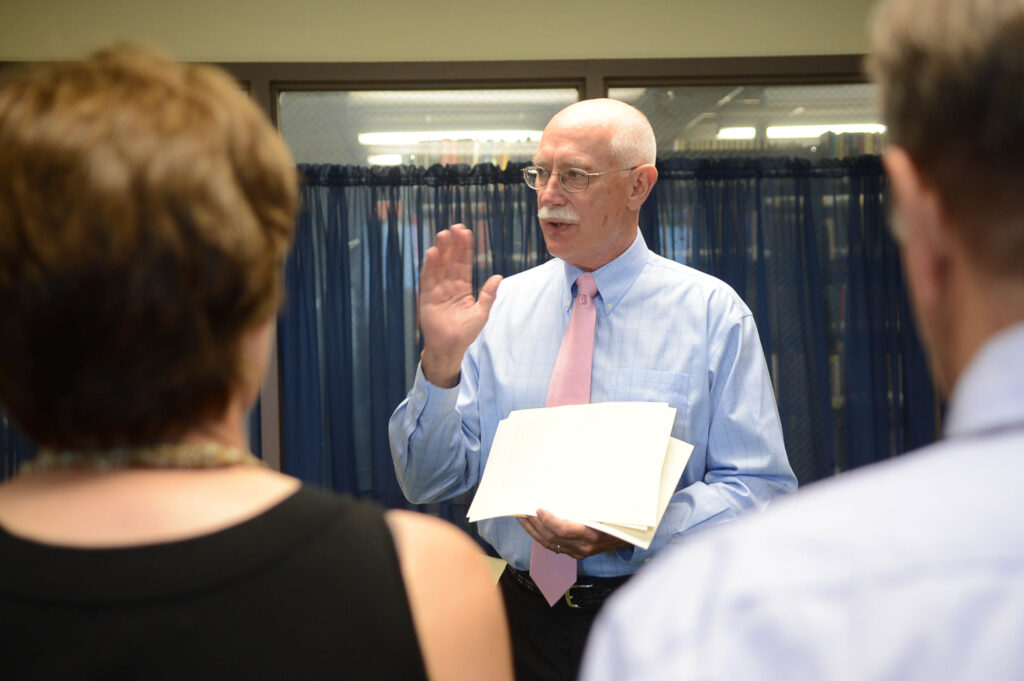

Cheers to the man whose name is a rhyme! Poetry champion Mike Peich turns 80!

Monday, May 20th, 2024

Way back in 1995, a literary movement was born: the West Chester Poetry Conference, with 85 poets and scholars in attendance gathering in the small burg outside Philadelphia. The original core faculty members included Annie Finch, R. S. Gwynn, Mark Jarman, Robert McDowell, and Timothy Steele.

They had a mission. In a world where poetry has become almost irrelevant, the poets gathered in West Chester wanted to return it to a general audience. Their weapons of choice? Traditional forms, rhyme and meter, those age-old tools of the poet’s craft, which fell out of fashion in the last century but were making a startling comeback. Why did it appeal? Because it echoes with cadences that have been familiar to English-speakers for centuries.

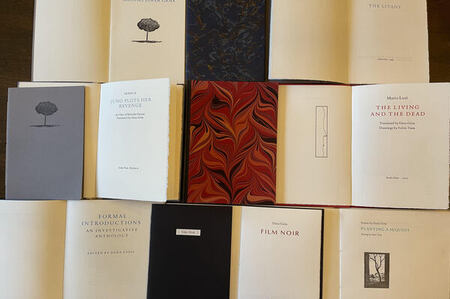

The conference was co-founded by a maverick California poet, Dana Gioia, and a local fine-press printer, Michael Peich. It soon became perhaps the largest such ongoing symposium in America, with more than 200 by the time the century turned. The Philadelphia Inquirer called it “a true event, one of the most important such conferences in the United States.” Over the years, it’s pulled in such heavyweights as Richard Wilbur – arguably America’s greatest living poet – as well as Anthony Hecht and Britain’s Wendy Cope, among others. Together, Gioia and Peich made this small suburban campus into an unlikely literary mecca.

Not everyone was a fan of what the West Chester conference represented. The movement that gave birth to it – loosely called “New Formalism” – has been locked in a David-and-Goliath struggle with several of the more powerful institutions in today’s poetry world. Notable among them is Philadelphia’s prestigious American Poetry Review, which in 1992 published a blistering attack on it as “dangerous nostalgia” with a “social as well as a linguistic agenda.” Another critic labeled the group “the Reaganites of poetry.” And a recent issue of the American Poetry Review makes a dismissive reference to “neo-conservative formalism.”

Well, you can read the whole story here. It’s disappeared from the Philadelphia Magazine online, but we have preserved the article, “The Bards of the ‘Burbs,” just for you.

Meanwhile, many of the West Chester veterans praised him in – what else? – poetry, beginning with Dana himself, riffing on Tennyson‘s “Ulysses” with his good friend and fellow poet David Mason:

ULYSSES IN WEST CHESTER

or

Michael Peich Turns Eighty

It little profits that an idle man

By a still press, with a half-empty can

Of beer should undertake a survey of his life.

One might as well carve water with a knife,

And water passeth underneath a bridge.

He flushes and returneth to the fridge.

The long day wanes. The game shows now begin.

The existential question—switch to gin?

It is the evening makes him think this way,

As repetitious as a roundelay.

He can’t stay up too late, can’t see the stars,

The doctors have forbidden him cigars.

Old age hath yet its honor and its trauma,

From scheming poets and their endless drama,

Their endless readings and their endless woes,

Self-laureled poets with their souls of prose.

No blinded Cyclops roaring in a rage

Is half as awful as some poet’s page.

Such steady service to the Thankless Muse

Would drive a less heroic man to booze.

(A recreation he can’t even try;

His poet friends have drunk his cellar dry.)

But wise Ulysses sees his shelf and smiles.

The books he printed are his Happy Isles.

Turn off the screen, and let the low skies darken.

Time to reread Dick Wilbur, Kees, and Larkin.

Though much is taken, he will undertake—

For Dianne and his worthy spirit’s sake—

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to growse,

Or let another poet in the house.

From Meg Schoerke

Tell all the truth but tell it “Peich”—

Success in Printing lies

Not in Broadsides, nor Matchless proof,

No Letter out of Line—

But Truest—be—the Type of man

For whom Ink Brayers roll—

His Font of Generosity

And Impress on our Soul—

From Leslie Monsour

Dear Mike,

The time has come, now that you’re eighty,

To turn to matters deep and weighty.

By now, you must be sage and wise;

No need for doubt or compromise.

Of lessons, you have gathered plenty.

Your insight measures twenty/twenty.

Now share with us your deepest findings

And what you’ve learned from life’s hard grindings.

And, while you share all this and more,

Don’t hesitate to freely pour,

Along with your profoundest self,

That twelve-year-old Macallan…up there…on the shelf.

From James Matthew Wilson

To Michael Peich on His Eightieth Birthday

The great Romantic poet speaks of acts

Of “unremembered . . . kindness and of love,”

As, in our human lives, redeeming facts,

Graces descending like a blazing dove.

How many are the poets you have aided

In finding their first feet in verse and rhyme?

Your memory of such things may, now, have faded

As do most things beneath the wash of time.

So, at the rounding of these eighty years,

I write to recollect your kindest deeds

While offering you as well my hearty cheers

As your ninth decade in the world proceeds,

Such cheers come as a sonnet to ensure

That they and you alike may long endure.

From Robert B. Shaw

For Michael Peich’s Birthday

Poets, if you are out to seek

a paradigm for life and art,

observe how Peich has scaled his peak.

What’s eighty years? A fresh new start.

From Shirley Geok-lin Lim

Unfortunately,

I never met Mike.

This counts as a strike

Against me. No like

On FaceBook. Dislike

Me. I’ll take a hike,

You poets, a shrike

Among songbirds.

From Mark Jarman & Robert McDowell

Celebrating Michael Peich

Is like riding a Schwinn bike.

Though he’s hardly a tyke,

He’s still someone we like.

He’s younger than Ike,

He’s Mighty Mike!

Need a patched dike?

Depend upon Mike.

Transcontinental Mike

Drives home the golden spike.

You’ll quickly cycle

Through the best rhymes for Michael.

But he is unique

Like the tip of Pike’s Peak.

If it’s favors you seek

Any day of the week

In a pet or a pique

He will soothe you and speak

Of the beauty of books

In crannies and nooks

Handcrafted, handmade

And never mislaid.

That’s the magic of Mike

Whom you know that we like.

On horseback or trike

Our Michael will strike.

And what is our takeaway?

80 bells for his birthday!

And a personal favorite from David J. Rothman:

Michael Peich

Is no longer a tyke.

His thoughts are more weighty

Now that he’s…fifty.

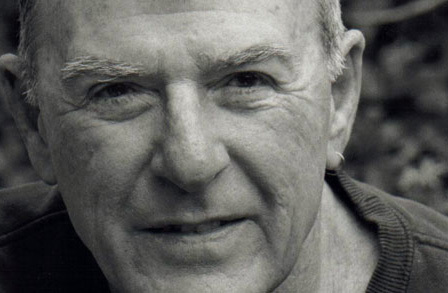

Helen Pinkerton rose from hardscrabble origins to become one of the most thoughtful and graceful poets of her generation. She was born in 1927 in Butte, Montana, the home of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company and possibly the roughest and most corrupt town in the country at the time. (Dashiell Hammett portrays it as Personville in Red Harvest.) Pinkerton had to take a circuitous route on her walk to school each day to avoid the town’s large and thriving red light district. Her father worked in the mines and was killed in 1938 in an accident in one of the shafts in Butte Hill—“the richest hill on earth” during the copper boom. After graduating from high school in 1944, Pinkerton moved with her mother to Palo Alto, where they worked in a cannery. She applied and was admitted to Stanford. She later modestly said that she thought she got in because all the young men were off in the Second World War and the university needed students. Originally intending to study journalism, she took a class from

Helen Pinkerton rose from hardscrabble origins to become one of the most thoughtful and graceful poets of her generation. She was born in 1927 in Butte, Montana, the home of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company and possibly the roughest and most corrupt town in the country at the time. (Dashiell Hammett portrays it as Personville in Red Harvest.) Pinkerton had to take a circuitous route on her walk to school each day to avoid the town’s large and thriving red light district. Her father worked in the mines and was killed in 1938 in an accident in one of the shafts in Butte Hill—“the richest hill on earth” during the copper boom. After graduating from high school in 1944, Pinkerton moved with her mother to Palo Alto, where they worked in a cannery. She applied and was admitted to Stanford. She later modestly said that she thought she got in because all the young men were off in the Second World War and the university needed students. Originally intending to study journalism, she took a class from

“She has written some of the best poems of her generation,” says poet and scholar

“She has written some of the best poems of her generation,” says poet and scholar  Over the years, I have published several articles on Pinkerton, in hopes of bringing her metaphysical lyrics to a wider audience. I see now, however, that I have given short shrift to what may be her most lasting contribution to American letters, her five dramatic monologues in blank verse on the subject of the Civil War. These, I believe, will become classics: miniature epics that, like

Over the years, I have published several articles on Pinkerton, in hopes of bringing her metaphysical lyrics to a wider audience. I see now, however, that I have given short shrift to what may be her most lasting contribution to American letters, her five dramatic monologues in blank verse on the subject of the Civil War. These, I believe, will become classics: miniature epics that, like

Prefer the Wilkes who looked into that face,

Prefer the Wilkes who looked into that face,