On the centenary of the Russian Revolution: what was it like before it was a fait accompli?

Friday, October 13th, 2017

Bolsheviks on the Red Square, 1917

Spiked Review has thrown a spotlight on 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution, an anthology of prose and poetry, edited and often translated by Boris Dralyuk, executive editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books.

His book “does something remarkable for an event seen all too readily in hindsight. As Dralyuk himself puts it, 1917 aims to capture the experience of the revolution among those for whom it was yet to be a fait accompli. We see that for some, it was a source of trepidation, to others, inspiration. But to all, it was unfolding, its destination uncertain.”

From the interview with Boris Dralyuk:

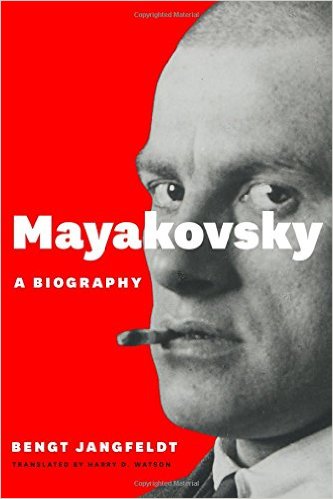

spiked review: Do you feel that many of these writers and poets – the big names like Mayakovsky or Pasternak excepted – have been unfairly neglected outside Russia? And perhaps even inside Russia, too? And, if so, why do you think this is?

Funny Girl: Nadezhda Teffi

Boris Dralyuk: You’re quite right: many of the authors in this anthology have been neglected. The reasons for this neglect are not too difficult to surmise. Writers who fled Soviet Russia out of hostility to Bolshevik rule – and, often enough, fear for their lives – preserved their freedom of expression, but at great cost. Literary stars like [Nadezhda] Teffi – a great humorist whose work had won the admiration of both Nicholas II and Lenin – found themselves writing almost exclusively for an isolated émigré audience. Paris became the capital of the Russian emigration, but many French intellectuals perceived members of the Russian colony as unfashionably conservative and retrograde; to their minds, the émigrés were, in Nabokov’s words, ‘hardly palpable people who imitated in foreign cities a dead civilisation, the remote, almost legendary, almost Sumerian mirages of St Petersburg and Moscow, 1900-1916’.

There was far more interest in translations of new Soviet works than in the melancholy scribbling of Russians who had split off from the march of history, consigning themselves to oblivion. I quoted Nabokov, who saved himself from oblivion by switching languages. Few of his fellow émigrés could manage that transition. They had to wait, on the one hand, for Soviet censorship to collapse, and, on the other, for translators to take up their causes. Teffi won back her Russian readers after 1991, and it is only in the past decade that Anglophone audiences were exposed to sparkling translations of her prose; Robert and Elizabeth Chandler, Rose France, Irina Steinberg, Anne Marie Jackson, and Clare Kitson have ushered in a proper Teffi renaissance in English, and I was grateful to feature two of this master’s pieces, in Rose France’s translation, in 1917. Anyone interested in the great variety of prose that Russians produced in emigration between the wars should pick up Bryan Karetnyk’s brilliant anthology Russian Émigré Short Stories from Bunin to Yanovsky, which was released by Penguin Classics earlier this year.

But it isn’t only émigré writers who have suffered from neglect. Ironically, some of the authors who were most enthusiastic about the October Revolution – the true believers – had been most thoroughly effaced from Russian literary history. I’m thinking of the poets associated with the Proletkult, or ‘proletarian culture’ movement, whose verse from the first years of Soviet rule radiates fiery conviction. In subsequent years, as Soviet economic and literary policy shifted, this conviction gave way to disillusionment. I include the work of three Proletkult poets in my anthology. The dates of their deaths – 1937, 1937 and 1941 – say a great deal. Mikhail Gerasimov and Vladimir Kirillov were both arrested and executed at the height of Stalin’s purges, and Alexey Kraysky died during the blockade of Leningrad. Their work was suppressed or simply forgotten for decades.

Read the rest here.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.