No more billets-doux, no more epistolary novels, no more Collected Letters

Tuesday, October 4th, 2011Write a letter lately? I haven’t either.

According to a story in the Associated Press, nobody else is, either:

For the typical American household these days, nearly two months will pass before a personal letter shows up.

The avalanche of advertising still arrives, of course, along with magazines and catalogs. But personal letters — as well as the majority of bill payments — have largely been replaced by email, Twitter, Facebook and the like.

“In the future old ‘love letters’ may not be found in boxes in the attic but rather circulating through the Internet, if people care to look for them,” said Webster Newbold, a professor of English at Ball State University in Muncie, Ind.

Well, not so. We’re not likely to be able to retrieve them. Such missives are likely to be harbored in defunct email systems on old computers. I save a bunch seven-inch floppies with interviews on them, in hopes I’ll find a computer that can decode them. Nothing like hard copies, even if I can’t lay my hands on them readily.

Voltaire wrote about 15,000 letters during his 83-year life. In more recent times, C.S. Lewis is the patron saint of pen pals. His Collected Letters amount to thousands and thousands of pages. I reviewed the 1,800+ page third volume for the Washington Post here.

Lewis wrote everyone, including T.S. Eliot, the sci-fi maestro Arthur C. Clarke, and the American writer Robert Penn Warren. “Other letters were from cranks, whiners and down-and-out charity cases; he answered them all,” I wrote.

“The pen has become to me what the oar is to a galley slave,” he wrote of the disciplined torture of writing letters for hours every day. He complained about the deterioration of his handwriting, the rheumatism in his right hand and the winter cold numbing his fingers. In the era of the ballpoint, he used a nib pen dipped in ink every four or five words.

Who, in the future, will have volumes of Collected that will be thicker than a slim paperback?

Beyond the prospect of no Collecteds, whole novels have been held together by letters – Laclos‘s Liaisons Dangereuses, for example, or, since we’ve mentioned Lewis, his Screwtape Letters, or his Letters to Malcolm. Or his friend Dorothy L. Sayers‘ mystery novel-in-letters Documents in the Case. Or Johann Wolfgang von Goethe‘s Sorrows of Young Werther and Friedrich Hölderlin‘s Hyperion.

Beyond even that, letters provide pivotal revelations in Jane Austen‘s Pride and Prejudice. Or in almost anything by Henry James. The sudden realization, the catharsis, the flushed cheek…

Beyond even that, letters provide pivotal revelations in Jane Austen‘s Pride and Prejudice. Or in almost anything by Henry James. The sudden realization, the catharsis, the flushed cheek…

Vladimir Nabokov‘s Lolita begins with a letter – the letter that tells of the death, in childbirth, of the title character at age 16. If people read it more carefully, they would have a different view of the “sexy” novel. (Also if they read between the lines of Humbert Humbert’s self-serving pronouncements. But without early training on all those day-after-Christmas letters and learning to write the evasive “thank yous,” how would we learn the most subtle nuances of writing at all?)

The very act of letter-writing consumed hours and hours of people’s time. At Stanford, a whole project, Mapping the Republic of Letters, has evolved from the effort to track the to-and-fro correspondence during the time of the Enlightenment. It turns out that we can map coteries, friendships, cultural epicenters, and famous journeys through letters.

AP again:

The loss to what people in the future know about us today may be incalculable.

In earlier times the “art” of letter writing was formally taught, explained Newbold.

“Letters were the prime medium of communication among individuals and even important in communities as letters were shared, read aloud and published,” he said. “Letters did the cultural work that academic journals, book reviews, magazines, legal documents, business memos, diplomatic cables, etc. do now. They were also obviously important in more intimate senses, among family, close friends, lovers, and suitors in initiating and preserving personal relationships and holding things together when distance was a real and unsurmountable obstacle.” …

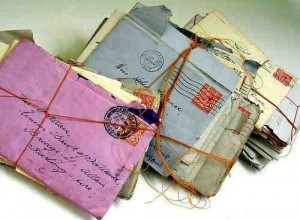

But Aaron Sachs, a professor of American Studies and History at Cornell University, said, “One of the ironies for me is that everyone talks about electronic media bringing people closer together, and I think this is a way we wind up more separate. We don’t have the intimacy that we have when we go to the attic and read grandma’s letters.”

“Part of the reason I like being a historian is the sensory experience we have when dealing with old documents” and letters, he said. “Sometimes, when people ask me what I do, I say I read other people’s mail.”

What about all those books that describes when a pile of a love letters are ceremoniously burned? Or returned to the beloved in a ribbon-tied packet after a break-up? Not quite the same as pressing a “delete” button, is it? However, that sort of rite-of-passage has been on the downswing since the invention of the xerox machine.

What about all those books that describes when a pile of a love letters are ceremoniously burned? Or returned to the beloved in a ribbon-tied packet after a break-up? Not quite the same as pressing a “delete” button, is it? However, that sort of rite-of-passage has been on the downswing since the invention of the xerox machine.

“Letters mingle souls,” as John Donne wrote, but in a wholly different way than what is commonplace on the worldwide web. Despite my sentimentality, however, I, for one, am not sure I’d trade pages on cream-colored vellum for the zip and brevity and immediacy of quickly typed “Sure. Will do.” on my Mac.