Poetry as pleasure – have we forgotten the fun?

Saturday, August 15th, 2015

He hasn’t left, either.

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there.

He wasn’t there again today,

I wish, I wish he’d go away…

When I came home last night at three,

The man was waiting there for me

But when I looked around the hall,

I couldn’t see him there at all!

Go away, go away, don’t you come back any more!

Go away, go away, and please don’t slam the door…

Last night I saw upon the stair,

A little man who wasn’t there,

He wasn’t there again today

Oh, how I wish he’d go away…

I read this poem to my daughter at least two decades ago when she was a very young girl, and she was silent for a long time afterwards, thinking long and carefully. “But he wasn’t there!” she finally exclaimed. “That’s right,” I said. And then she lapsed into silence again, and pondered some more. “But then, how … ? Why did he …?”

I didn’t tell her anything about the poem. I didn’t tell her that it was written by a young man at Harvard in 1899, describing a purportedly haunted house in Antigonish, Nova Scotia. Its author, Hughes Mearns, would go on to be an educator. His notions about encouraging the natural creativity of children, particularly for ages 3-8, were apparently novel at the time. According to a 1940 Current Biography: “He typed notes of their conversations; he learned how to make them forget there was an adult around; never asked them questions and never showed surprise no matter what they did or said.”

I ran across these verses by chance today and, now that my daughter is a woman of twenty-something, I emailed the poem to her and asked her if she remembered it. “Wow! Yeah! I do remember that poem!” Without analysis or explanation, the poem had lodged in her memory, undisturbed for the last two decades. The poem may not qualify for the immortals sweepstakes, and yet it was, clearly, “memorable speech.”

Which brings me to Dana Gioia‘s major essay, “Poetry as Enchantment,” in the current issue of Dark Horse. (It’s online, here.)

Which brings me to Dana Gioia‘s major essay, “Poetry as Enchantment,” in the current issue of Dark Horse. (It’s online, here.)

“In the western tradition, it has generally been assumed that the purpose of poetry is to delight, instruct, console, and commemorate. But it might be more accurate to say that poems instruct, console, and commemorate through the pleasures of enchantment. The power of poetry is to affect the emotions, touch the memory, and incite the imagination with unusual force. Mostly through the particular exhilaration and heightened sensitivity of rhythmic trance can poetry reach deeply enough into the psyche to have such impact. (How visual forms of prosody strive to achieve this mental state requires a separate inquiry.) When poetry loses its ability to enchant, it shrinks into what is just an elaborate form of argumentation. When verse casts its particular spell, it becomes the most evocative form of language. ‘Poetry,’ writes Greg Orr, ‘is the rapture of rhythmical language.’”

I doubt he had a poem like “Antigonish” in mind, and yet I think we would be unwise to dismiss a poem that lodges so securely in a child’s imagination. In the absence of religion today, it may be the closest they come to mystery. Again from Dana:

Academic critics often dismiss the responses of average readers to poetry as naïve and vague, and there is some justification for this assumption. The reactions of most readers are undisciplined, haphazard, incoherent, and hopelessly subjective. Worse yet, amateurs often read only part of a poem because a word or image sends them stumbling backwards into memory or spinning forward into the imagination. But the amateur who reads poetry from love or curiosity does have at least one advantage over the trained specialist who reads it from professional obligation. Amateurs have not learned to shut off parts of their consciousness to focus on only the appropriate elements of a literary text. They respond to poems in the sloppy fullness of their humanity. Their emotions and memories emerge entangled with half-formed thoughts and physical sensations. As any thinking person can see, such subjectivity is an intellectual mess of the highest order. But aren’t average readers simply approaching poetry more or less the way human beings experience the world itself?

Life is experienced holistically with sensations pouring in through every physical and mental organ of perception. Art exists embodied in physical elements—especially meticulously calibrated aspects of sight and sound—which scholarly explication can illuminate but never fully replace. However conceptually incoherent and subjectively emotional, the amateur response to poetry comes closer to the larger human purposes of the art—which is to awaken, amplify, and refine the sense of being alive—than does critical commentary.

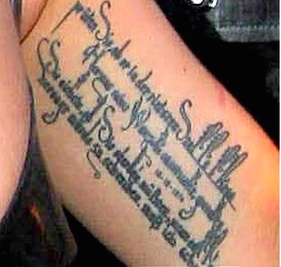

As Rainer Maria Rilke pointed out in his “Sonnets to Orpheus”: “Gesang ist Dasein,” or “Life is singing.” His words meant enough to Lady Gaga to that she had them tattooed on her arm, a distinctly modern kind of tribute. Dana points out that William Blake‘s “The Tyger” is the most anthologized poem in the English language – children love it, love its rhythm and its images, even though they have no idea what it means. Probably nobody does.

Gaga over Rilke. Who knew?

It is significant that the Latin word for poetry, carmen, is also the word the Romans used for a song, a magic spell, a religious incantation, or a prophecy—all verbal constructions whose auditory powers can produce a magical effect on the listener. Ancient cultures believed in the power of speech. To curse or bless someone had profound meaning. A spoken oath was binding. A spell or prophecy had potency. The term carmen still survives in modern English (via Norman French) as the word charm, and it still carries the multiple meanings of a magic spell, a spoken poem, and the power to enthrall. Even today charms survive in oral culture. Looking at a stormy sky, surely a few children still recite the spell:

Rain, rain

go away.

Come again

some other day.

Or staring at the evening sky, they whisper to Venus, the evening star:

Star light, star bright,

First star I see tonight,

I wish I may, I wish I might

Have the wish I wish tonight.

A rational adult understands that neither the star nor the spell has any physical power to transform reality in accordance with the child’s wish. But the poet knows that by articulating a wish, by giving it tangible form, the child can potentially awaken the forces of imagination and desire that animate the future. As André Breton proposed, ‘The imaginary tends to become real.’

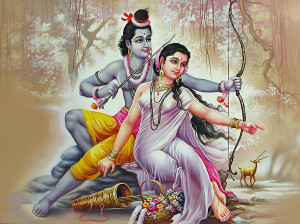

Every time I hear the first schoolyard rhyme, I remember the version I heard in India, where the children sing:

Every time I hear the first schoolyard rhyme, I remember the version I heard in India, where the children sing:

Rain, rain

go away.

Ram and Sita

Want to play.

It’s just as effective in that hemisphere. The same carmen.

I have many thoughts about Dana’s essay – I’ve barely scraped the surface. I hope to explore it in the coming days, after I’ve met a few deadlines. Meanwhile, you can catch up by reading Dana Gioia’s whole essay here.