“Those who read books own the world.” Lost languages, an Algonquin Bible, the Herzogs, and more

Friday, March 30th, 2018

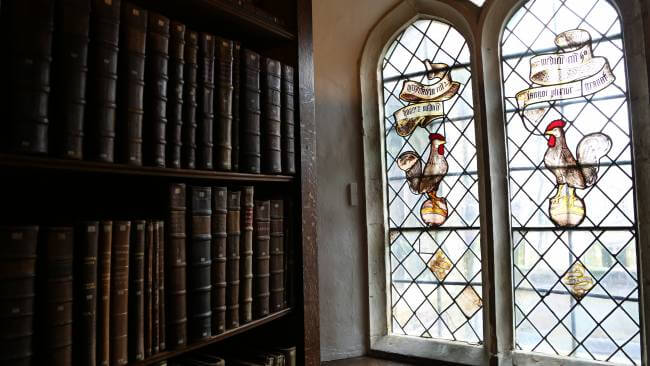

A stroll down the corridors of Cambridge’s treasure house.

I visited the Old Library at Jesus College, Cambridge, last week. Prof. Stephen Heath gave an enlightening show-and-tell of the library’s incunabula to me and my fellow pilgrims, John Dugdale Bradley and Michael Gioia (Stanford alums, both). He brought out an astonishing succession of treasures, including Thomas Cranmer‘s Bible, with its triple columns for comparing the original language (Greek, on the pages I saw) to the Vulgate Latin and English.

“What would you like to see last?” he asked me. What could I say? I had no idea what wonders might be in the back rooms. “Surprise me,” I said.

Marvels tucked away in a corner of Cambridge

And so he did. He brought out another Bible, this one from America. It was a 1663 Bible translated phonetically by John Eliot. The Natick dialect of Algonquin had no written form until he gave it one. He inscribed the particular presentation copy under my fingers for his alma mater at Cambridge, Jesus College. Was the Eliot name a coincidence? I remember a prominent New England family that spawned another famous Eliot, also with one “l”. On the other hand, I also knew that spellings of surnames were very fluid even into the 19th century.

When I got back to California, I checked on John Eliot, the Puritan missionary. He is indeed distantly related to T.S. Eliot, from the same Brahmin family in Massachusetts. Both descended from Andrew Eliot, whose family came to America via Yeovil and East Coker, Somerset.

But the Algonquin Bible haunted me for another reason: I recently attended a private screening in San Francisco of photographer’s Lena Herzog‘s Last Whispers, about the mass extinction of languages. I meant to tell her about the Algonquin Bible on my return, but now this blogpost will have to do. Perhaps the Algonquin language, which still has more than three thousand speakers, owes something to Eliot’s efforts.

But the Algonquin Bible haunted me for another reason: I recently attended a private screening in San Francisco of photographer’s Lena Herzog‘s Last Whispers, about the mass extinction of languages. I meant to tell her about the Algonquin Bible on my return, but now this blogpost will have to do. Perhaps the Algonquin language, which still has more than three thousand speakers, owes something to Eliot’s efforts.

The coincidences continued: this week, a new friend, Paul Holdengräber of the New York Public Library, sent me the link for his interview several years ago with Lena’s husband, the unconventional filmmaker Werner Herzog. The Q&A, “Was the Twentieth Century a Mistake?”, touches on the same subject – lost languages. (His comments are unrelated to Lena’s project, although their interests on the matter converge.) So here’s a hefty and relevant excerpt from the conversation between the two men:

WH: But, Paul, before we go into other things, I would linger a little on the twentieth century. And one of the things that is quite evident and looks like a good thing in the twentieth century is the ecologists’ movement. It makes a lot of sense, the fundamental analysis is right. The fundamental attitude they have taken is also right, but we miss something completely out of the twentieth century, which is—

Lena Herzog: a lover of language

PH: Culture.

WH: What went wrong in the culture, yes. That is, we see embarrassments like whale huggers, I mean, you can’t get worse than that, or tree huggers, even, such bizarre behaviour. And people are concerned about the panda bear, and they are concerned about the well-being of salad leaves, but they have completely overlooked that while we are sitting here probably the last speaker of a language may die in these two hours. There are six thousand languages still left, but by 2050, only 15 percent of these languages will survive.

PH: So we are paying attention to the wrong things.

WH: No, to pay attention to ecological questions is not the wrong thing, but to overlook the immense value of human culture is. More than twenty years ago I met an Australian man in Port Augusta in an old-age home and he was named “the mute.” He was the very last speaker of his language, had nobody with whom he could speak and hence fell mute, fell silent. He had no one left, and of course he has died since then. And his language has disappeared, has not been recorded. It’s as if the last Spaniard had died and Spanish literature and culture, everything has vanished. And it vanishes very, very fast. It vanishes much faster than anything we are witnessing in terms of, let’s say, mammals dying out. Yes, we should be concerned about the snow leopard, and we should be concerned about whales, but why is it that nobody talks about cultures and languages and last speakers dying away? There’s a massive, colossal, and cataclysmic mistake that is happening right now and nobody sees it and nobody talks about it. So that’s why I find it enraging that people hug whales. Who hugs the last speaker of an Inuit language in Alaska? So it just makes me angry when I look back at the twentieth century, and I’m afraid it continues like that. And we have got into a meaningless consumer culture, we have lost dignity, we have lost all proportion.

“Ah, people. It’s the books that matter!” (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

PH: In terms of preserving culture, preserving language, we can think of this library, which has many millions of books underground, seven floors of books, and it goes under Bryant Park.

WH: Paradise.

PH: Paradise, as you called it, but when we were underground, you asked the librarian: “In the case of a holocaust, what would we do with the precious books?” And the librarian was rather anxious about that question. [laughter] No provisions had yet been made, and I don’t know if they’ve been made since your question. But I remember the librarian wondering how to answer it. And he said, “Well, in the case of a holocaust, maybe we will come here.” And you said, “Ah, people. It’s the books that matter!” Do you remember that?

WH: Yes, it sounds misleading in the context of the previous, but please continue. [laughter]

PH: Well, the books are the repository of our memories and our culture. So that these languages that are disappearing as we are talking now have a place where they’re archived, where they’re kept, even if the culture itself has become mute, it still can be studied.

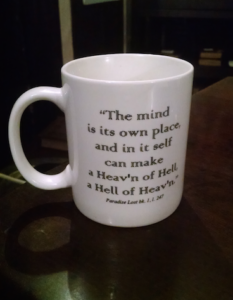

WH: But most of the six thousand still-spoken languages are not recorded in written form. So then they disappear without a trace. That’s evident. But, yes, books, sure, we must preserve them and we must somehow be cautious and careful with them, because they carry our culture—and, of course, those who read books own the world, those who watch television lose it. So be careful and be cautious with the books.

Tom Eliot has formidable forebears.

PH: And what you do with your time.

WH: Yes, but we do have disagreements of what are the most precious ones that we would keep. Of course, you would go for James Joyce immediately, and I have my objections, because I think he’s—

PH: Who would you go for?

WH: Hölderlin. No, I mean James Joyce isn’t really bad, but—

PH: James Joyce is on a trajectory for you—

WH: Which went somewhere wrong—

PH: Somewhere wrong, starting with Petrarch and then going to someone such as Laurence Sterne.

WH:. Yes, Laurence Sterne is somehow a beginning in modern literature, where literature really became modern but also went on a detour and the result—

PH: A detour from what?

Hardcore?

WH: Detour from what, yes—that’s not easy to say, a detour that leads let’s say to Finnegans Wake, where literature should not end up. It’s a cul de sac, in my opinion, and much of James Joyce is a cul de sac, per se. But at the same time that he was writing, there were also people like Kafka, for example, and Joseph Conrad. I have a feeling there is something hardcore, some essence of literature; and you have it in a long, long tradition and you find it in Joseph Conrad, you find it in Hemingway, the short stories, you find it in Bruce Chatwin, and you find it in Cormac McCarthy.

You can read the whole fascinating interview at the literary journal Brick here. But I can’t help but wonder about something else, related to hugging pandas and kissing whales. This may be the very first era in history where there has been so much sentimentality and affection for animals, and comparatively little for babies and children. (This vegetarian cat-lover pleads guilty, at least a bit.) Why is that? And what does that say for the future of the race?

Meanwhile, enjoy this Huron carol, in a language now extinct. Jean de Brébeuf, a Jesuit missionary wrote this carol in Wendat (Wyandot) sometime before he was martyred in 1649 – fourteen years before Eliot’s Algonquin Bible.

Venclova’s artful, frequently formal verse plays in that area where the metaphysical and political overlap — the nothings of

Venclova’s artful, frequently formal verse plays in that area where the metaphysical and political overlap — the nothings of  On Sunday,

On Sunday,

Humble Moi also spoke at the Russian Cultural Centre that evening, but my topic was

Humble Moi also spoke at the Russian Cultural Centre that evening, but my topic was