“A window opening when doors were slamming shut all around me”: how John Fante changed a convict’s life

August 25th, 2023

Please join us at Stanford on for a discussion of John Fante‘s 1939 novel Ask the Dust at 7 p.m. (PST) on Tuesday, Sept. 19, at Levinthal Hall in the Stanford Humanities Center, 424 Santa Teresa Street on the Stanford campus. It’s a hybrid event, so come virtually or in person. REGISTER FOR THE EVENT ON THE LINK HERE! The event is free and open to the public. Walk-ins are welcome, but registration is encouraged, whether you plan to attend virtually or in person. Read more about the event here.

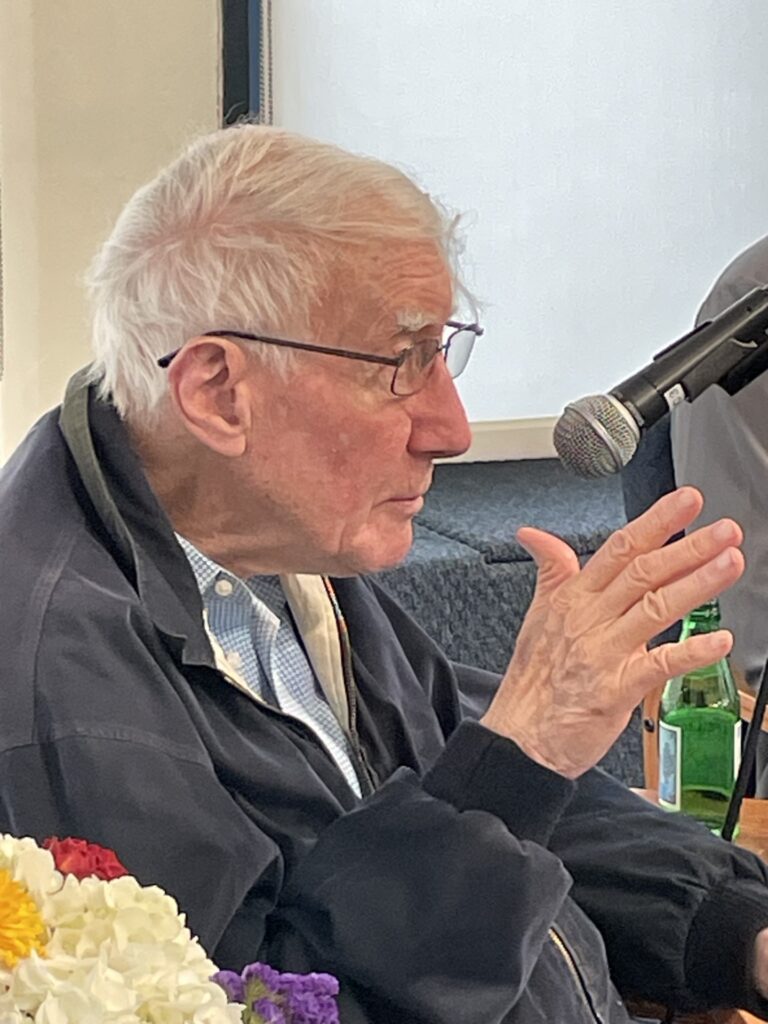

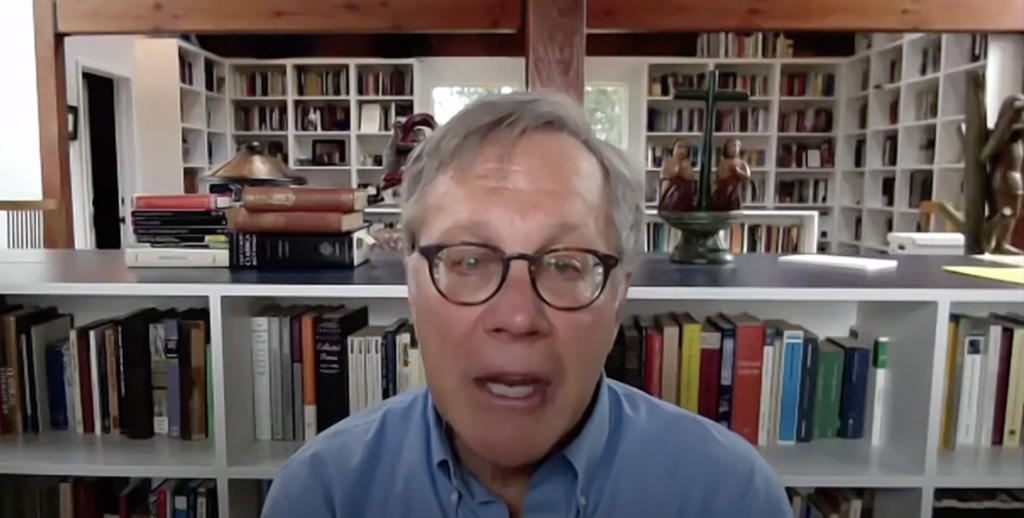

Another Look takes on authors and books that we think deserve more attention. Fante’s Ask the Dust was forgotten for decades after first appearing in 1939. Since being rediscovered in the 1980s, the novel has gained an enthusiastic international audience and influenced many writers. How much of an influence did Fante’s Ask the Dust have? Read the story below, from a Shoshone-Paiute American Indian prisoner whose life was changed by an encounter with Fante’s remarkable novel. Author Joel Williams’s story, republished from Fordham University Press’s John Fante’s ASK THE DUST: A Joining of Voices and Views (2020) with his permission, comes to us courtesy Stephen Cooper, English Professor at California State University, Long Beach. He is perhaps the world’s leading expert on John Fante.

In addition to the Italian Cultural Institute of San Francisco, this event is co-sponsored by the Continuing Studies Program and the Division of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages at Stanford.

I remember exactly where I was and what I was doing when I first heard about the Los Angeles writer, John Fante. The year was 2008 and the place was Mule Creek State Prison, a maximum-security California penitentiary where I was dragging in my twenty-second year on a twenty-seven-to-life sentence.

I was on the yard, hanging out with a couple of other skins near the pull-up bars, when we heard the gunshot. Men everywhere dropped. It was the guard tower’s mini-14, a totally different sound from the usual 40mm “Big Bertha” riot-control block gun. I had suspected something was about to go down ever since another skin — the term we Natives used for each other — had warned me to keep on my toes. Somebody was going to get moved on.

Stretched out prone in the dirt I lifted my head an inch to eyeball the yard. Guards with batons out and keys jangling on their utility belts ran past with medical staff trailing behind. Cordite filled the air as one man was hoisted onto a gurney and another was led off in handcuffs. Beside me Bear, a skin nicknamed for his size, rested his chin on a paperback.

“What book you got?” I asked.

“You don’t wanna read this.”

“Why’s that?”

“Cause you won’t give it back!”

I smiled and he tossed it over, something to while away the next several days when the whole prison would be on lockdown. Hours later, when we were told to get up and go back to our cells, I stuffed the book in my back pocket.

My neighbor, Norm, later told me through the vent that the guy who got stabbed on the yard was my cellmate, a Maidu Indian named Lance. I was stunned. Sure, Lance had a gambling jones and was always in debt. Sure, he smoked too much herb. But hell, he was a nice enough guy and for me that counted, what with most everyone else out to pick your pocket and cut your throat. So sure, the news hit me hard.

To get my mind off things I picked up Bear’s book. It didn’t look like much — no flashy cover, no promise of action or sleaze. The title was an odd one, Ask the Dust, by a guy from my stomping grounds in Los Angeles. His name was John Fante and I’d never heard of him but as I flipped through the first few pages I saw Bukowski’s name. I knew who he was so I read his introduction. And Bukowski revered John Fante. My literary hero, Bukowski, had a hero himself. I stirred up a cup of instant coffee, climbed into my bunk, and set off on a long night of reading.

And what a night it turned out to be. Fante’s character Arturo Bandini pulled me into a Los Angeles I’d never experienced, an earlier world colored with subtle shades of poetry and streaks of vivid emotion. Bandini was exuberant, alive, searching. I reread sentences, whole passages, soaking in the beauty of Fante’s words, wringing every nuance of meaning from his prose. And as always happened when I savored another writer’s work, I felt the tug of jealousy. I too wanted to create beautiful works and move people, and once again I’d been beaten to the punch.

Read the rest of this entry »