From a postcard in the new collection. Brodsky ties a shoelace on the morning of his departure from Leningrad in 1972. (Copyright: Lev Poliakov)

When the Soviet Union expelled the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky in 1972, he already had a few friends waiting for him in the West. One of them, Diana Myers, would remain a confidante until the Nobel laureate’s death in 1996. The London home she shared with her husband, the translator Alan Myers, became his English pied-à-terre.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives at Stanford has recently acquired Diana Myers’ collection of Brodsky’s papers, including letters, photos, drafts, manuscripts, artwork and published and unpublished poems.

“We were keenly interested in adding the Joseph Brodsky papers collected by his friend Diana Myers to our vast archives on Russia and making them accessible right away,” said Eric Wakin, the Robert H. Malott Director of the Hoover Library & Archives.

“With Hoover’s significant holdings on the poet in its Irwin T. and Shirley Holtzman Collection, and the recently acquired Joseph Brodsky papers from the Katilius Family Archive at the Green Library, we’re honored that Stanford has become a notable center for Brodsky studies in the United States.”

The new acquisition documents Brodsky’s enormous capacity for friendship and his long love affair with the English language.

“I am a patriot, but I must say that English poetry is the richest in the world,” he once told an American student visiting Leningrad in 1970 – strong words for the man who would become one of the preeminent Russian poets of the last century.

Brodsky, who settled in the United States, was fascinated by the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. His landmark poem “Elegy to John Donne” was written in 1962, when he knew very little of Donne’s work. It brought him international attention. He began translating and writing English poetry during his 1964-65 internal exile in Norenskaya, near the Arctic Circle.

When the newlywed Myers arrived in London from the Soviet Union in 1967, she was carrying an armful of flowers to lay at the feet of John Donne’s effigy in St. Paul’s Cathedral. The specific request from Brodsky was her first stop in her new homeland.

In a letter Brodsky wrote to Alan Myers a few months before his exile, he requested more information about George Herbert, Richard Crashaw and Henry Vaughn. He sought guidance in finding the best editions of Ben Jonson, Henry King, Walter Raleigh and John Wilmot. An undated and unpublished poem in the collection seems to be an experiment written under their sway.

On another page in the collection, he adds his own illustrations to a few passages from Shakespeare, who anticipated the metaphysical poets.

Fifteen pages of holograph poems in the collection document the slow progression from an idea to a finished poem, with notations, corrections and amendments – all likely of interest to Brodsky scholars. “You can see how it worked, to the final version,” said archivist Lora Soroka. “It’s something that gives insight into his work.”

“It’s everyday life – everyday life when he was there, in England,” she said. “This is definitely our star collection – not big, but stellar.”

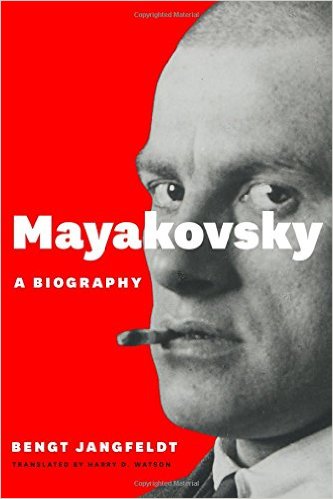

The collection also includes 70 letters from Brodsky, as well as correspondence to him from such figures as Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Swedish translator and author Bengt Jangfeldt, Australian poet Les Murray and others; 25 pages of notes and drafts; five self-portraits, a landscape, and a still life, all in black chalk; an elaborate wedding card he created and illustrated for the couple; a transcript of his 1964 Soviet trial for “parasitism;” and other records.

Brodsky in 1988.

Friendship and hospitality

Myers, who died of cancer in 2013, was born Diana Abaeva, ethnically an Ossetian, whose prominent father had been politically purged and shot under Stalin’s regime in the 1930s. She grew up in Moscow and Tblisi, in the Caucasus Mountains – Brodsky once traveled to Tblisi to visit when he was impatient for her return to Leningrad.

Friends recalled that she was small and slender, with straight dark hair, an aquiline nose, and a radiant smile that was slightly dimmed by nicotine stains, for she smoked almost as ferociously as Brodsky did.

Like Brodsky, she lived for literature and was impractical, even unworldly. One friend recalled she had a slightly languid “Eastern” air. On one page in the collection Brodsky calls her “queen of the couch.”

She was “very intelligent and thoughtful and idiosyncratic,” said University College London’s Faith Wigzell, who had been a close friend of Brodsky’s as well as a colleague of Myers.

Her great gift was for hospitality as well as intellectual conversation: “She was the most relaxed and welcoming hostess. Her home was an international hall of residence. People came to just sit around. She was an excellent cook,” said Wigzell.

For Brodsky, Myers was a means to continue the literary and cultural conversations that had started in Leningrad. In exile, he would continue to consult her, phoning from around the world to read his latest poem and get her opinion. He said she had insights unlike anyone else’s.

Alan Myers, who died in 2010, became an important early translator for Brodsky’s poetry and prose, publishing in the New York Review of Books, The New Yorker and the Times Literary Supplement. In one letter, Brodsky told Myers that he would be paid “substantially, I think” for his New Yorker work, and he reminded his translator that he was looking after his interests.

Brodsky’s “In England” cycle is dedicated to the couple. In the “East Finchley” section, both make an appearance in their London home. In addition, the sections “York: In Memoriam W.H. Auden” and “Stone Villages,” recall trips the three took to W.H. Auden’s birthplace in the northern city of York, an ancient Roman stronghold. (Auden had been Brodsky’s mentor, protector, and friend – and another vital link to England.)

“Joseph found our sleepy residence very relaxing,” Alan Myers recalled in an interview from 2003-04. He remembered him as “a radiant source of wit, generosity of soul and exaltation.”

“No one who knew him well thought it other than a privilege to share the planet with him,” he said.

***

A selection from the Joseph Brodsky papers is included in the current exhibition Unpacking History: New Collections at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, at the Herbert Hoover Memorial Exhibition Pavilion until February 25, 2017. For more information about hours and access to the collections, visit the

Hoover Library & Archives website.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.

The word “love-boat” suggested romantic reasons, but also created a mystery, for Mayakovsky’s tangled love life was mostly unknown to the general public. At the time of his death he was simultaneously involved with three different women: his longtime mistress, Lili Brik, with whom he had spent most of his adult life in a bohemian ménage à trois (together with her husband, Osip Brik), but who was just then involved with a movie director; Tatyana Yakovleva, a striking young White Russian whom Mayakovsky had met in Paris and asked to marry him, but who had just married a Frenchman instead; and Veronika Polonskaya, a sultry young stage actress, also married, to whom he had also proposed marriage. Emotionally he was a wreck, and his death might have been precipitated by his relations with any one of his paramours.