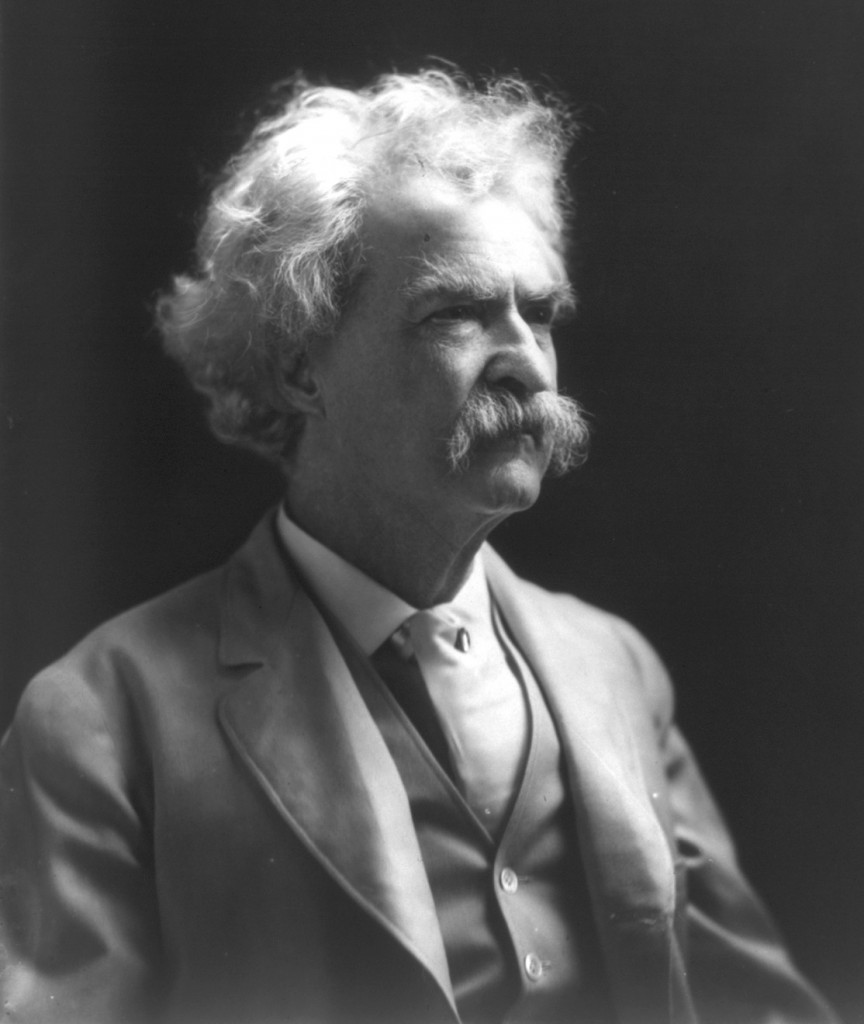

First the Book Haven — then the world. The Huck Finn “n-word” ignites the nation.

Tuesday, January 4th, 2011Well, well, well. We don’t like to brag … not much, anyway … but the whole world seems to have picked up on the Huck Finn and the n-word story, which started here a few day ago, thanks to a reader tip. (If you find a story prior to our Dec. 31 post, let us know. We’re curious.) Another case of the power of the blog, even a relatively obscure one. We’re not Huffington Post, after all.

We started it, Books Inq picked it up Jan. 2, Bookshelves of Doom carried it later in the same day … then Publisher’s Weekly ran a story yesterday, the Entertainment Weekly published an article here, which was deluged with over 1,000 comments.

Unsurprisingly, EW writes:

Unsurprisingly, there are already those who are yelling “Censorship!” as well as others with thesauruses yelling “Bowdlerization!” and “Comstockery!”

Actually, we used the word “Bowdlerization,” and think people are smart enough to know the origins of the word and the 19th century editor Thomas Bowdler who made Shakespeare “respectable” for the fainting couch crowd.

EW continues:

The original product is changed for the benefit of those who, for one reason or another, are not mature enough to handle it, but as long as it doesn’t affect the original, is there a problem?

Frank Wilson at Books Inq exploded at that one in a post titled “Dumb Reaction“: “Well, the point is that it does affect the original. Something else from Wittgenstein: ‘One age misunderstands another; and a petty age misunderstands all others in its own nasty way.'”

CNN picked up the EW story — and from there, the world. From CNN:

Quote of the day: “What’s next? We take out the sexual innuendo from Shakespeare? Or make Lenny Small “normal”? How about cut all the violence out of Clockwork Orange? ” –AA

A pretty close paraphrase of what we said.

jujube said, “So it’s a children’s edition of ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ Adults can and should still read the original. I don’t get the outrage.”

Bobby said, “So we take the ‘n’ word out of Huck Finn, but all of these rappers and hip hop stars still say it every other word, and that’s fine?”

Publishers Weekly actually went so far as to write the n-word, which occurs in Twain’s book 219 times. It also noted that Twain himself defined a “classic” as “a book which people praise and don’t read.” This one may be different. Its article also notes that the new edition dispenses with the “in-word” — that is to say, “Injun.”

Publishers Weekly actually went so far as to write the n-word, which occurs in Twain’s book 219 times. It also noted that Twain himself defined a “classic” as “a book which people praise and don’t read.” This one may be different. Its article also notes that the new edition dispenses with the “in-word” — that is to say, “Injun.”

“Dr. Gribben recognizes that he’s putting his reputation at stake as a Twain scholar,” said [NewSouth cofounder Suzanne] La Rosa. “But he’s so compassionate, and so believes in the value of teaching Twain, that he’s committed to this major departure. I almost don’t want to acknowledge this, but it feels like he’s saving the books. His willingness to take this chance—I was very touched.”

We posted a reply from NewSouth this morning as a postscript on our original post.

By the way, Garrison Keillor wrote a reaction to the newly published Autobiography of Mark Twain in the New York Times a few weeks ago here: “Samuel L. Clemens was a cheerful promoter of himself, and even after he’d retired from the lecture circuit, the old man liked to dress up as Mark Twain…” Spoiler: He didn’t like it much.