A place for “Literary Friendships.”

It was not an easy interview, but Colm Tóibín did his gamely best to interview László Krasznahorkai at the London Review of Books inaugural event for “Literary Friendships” last week.

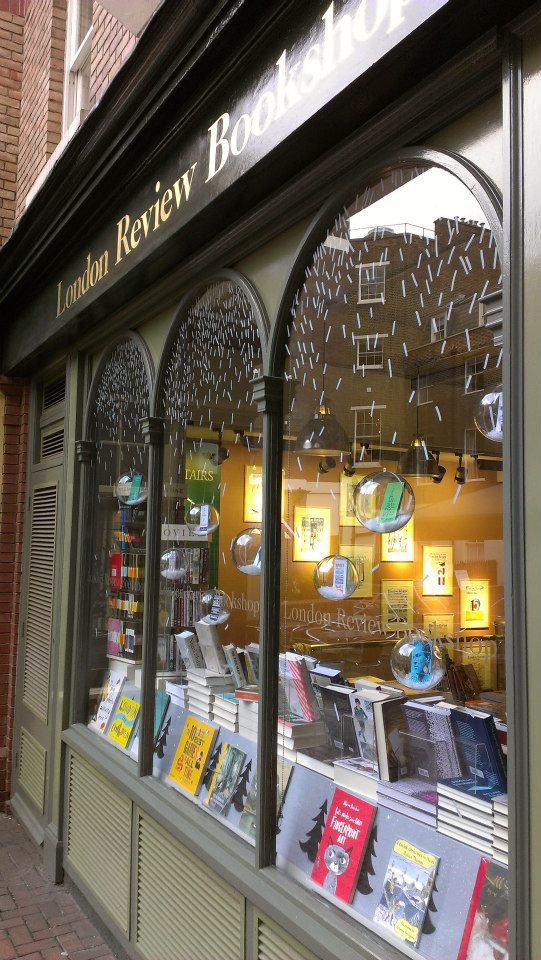

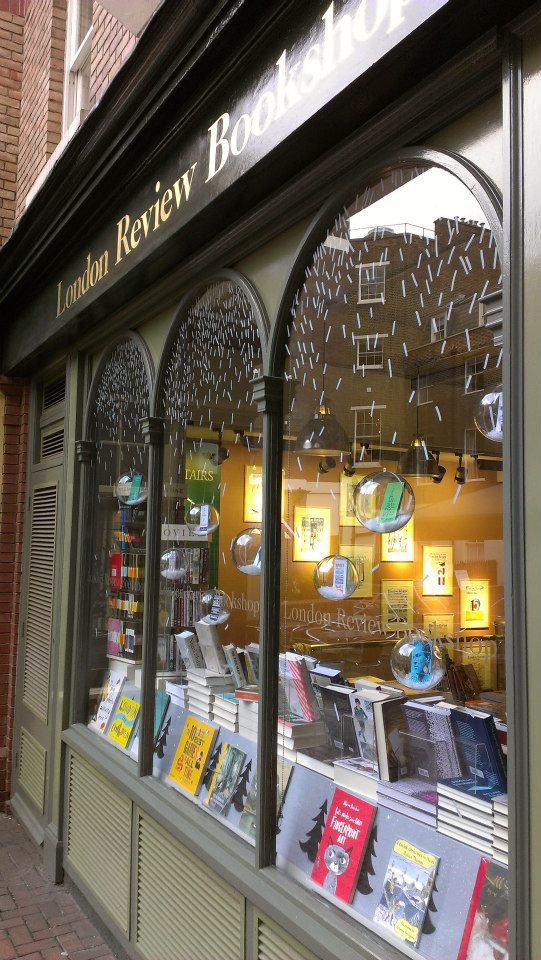

The event was sold out and crammed into the LRB bookshop on Bury Lane, which were already with crammed with books.

Until recently, Krasznahorkai was better known by reputation than by output in the West. Susan Sontag called him “the contemporary Hungarian master of apocalypse who inspires comparison with Gogol and Melville.” W. G. Sebald said, “The universality of Krasznahorkai’s vision rivals that of Gogol’s Dead Souls and far surpasses all the lesser concerns of contemporary writing.”

Satantango, first published in Hungary in 1985 and now regarded as a classic, was finally published in English this year, translated by the Hungarian-born English poet and translator George Szirtes.

“I had to write only this book and no more. You try to write only one book and put everything you want to say in one book, to create my own literary world with my sentences,” Krasznahorkai told last week’s audience.

The Irish Tóibín made a stab at describing Krasznahorkai’s style, which he saw as “removing the need for objects in novel and seeing whether a novel can live in a different space.”

Tóibín described the novel as “a secular space,” yet this one “deals with spiritual questions rather than material questions.” God “interferes” with the novel and its characters.

“Bringing God into the novel, it’s dynamite,” Tóibín said. Comment?

The Hungarian Krasznahorkai demurred. “Hmmmm,” he said. Then again, “Hmmmm…” Finally, he concluded, “The question is wonderful, but I couldn’t answer. It’s too difficult for me. I’m not that clever.”

Maybe Tóibín should have read last August’s Guardian article for a clearer, post-communist spiritual statement from Krasznahorkai:

He gestures to the computer sitting on the table at his elbow. “This is the result of 10,000 years? Really? We have microphone, laptop, this technical society – that’s all? This is sad, and very disappointing. After so many geniuses in the human story from Leonardo to Einstein, from the Buddha to Endre Szemerédi, these are fantastic figures, and their work is unbelievably important and we cannot do anything with it – why?”

According to the LRB website touting the event, he remains an optimist: “You will never go wrong anticipating doom in my books, anymore than you’ll go wrong in anticipating doom in ordinary life.”

Krasznahorkai was born in Gyula, close to the Romanian border. Tóibín quoted Auden saying that a writer’s childhood should have as much neurosis as a child can take. “I was absolutely not a normal child,” replied the Hungarian writer.

“I chose that.”

For awhile, he lived in a village in the countryside “very far from Budapest, very far from the next village,” a place that was filled with “houses with peasants and tiers,” he said, switching briefly to German to refer to the cows and livestock that cohabit the spaces. “Rain and an absolutely hopeless sky. … no heaven, no questions about heaven. Only how can I drink the next pálinka? What can we eat?”

“I had the feeling that this kind of people only lived down below. They were not 30 or 60 years old, but 6,000 years old, without names. Everyone was the same, every fate was the same – like rain. A drop came down, and then another.”

“I chose that. I was 19 years old.” He compensated by reading Dostoevsky, Dante, and ancient Greek literature.

Before 1989, he said, “Hungary was an absolutely unreal, crazy country. Abnormal and unbearable. After 1989, it became normal and unbearable.” In what he called “Old Hungary,” there was “very big misery – the mood was unbelievably sad and hopeless.”

He’s not worried about finding readers. “Most of us need only ten, maybe six on a bad day,” Tóibín agreed.

He knows his place.

George Szirtes was in attendance (in fact, it was the night before our talk at the British Academy), and the affable translator was invited up to the podium for a few words:

“It was slow. I had headaches regularly,” he said describing the process of translating Krasznahorkai’s work. He thought it would take a year and a half. It took four. His first words on meeting Krasznahorkai were an apology. Not to worry, said Krasznahorkai, “it took me six years to write.”

As he’s translating, Szirtes asks himself, “What is this sentence up to? What is it looking for? … When you turn it into English, what kind of noise is it?” The noise in translation is not the same as the noise in the original: “The noise is distinctly related, but transplanted.”

And, after four years of translation, he tackled Tóibín’s questions: “I know that world more, but it’s a visionary world – a visionary world looking for order. The characters are not looking for God, but looking for their place.”

The session continued with questions from the audience, but Krasznahorkai made a plea to the audience as he asked for questions.

He put his hands together, prayer-like, “Only I beg you, nothing about God.”