The “satiric, terrifying” legacy of poet Weldon Kees

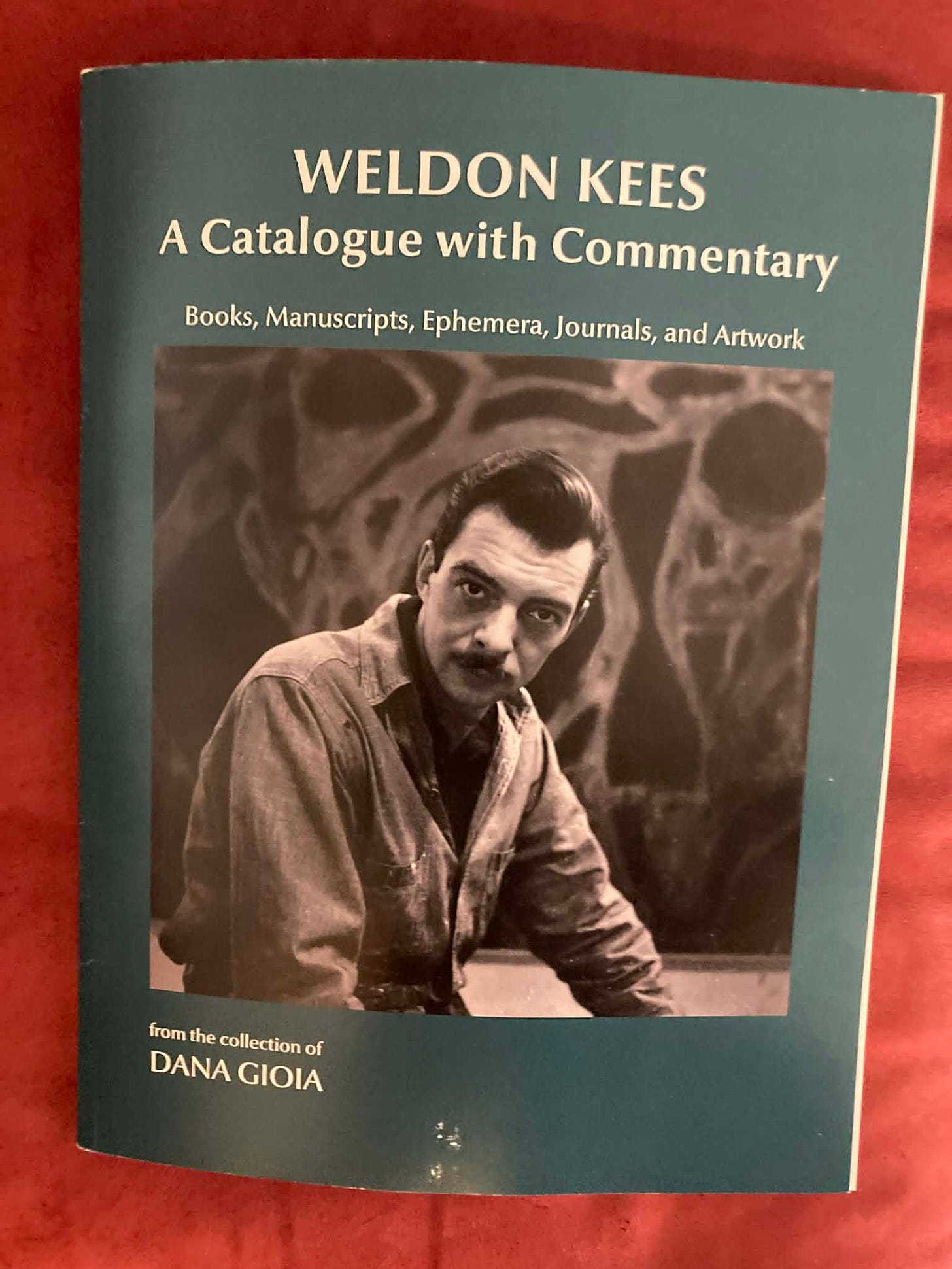

Monday, December 8th, 2025From my mailbox: Dana Gioia, poet and former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, sent me the latest fruits of his labors. Dana has long been a champion of the of the overlooked poet Weldon Kees (1914-1955). According to poet Donald Justice, “Kees is original in one of the few ways that matter: he speaks to us in a voice or, rathre, in a particular tone of voice that we have never heard before.” Dana has just published a catalogue of his own collection with commentary, including works of fiction and non-fiction, broadsides, journals, music and recordings, critical works, and more. Here is the preface:

I first discovered the poetry of Weldon Kees in 1976—fifty years ago—while working a summer job in Minneapolis. I came across a selection of his poems in a library anthology. I didn’t recognize his name. I might have skipped over the section had I not noticed in the brief headnote that he had died in San Francisco by leaping off the Golden Gate Bridge. As a Californian in exile, I found that grim and isolated fact intriguing.

I decided to read a poem or two. Instead, I read them all, with growing excitement and wonder. I recognized that I was reading a major poet. He was a head-spinning cocktail of contradictions—simultaneously satiric and terrifying, intimate and enigmatic. He used traditional forms with an experimental sensibility. He depicted apocalyptic outcomes with mordant humor. I had found the poet I had been searching for. Why had I never heard of him? Embarrassed by my ignorance, I decided to read everything I could find by and about him.

It was a Saturday afternoon. I had the rest of the weekend free. I drove to the main branch of the Minneapolis Public Library, heady with anticipation. I was eager to read all of his books. I also wanted to see what other readers thought about him. I knew my way around libraries—an important skill in those pre- internet days. Whatever books and commentary existed, I would find.

What I found after two days of searching was nothing. There was not a single book of any kind by or about Weldon Kees in the Minneapolis library system. His work, I also discovered, did not appear in standard anthologies. (I had read one of the only two anthologies that had ever featured a large se- lection of his poems.) There was no biography. There were no entries about him in the standard reference works. Nor were there chapters on him in the numerous critical books on contemporary poetry.

He went unmentioned in the biographies of his contemporaries. There had never even been a full-length essay published on his work.

By Sunday evening, I realized why I had never heard of Kees. Hardly noticed during his lifetime, in death he had been almost entirely forgotten. A suicide at forty-one, Kees had succeeded in his last endeavor—vanishing. His body had never been recovered. Kees had been washed away from posterity with- out rites or remembrance. All his work was out of print. Worse yet, most of it—the stories, novels, plays, and criticism—had never been collected. Some of it, such as his first novel, had been lost entirely. Only the poems, a small, brilliant body of work, survived precariously—without criticism or commentary, almost without readers.

I decided then I would write a long, comprehensive essay on his work. It was not the sort of thing I had done before. I could not begin, however, without knowing more. I did not own any of his books. I knew few facts about his life. I began to search, gather, and collect. I not only found books, journals, and eventually manuscripts; I found people who had known and worked with him. I also discovered I was not alone in my intense admiration.

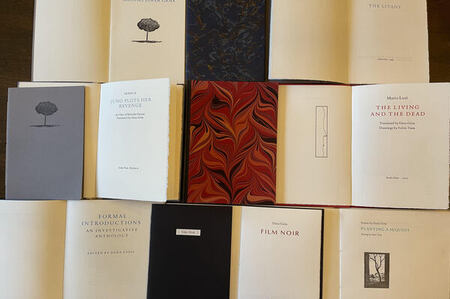

Three years later I published my essay in a special issue of the Stanford literary magazine, Sequoia, edited by my brother [jazz scholar] Ted Gioia. The issue stirred up a surprising amount of interest. I was soon planning an edition of his short stories, which had never been published in book form. That task led me to new material and new people. I had not realized that Kees had been a true polyartist who had not only mastered fiction and poetry, but also painting, photography, filmmaking, and jazz. I kept working on new projects, and the collecting never stopped. His audience also grew, though not among academics. His admirers were writers, artists, printers, and musicians.

This catalogue documents some of what I found in my search for Weldon Kees. It is not a conventional bibliography. It describes a personal collection with commentary. It tries to tell the story of a writer through his books. It evokes Kees’ polymathic imagination from his art, music, and photography. It also reveals the existence of three of his large notebooks which document his prime years as a poet. I wrote this little book mostly for myself and a few friends. I hope it appeals to other readers, writers, and collectors. If this book is for you, you’ll know it.

Find some of Weldon Kees’s poems at the Poetry Foundation here.