Carl Proffer snapped a photo of Joseph Brodsky with Ellendea outside Leningrad’s Transfiguration Cathedral in 1970. (Photo copyright: Casa Dana)

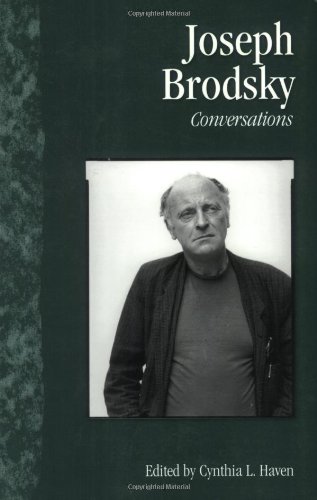

Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky, exiled from the Soviet Union in 1972, has inspired a number of memoirs since his death. One big one was missing, until a few weeks ago.

Ellendea Proffer Teasley‘s Brodsky Among Us is now in its third printing, although it was released only last month in Russia by Corpus, one of the largest publishers in Russia. Reviews have been laudatory – and the book quickly shot to the top ten at the main Moscow bookstore, Moskva. The author is now on her triumphant tour of Russia, giving talks, media interviews, book signings, press lunches, and photo ops. With her late husband, Carl Proffer, she co-founded the avant-garde, U.S.-based Russian publishing house Ardis during the Cold War. Together, they brought Brodsky to America.

The literary acclaim has caught Ellendea off-guard. Russians generally like their poets stainless, and her memoir is as candid as it is affectionate. Her Brodsky is brilliant, reckless, and deeply human. “I did not expect the response I’m getting,” she wrote to me. “It is so moving to me. They understood exactly what I was doing, and they are grateful that it’s not more myth-making.”

The literary acclaim has caught Ellendea off-guard. Russians generally like their poets stainless, and her memoir is as candid as it is affectionate. Her Brodsky is brilliant, reckless, and deeply human. “I did not expect the response I’m getting,” she wrote to me. “It is so moving to me. They understood exactly what I was doing, and they are grateful that it’s not more myth-making.”

While I have been encouraging her to write a memoir for years, I had not seen enough of her writing to anticipate what such a work would look like. Frankly, I did not expect anything of this caliber – an engaging, compulsively readable text that is bodacious, graceful, seamless. Perhaps I should not have been surprised: five years after Carl’s untimely death in 1984, she received a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in her own right. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, she has kept a low profile; this book marks her powerful comeback as a major figure in Russian literature.

The Proffers befriended Brodsky (1940-1996) in Leningrad. When the U.S.S.R. gave him the heave-ho, the couple miraculously secured an appointment for the unknown foreigner as poet-in-residence at the University of Michigan, which launched his career in the West. In Brodsky Among Us, she writes of the first encounter in the present tense, as if it were still replaying in her head, over and over:

“The most remarkable thing about Joseph Brodsky is his determination to live as if he were free in the eleven time zone prison that is the Soviet Union. In revolt against the culture of ‘we,’ he will be nothing if not an individual. His code of behavior is based on his experience under totalitarian rule: a man who does not think for himself, a man who goes along with the group, is part of the evil structure itself.

Joseph is voluble and vulnerable. He brings up his Jewish accent almost immediately; when he was a child his mother took him to speech therapy to get rid of it, he says, but he refused to go back after one lesson. He is constantly qualifying whatever he has just said, scanning your reactions, seeking areas of agreement. He talks about John Donne and Baratynsky (both poets of thought) then says da? to see if you agree. (Later he would use Yah? this way in English.) This is part of his social courtship pattern. Of course there is another Joseph, the one who doesn’t like you, and that Joseph – whom we rarely see, but are often told about – is insolent, arrogant and boorish. I am reminded of what Mayakovsky‘s friends said about him – that he had no skin.”

She explains the combativeness later, “He needed his enemies; resisting them – and the state – had formed his identity.” Hence also his careerism, his relentless (and astonishingly successful) social climbing among the New York City literati: “If you had fame, you had the power to affect a culture; if you had fame you were showing the Soviets what they had lost,” she wrote.

Much of the current Russian attention is not just on Brodsky, but on the Cold War legacy of Ardis itself, given that censorship levels in Russia are returning the nation to the 1970s. Journalist Nikolai Uskov, who has visited the Ardis archives at the University of Michigan, is working on a big book about the courageous publishing house that operated out of an Ann Arbor basement.

On Russian TV with Ksenia Sobchak (Photo: Casa Dana)

I met Ellendea back at the University of Michigan in the 1970s and visited her and Carl at the former country club that had become the Proffer family home and base of operations. Together, the Proffers published the best Russian literature at a time when the U.S.S.R. wasn’t. As I wrote a dozen years ago:

The competition was admittedly limited: Soviet publishers were hamstrung in what they could print; they weren’t publishing much that was new, let alone groundbreaking. The emigre YMCA press in Paris (which published Solzhenitsyn, among others) and Possev in Germany had a religious or political bent, a bias that often alienated younger writers. Samizdat was one alternative: haphazard, handwritten or mimeographed, and highly perishable.

Then there was Ardis. With its related venture, the innovative Russian Literature Triquarterly, Ardis brought Western readers to Russian writers. Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, Velimir Khlebnikov, Mikhail Bulgakov, even Anna Akhmatova were relatively little known in the era before Ardis set up shop; their works were suppressed, their names and reputations were inevitably jumbled with a plethora of lesser, officially approved writers.

Her memoir is likely to cement the Ardis legacy in the best possible way. Brodsky Among Us is compelling, polished, pitch-perfect. She captures his restless self-reinvention, the bluster, the belligerence, the boorishness – while never losing sight of his tenderness and generosity, the reason so many, including Susan Sontag as well as the author, forgave him everything. This is, above all, a loving memoir.

Signing books at the Dostoevsky Library (Photo: Casa Dana)

Brodsky Among Us is about as flawless a book as one could expect. I wished it wouldn’t end. I found myself marking passages I wanted to return to, sentences I wanted to remember. It’s short, but it’s not a bad idea to leave the reader wanting more. I suspect she leaves out all the right things. While some Russian readers have noted the book’s understatements and omissions, I know that she was anxious, first and foremost, that the poet’s oeuvre not be overshadowed by the anecdotes.

Recently, Russian government has attempted to appropriate its rejected poet. Brodsky’s words were featured in the closing ceremonies of the 2014 Sochi Olympics, a startling move to reclaim the writer who would not have survived had he stayed, and may not have thrived under today’s Russian regime, either. Brodsky never returned to his beloved Petersburg. Why? In part, Proffer writes, because he didn’t believe anything had really changed. She writes: “Joseph had many stated reasons for not going back. He said different things, depending on his time and mood, so all one can really trust are his actions. He did not return to his native country when he could have. I know a few of his reasons: one was the iron conviction that return would be a form of forgiveness … Exile was so difficult that it was hard to believe one could just go back as if it had not cost you anything. As Americans descended from immigrants, we are familiar with this phenomenon: sometimes you love your country but it doesn’t love you back. This loss becomes a part of your new identity.”

Ellendea on air at Radio Echo Moscow (Photo: Casa Dana)

The back cover of Brodsky Among Us has an attention-grabbing quote, but out of context one that sounds misleadingly harsh. Here are the paragraphs that goes around that quotation, which addresses the poet’s posthumous revision:

“There is a Brodsky stamp in America, and there is an Aeroflot plane named after him. I don’t want there to be a museum for Joseph, I don’t want to see him on a stamp, or his name on the side of a plane – these things mean that he is dead dead dead dead and no one was ever more alive.

I protest: a magnetic and difficult man of flesh is in the process of being devoured by a monument, a monstrous development considering just how human Joseph was.

Joseph Brodsky was the best of men and the worst of men. He was no monument to justice or tolerance. He could be so lovable that you would miss him after a day; he could be so arrogant and offensive that you would wish the sewers would open up under his feet and suck him down. He was a personality.

The poet’s destiny was to rise, like his autumn hawk, into that upper atmosphere even if it was going to cost him everything.”

Eminent translator Viktor Golyshev, Ellendea Proffer Teasley, and critic Anton Dolin at standing-room only event. (Photo: Casa Dana)

When Proffer, who had relocated to southern California, sold Ardis to Overlook Press in 2002, I wrote about the transition in the TLS, and the Los Angeles Times Book Review was so eager to republish the piece they tracked me down to a secluded beach in Ocho Rios to get my permission to reprint tout de suite. Those were the days when newspapers still had cutting-edge book review sections willing to take a risk, the LATBR foremost among them. In 2015, publishers are looking at markets, not enduring legacies, and book editors don’t take too much interest in what happens beyond their shores. C’est dommage.

Here’s why this story is important here, now: most of his poetic career was in the U.S., not Russia. Previously published memoirs by Lev Loseff (I wrote about it for Quarterly Conversation here) and Ludmila Shtern (I wrote about it in the Kenyon Review here) are greatly illuminating, but shortchange his American life. The American story is one the Russians didn’t know, and the one that we haven’t told, spotlighting the auto-didact’s wondrous, rough-and-tumble self-reinvention, admittedly marred by the ambitious, ill-advised self-translations that would have torpedoed a lesser genius. He became the first foreign-born U.S. Poet Laureate. He taught generations of American students – including this one. Those of us who knew him will never forget him – those who didn’t, especially, need this book. Although the champagne corks are popping in Russia, most of Brodsky Among Us takes place on this side of the world – it’s an American story, about an American career. He is one of us.

Brodsky Among Them: The Proffers & the poet at Mark Hopkins Hotel, San Francisco, 1972. (Photo copyright: Casa Dana)

I had met Joseph Brodsky a few years before at the Etkinds’ place in Leningrad. I was there with our daughter Mirli; she must have been three years old. I had put her to sleep on a couch in the living room. (No one would expect that a Soviet university professor had a guest room!) So: Brodsky came in, beaming with happiness because on this day his son was born. We all congratulated him. Mirli could not think of sleep after this and flirted with Joseph. He, in a good-natured way, flirted back.

I had met Joseph Brodsky a few years before at the Etkinds’ place in Leningrad. I was there with our daughter Mirli; she must have been three years old. I had put her to sleep on a couch in the living room. (No one would expect that a Soviet university professor had a guest room!) So: Brodsky came in, beaming with happiness because on this day his son was born. We all congratulated him. Mirli could not think of sleep after this and flirted with Joseph. He, in a good-natured way, flirted back. Brodsky and Proffer had dinner with Heinz and Elisabeth Markstein that evening, and they discussed the Brezhnev letter. Carl Proffer’s memories: “Markstein said he should publish the letter, but Joseph said ‘No, it was a matter between Brezhnev and me.’ Markstein asked, ‘And if you publish it, then it’s not to Brezhnev?’ And Joseph said, yes, precisely. The Marksteins were very kind, and they offered the services of their young daughters to show us both around Vienna. But for the most part we were on our own, and since for the first time we were spending a great deal of time together alone, we talked a lot, especially at night.” (The Brezhnev letter, or one version of it, is included in the new Stanford collection – I wrote about that

Brodsky and Proffer had dinner with Heinz and Elisabeth Markstein that evening, and they discussed the Brezhnev letter. Carl Proffer’s memories: “Markstein said he should publish the letter, but Joseph said ‘No, it was a matter between Brezhnev and me.’ Markstein asked, ‘And if you publish it, then it’s not to Brezhnev?’ And Joseph said, yes, precisely. The Marksteins were very kind, and they offered the services of their young daughters to show us both around Vienna. But for the most part we were on our own, and since for the first time we were spending a great deal of time together alone, we talked a lot, especially at night.” (The Brezhnev letter, or one version of it, is included in the new Stanford collection – I wrote about that  The Viennese Markstein spent her childhood in Switzerland, Moscow, and Prague. She was expelled from the Communist Party and barred from the Soviet Union in 1968 (according to German Wikipedia) when she was discovered smuggling letters of

The Viennese Markstein spent her childhood in Switzerland, Moscow, and Prague. She was expelled from the Communist Party and barred from the Soviet Union in 1968 (according to German Wikipedia) when she was discovered smuggling letters of