Carl and Ellendea Proffer with Joseph Brodsky in Ann Arbor, circa 1974.

Today would have been Nobel poet Joseph Brodsky‘s 77th birthday. We’ll celebrate with a note from his friend, Ellendea Proffer Teasley, co-founder of Ardis Books with her late husband, Prof. Carl Proffer of University of Michigan. Ellendea has just returned from another triumphant tour of Russia, where she is being treated like a goddess. The Proffers ran a publishing house that published the best of Russian literature when the Soviet houses did not. Now Russians are turning to her to learn a chunk of their own literary history. She is speaking to standing-room-only gatherings.

Ellendea speaking at the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg.

A few months ago she made a tour for Brodsky Among Us, newly published by Corpus. Now she is on tour for the publication of Carl Proffer‘s 1983 Widows of Russia, newly translated and published in Russia – and selling very, very well. The book describes the Proffers’ meetings in Soviet-era Russia with the great literary widows of Russia, including Lily Brik and Nadezhda Mandelstam. It also includes Carl’s unfinished memoir of Joseph Brodsky (he died of cancer in 1984). His book being widely quoted on the internet. While others have written about Madame Mandelstam and Madame Brik and others since Carl’s memoir, she tells them, “Read it, to see the character of the man who was so important to your culure.”

Her message: “Do not make idols of people.” In today’s Russia, she told me, Joseph Brodsky is providing a model in how to resist censorship, and even outright oppression. Of course she speaks Russian fluently.

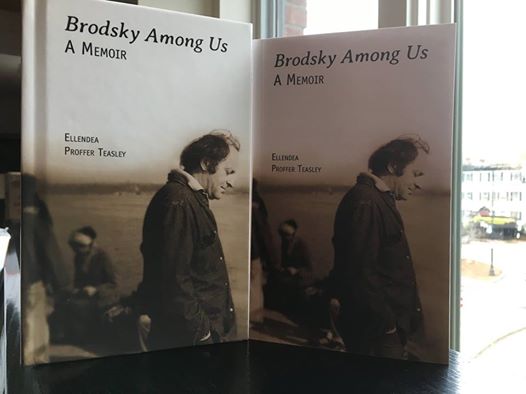

Here’s another bit of good news: Ellendea’s Brodsky Among Us, a runaway bestseller in Russia, is in English at last. Here is a blurb on the back cover from an excellent article in The Nation: “Ellendea Proffer Teasley, in her short new memoir [Brodsky Among Us] offers a different view of the poet. It’s an iconoclastic and spellbinding portrait, some of it revelatory. Teasley’s Brodsky is both darker and brighter than the one we thought we knew, and he is the stronger for it, as a poet and a person. . . Brodsky Among Us appears to have been written in a single exhalation of memory; it is frank, personal, loving, and addictive: a minor masterpiece of memoir, and an important world-historical record.” (Let me dissemble no more, gentle reader, it is Humble Moi who wrote the Nation article. You can read the whole thing here.)

I opened the English edition at random, and ran across this passage:

On Joseph Brodsky’s first morning in the United States I came downstairs to find a bewildered poet. He held his head with both hands and said: “Everything is surreal.”

It was surreal for me as well. Here he was in our little townhouse decorated in seventies style—wall-to-wall carpet, a “Mediterranean” couch, and my mother-in-law’s dining set, now used as a conference table.

“I got up this morning,” he said, humor mixing with alienation, “and I see Ian sitting on the kitchen counter. He puts bread in a metal box. Then the toast pops up by itself. I don’t understand anything.”

“I got up this morning,” he said, humor mixing with alienation, “and I see Ian sitting on the kitchen counter. He puts bread in a metal box. Then the toast pops up by itself. I don’t understand anything.”

He had arrived at Detroit airport the day before, straight from London and his first meetings with famous British poets. And now he was here in Ann Arbor, which in no way corresponded to his imaginings; he really was like that literary frog who woke up and found he was in the Gobi Desert. Like many émigrés, he had imagined this country to be like his minus all the bad things. Nothing could have prepared him for the strangeness of this town, and the place he would occupy in it.

He later said, he came to be glad that his start was in Ann Arbor rather than New York, because he had time to adapt and get his English up to speed. Nonetheless, the early days were difficult for him, his eye could not get used to the scale of a university town of 100,000 (30,000 of them students at the University of Michigan). Soviet Russia was a centralized universe, with only two cities that mattered. America had many centers of power, and some of them looked like this town. He was intelligent enough to understand that he had entered a culture of low-context. The only thing unifying the diverse world of Americans was popular culture, and even that was weaker than centrally-controlled Soviet propaganda.

Ann Arbor would be Joseph’s home base until 1981; he would come back often even after moving away, always warmly welcomed. Joseph complained to Russian friends in the beginning that Ann Arbor was a desert, but actually it was something far, far worse: it was where he was forced to learn many new things, sometimes against his own inclinations. We taught him how to live independently in America—opening a bank account, writing checks, buying food, driving—and it was hard for him, he had no wife or mother to see to these things. All he had was us, and we were both working full-time, so he had to learn quickly.

Ellendea interviewed at Moscow art museum.

Teaching Joseph how to drive was a Pninian experience, full of risk and comedy. An epic could be written about the number of people who took him for the driving exam (I think he failed the written test five times); he wanted to cheat but Carl wouldn’t let him—then he was ashamed he had wanted to. He had some spectacular accidents (once he jumped a median strip and ended up facing the wrong way), but he managed not to hurt himself or others.

Ann Arbor was the place he came to the full realization that he would not see his country again. Joseph had left his parents behind and now they were hostages, one of the many reasons he indulged in no direct political activity. (His two children—Andrei Basmanov and Anastasia Kuznetsova, the daughter of the ballerina Maria Kuznetsova)—did not have his last name, so they were somewhat safer.) Joseph missed his family, he was used to living in that tiny room carved off from theirs. On the other hand, he felt freer than he ever had in his life. (I recognized him in Bellow’s comment that only in America did the Jewish sons get to leave their parents’ houses.)

He was not cut off from his world in Leningrad: friends and scholars ferried letters, money and presents to them and information and letters back. There was always someone going or coming, including us, and there were many friends in Leningrad checking up on his parents and reporting to Joseph by letter and telephone.

He was not cut off from his world in Leningrad: friends and scholars ferried letters, money and presents to them and information and letters back. There was always someone going or coming, including us, and there were many friends in Leningrad checking up on his parents and reporting to Joseph by letter and telephone.

It took Joseph about six months to people his Michigan world—Russians found him, American poets found him, interested graduate students and other professors found him; he found the girls himself.

He was almost never alone, but he experienced the loneliness of a man surrounded by people yet aware that the context has changed. That loneliness had a special flavor made up of longing and disgust, and can be seen most prominently in his “Lullabye of Cape Cod.” I know that Joseph had experienced this sort of loneliness before emigration, but the change sharpened the experience.

The fear that loneliness forced up from his subconscious is most searingly expressed in “The Hawk’s Cry in Autumn”; when I read this poem from 1975, I understood that the poet was the hawk who dies because has flown too high for survival: “what am I doing at such a height?” he asks himself.

Later Joseph gave interviews in which he talked about the years in Michigan as the only childhood he ever had.

It returned me to his own words on the experience, at a commencement address in 1988: “I’m no gypsy; I can’t divine your future, but it’s pretty obvious to any naked eye that you have a lot going for you. … you’ve been educated at the University of Michigan, in my view the best school in the nation, if only because sixteen years ago it gave a badly needed break to the laziest man on earth, who, on top of that, spoke practically no English – to yours truly. I taught here for some eight years; the language in which I address you today I learned here; some of my former colleagues are still on the payroll, others retired, and still others sleep the eternal sleep int he earth of Ann Arbor that now carries you. Clearly this place is of extraordinary sentimental value for me; and so it will become, in a dozen years or so, for you.”

It returned me to his own words on the experience, at a commencement address in 1988: “I’m no gypsy; I can’t divine your future, but it’s pretty obvious to any naked eye that you have a lot going for you. … you’ve been educated at the University of Michigan, in my view the best school in the nation, if only because sixteen years ago it gave a badly needed break to the laziest man on earth, who, on top of that, spoke practically no English – to yours truly. I taught here for some eight years; the language in which I address you today I learned here; some of my former colleagues are still on the payroll, others retired, and still others sleep the eternal sleep int he earth of Ann Arbor that now carries you. Clearly this place is of extraordinary sentimental value for me; and so it will become, in a dozen years or so, for you.”

Happy birthday, Joseph.

The Proffers with the future Nobel poet, San Francisco, 1972.

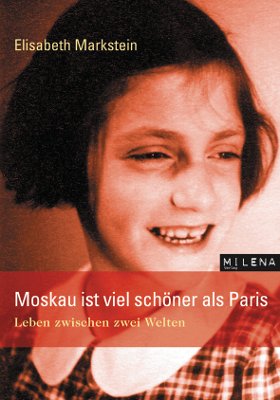

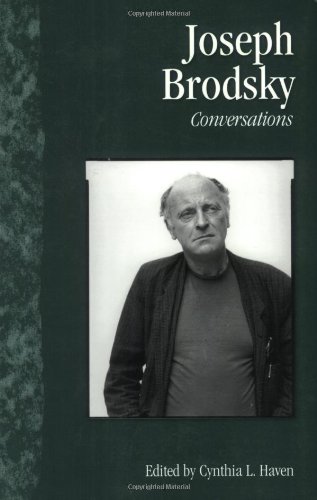

Marat Grinberg writes about

Marat Grinberg writes about

He was not cut off from his world in Leningrad: friends and scholars ferried letters, money and presents to them and information and letters back. There was always someone going or coming, including us, and there were many friends in Leningrad checking up on his parents and reporting to Joseph by letter and telephone.

He was not cut off from his world in Leningrad: friends and scholars ferried letters, money and presents to them and information and letters back. There was always someone going or coming, including us, and there were many friends in Leningrad checking up on his parents and reporting to Joseph by letter and telephone. It returned me to his own words on the experience, at a commencement address in 1988: “I’m no gypsy; I can’t divine your future, but it’s pretty obvious to any naked eye that you have a lot going for you. … you’ve been educated at the University of Michigan, in my view the best school in the nation, if only because sixteen years ago it gave a badly needed break to the laziest man on earth, who, on top of that, spoke practically no English – to yours truly. I taught here for some eight years; the language in which I address you today I learned here; some of my former colleagues are still on the payroll, others retired, and still others sleep the eternal sleep int he earth of Ann Arbor that now carries you. Clearly this place is of extraordinary sentimental value for me; and so it will become, in a dozen years or so, for you.”

It returned me to his own words on the experience, at a commencement address in 1988: “I’m no gypsy; I can’t divine your future, but it’s pretty obvious to any naked eye that you have a lot going for you. … you’ve been educated at the University of Michigan, in my view the best school in the nation, if only because sixteen years ago it gave a badly needed break to the laziest man on earth, who, on top of that, spoke practically no English – to yours truly. I taught here for some eight years; the language in which I address you today I learned here; some of my former colleagues are still on the payroll, others retired, and still others sleep the eternal sleep int he earth of Ann Arbor that now carries you. Clearly this place is of extraordinary sentimental value for me; and so it will become, in a dozen years or so, for you.”

I had met Joseph Brodsky a few years before at the Etkinds’ place in Leningrad. I was there with our daughter Mirli; she must have been three years old. I had put her to sleep on a couch in the living room. (No one would expect that a Soviet university professor had a guest room!) So: Brodsky came in, beaming with happiness because on this day his son was born. We all congratulated him. Mirli could not think of sleep after this and flirted with Joseph. He, in a good-natured way, flirted back.

I had met Joseph Brodsky a few years before at the Etkinds’ place in Leningrad. I was there with our daughter Mirli; she must have been three years old. I had put her to sleep on a couch in the living room. (No one would expect that a Soviet university professor had a guest room!) So: Brodsky came in, beaming with happiness because on this day his son was born. We all congratulated him. Mirli could not think of sleep after this and flirted with Joseph. He, in a good-natured way, flirted back. The Viennese Markstein spent her childhood in Switzerland, Moscow, and Prague. She was expelled from the Communist Party and barred from the Soviet Union in 1968 (according to German Wikipedia) when she was discovered smuggling letters of

The Viennese Markstein spent her childhood in Switzerland, Moscow, and Prague. She was expelled from the Communist Party and barred from the Soviet Union in 1968 (according to German Wikipedia) when she was discovered smuggling letters of