John Hennessy likes big fat books.

Tuesday, November 12th, 2013

Love’s much better, the second time around: Stanford prez on the joy of rereading books. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

Stanford prez John Hennessy is famously techie, right? Here’s the surprise: the former computer scientist also likes ploughing through the big-hearted, super-retro, thousand-page classics of the 19th century. “I like sagas, a big story plus decades,” he confessed to a good-sized crowd at Piggott Hall last week during an exuberant, free-wheeling talk on “Why I Read Great Literature.” You know the books he means: the kind that gets turned into a year’s worth of BBC Masterpiece Theatre viewing.

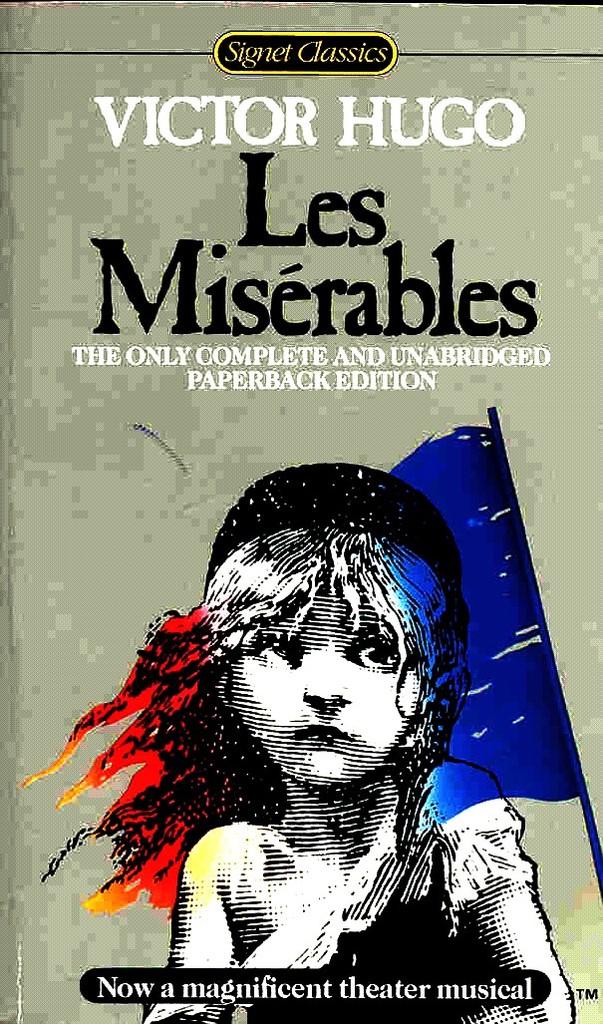

He’s clearly a man after my own heart – he singled out Victor Hugo‘s Les Miserables for particular praise, saying that he’s read the whole shebang several times. This is comforting to me personally, after watching René Girard, that anti-romantic sage and immortel, politely squelch a smirk when I told him of my childhood adoration of the book.

He’s clearly a man after my own heart – he singled out Victor Hugo‘s Les Miserables for particular praise, saying that he’s read the whole shebang several times. This is comforting to me personally, after watching René Girard, that anti-romantic sage and immortel, politely squelch a smirk when I told him of my childhood adoration of the book.

For Hennessy, an apparent turning point in his reading tastes occurred the summer before he entered high school – an over-the-vacation reading assignment that somewhat parallels Stanford’s Three Books program. Clearly one of the books took hold of his imagination: he’s read Charles Dickens‘s A Tale of Two Cities several times since. And although he wasn’t up to reciting the magnificent 118-word opening sentence last week, he did refer to it: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

How many books are enclosed by an immortal first and last sentence? Hennessy had better luck reciting the the famous close: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

Dickens “has proven enough times that I could read anything he writes,” said Hennessy. “He grapples with Victorian England, social injustices, a system that obviously tramples on people.” As for nasty schoolmaster Squeers, in Nicholas Nickleby: “If I ever met him, I would be forced to shoot him,” said Hennessy. These books ask, he said, “How would I have approached that situation? What would I have done?” Now we know. Hennessy would be compelled to commit homicide. Fortunately, fortunately, Squeers must have died in Australia at least a century ago, presumably of natural causes.

Dickens “has proven enough times that I could read anything he writes,” said Hennessy. “He grapples with Victorian England, social injustices, a system that obviously tramples on people.” As for nasty schoolmaster Squeers, in Nicholas Nickleby: “If I ever met him, I would be forced to shoot him,” said Hennessy. These books ask, he said, “How would I have approached that situation? What would I have done?” Now we know. Hennessy would be compelled to commit homicide. Fortunately, fortunately, Squeers must have died in Australia at least a century ago, presumably of natural causes.

Hennessy’s love for Dickens includes the worthy chestnut A Christmas Carol, which he rereads during the holiday season. As for David Copperfield, he gleefully quoted Mr. McCawber; apparently it’s one of his favorite lines: “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen [pounds] nineteen [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.” Well, that’s the techie in him. Throughout the talk he kept presenting numbered lists of thoughts – he likes counting. I always wonder how you know that, when you say you have five points to make, it’s going to stay five points, and not meander into seven. Or you’ll forget one and have only four left. He seems to be good at keeping track.

Like many a young ‘un, he was frogmarched to the great classics. Some books are not wise choices for teenage boys – Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, for example. “I wasn’t up to it. It was too deep, too much angst to it. High school angst is different.”

“An author I was tortured by in high school was Edith Wharton,” he recalled pensively. The inevitable high-school staple, Ethan Frome – it’s mercifully short, after all – was “not the right book for high school guys.” What kid wants to read a tragic story of wasted lives? They say love is much better the second time around – so it seems with these reheated feasts. He’s warmed to Henry James, too, despite a premature exposure to “Turn of the Screw.”

“An author I was tortured by in high school was Edith Wharton,” he recalled pensively. The inevitable high-school staple, Ethan Frome – it’s mercifully short, after all – was “not the right book for high school guys.” What kid wants to read a tragic story of wasted lives? They say love is much better the second time around – so it seems with these reheated feasts. He’s warmed to Henry James, too, despite a premature exposure to “Turn of the Screw.”

I couldn’t agree more with his overall point, but I think the first exposure, however flawed, is important. I’ve just rediscovered Stendhal in a big way after reading it in high school and finding it a little too cold-edged and cynical for my delicate teenage sensibilities. It didn’t help that the class was reading it, for the most part, in French (we all cheated and found translations, of course – I now find it amusing that we thought Mademoiselle Vance didn’t expect us to do this). René Girard definitely approves of this late-life conversion to Stendhal. I’ll have to have another go at Rabelais now, too. These classics, reread at ten-year intervals, resonate within us at different layers of experience, but you do need a prime coat.

Hennessy’s passion is not restricted to Golden Oldies, or reheated feasts from early class assignments – he included some more recent fare in his endless list. “Sometimes fiction is better at telling a story than non-fiction,” he said, citing this year’s Pulitzer prizewinning book, The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson (we’ve written about it here and here and here and, oh, lots of other places). He also cited Arundhati Roy‘s The God of Small Things and Aravind Adiga‘s White Tiger, which helped prepare him for trips to India a few years ago. Where does he get the time? Clearly, he doesn’t watch TV – I wrote about that here.

Sepp Gumbrecht, author of In Praise of Athletic Beauty, offered what he called “the biggest compliment” to Hennessy: “I did not anticipate half an hour when I would not think about football.” He praised Hennessy for taking a firm departure from clever literary theory and speaking with “unbridled and deliberately naïve enthusiasm” about books. He noted the words and phrases Hennessy used most frequently in his talk (apparently, he was counting, too, which would certainly keep his mind off football): 1) redemption, redeeming; 2) tragedy, justice; 3) sacrifice, vengeance. It doesn’t get better than this, does it?

Sepp Gumbrecht, author of In Praise of Athletic Beauty, offered what he called “the biggest compliment” to Hennessy: “I did not anticipate half an hour when I would not think about football.” He praised Hennessy for taking a firm departure from clever literary theory and speaking with “unbridled and deliberately naïve enthusiasm” about books. He noted the words and phrases Hennessy used most frequently in his talk (apparently, he was counting, too, which would certainly keep his mind off football): 1) redemption, redeeming; 2) tragedy, justice; 3) sacrifice, vengeance. It doesn’t get better than this, does it?

Well yes, it does. Hennessy didn’t forget the slash-and-burn, blood-and-guts classics, Homer’s Iliad and Dante’s Inferno.

Well yes, it does. Hennessy didn’t forget the slash-and-burn, blood-and-guts classics, Homer’s Iliad and Dante’s Inferno.

And what does he read at the end of the day, before bedtime? “Junk,” he said. Just like the rest of us.

He escaped by a side door during the refreshments – but not before George Brown and I pleaded with him to reconsider the Purgatorio, the only book in the Divine Comedy where time counts for something – which it did for Hennessy, too, clearly, as he rushed to his next appointment.

***

(Photo above has a gaggle of professors – the contemplative head-on-hand at far right belongs to Josh Landy. Next to him with the snowy beard is Grisha Freidin. The ponytail at his right belongs to Gabriella Safran. Next to her (if you leap an aisle) is David Palumbo-Liu in black glasses, and the half-head to his right belongs to Sepp. Humble Moi at far left with the black Mary Janes. Many thanks for the excellent photography from Linda Cicero, which has often graced this site.)