Dana Gioia’s books, manuscripts, libretti are now at the Huntington Library.

Dana Gioia is a man of letters in the time-honored sense of the term, influencing our culture as a poet and essayist, but also as a translator, editor, anthologist, librettist, teacher, literary critic, and advocate for the arts. His correspondence was extensive, and it went on for decades. Hence, his archive is a treasure trove, and though he has had offers from other institutions to acquire it, he wanted his papers to stay in California. Now they will. He has donated his substantial archive to the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, which announced today it had acquired the papers of the poet and writer who served as the chair of the National Endowment for the Arts from 2003–09 and as the California Poet Laureate from 2015–19.

Dana Gioia in L.A. with friend, Doctor Gatsby (Photo: Starr Black)

It is the second large donation he has made in the last year. Last August, he gave to Stanford the large archive of Story Line Press, which he co-founded. The papers are the central archive for the New Formalism movement. The archive includes a number of people who have spent time at Stanford, including Donald Justice, Donald Hall, Christian Wiman, Paul Lake, Annie Finch, and of course Dana himself, among others. Stanford Libraries already holds the archive for The Reaper, so this is a natural pairing with that irreverent journal.

The larger Huntington archive includes correspondence with many of the major poets and writers for the last several decades, including Elizabeth Bishop, Anthony Hecht, Richard Wilbur, Ray Bradbury, Rachel Hadas, Jane Hirshfield, William Maxwell, Thom Gunn, Edgar Bowers, Kay Ryan, Robert Conquest, Julia Alvarez, Thomas Disch, Cynthia Ozick, Donald Davie, Anthony Burgess, John Cheever, J.V. Cunningham, and even some musicians, such as Dave Brubeck. It also includes his own books, manuscripts, and libretti. “Even after I pruned my correspondence, there is a lot of letters – in the tens of thousands,” said Dana.

“When I told my brother Ted that I had made the donation, he commented that I wanted my papers to be at the Huntington because our mother took us there as children. ‘You’re probably right,’ I said. I still remember seeing the elegant manuscript of Poe’s ‘Annabel Lee’ there nearly sixty years ago. It was my first glimpse into that enchanted kingdom by the sea called poetry.”

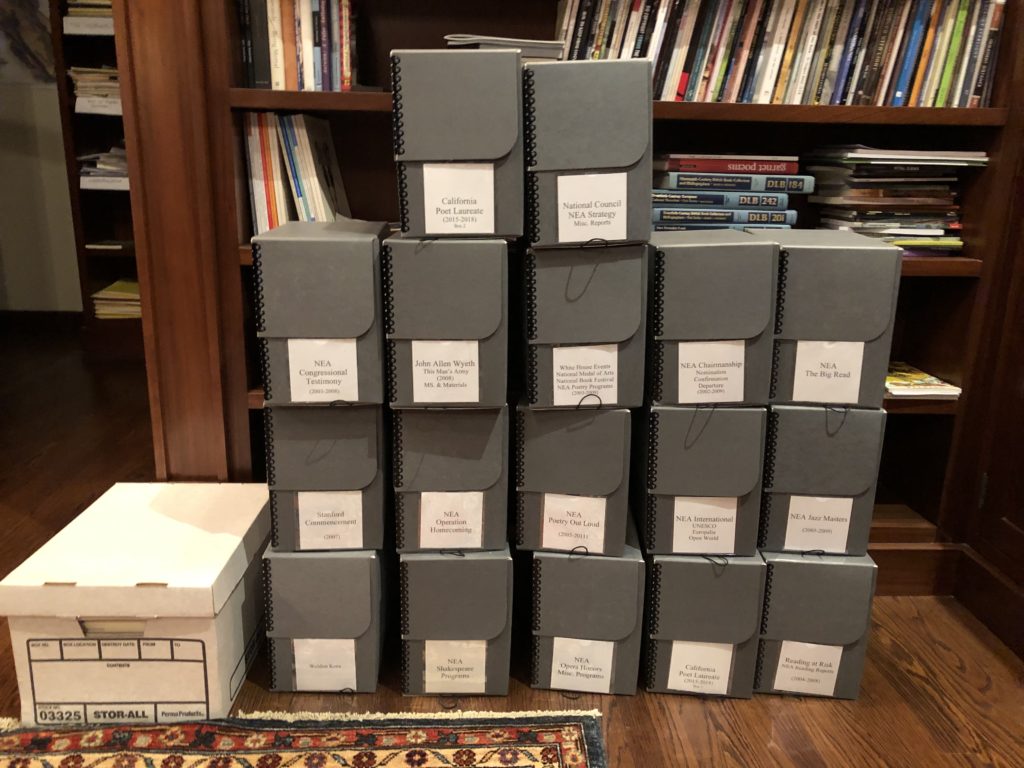

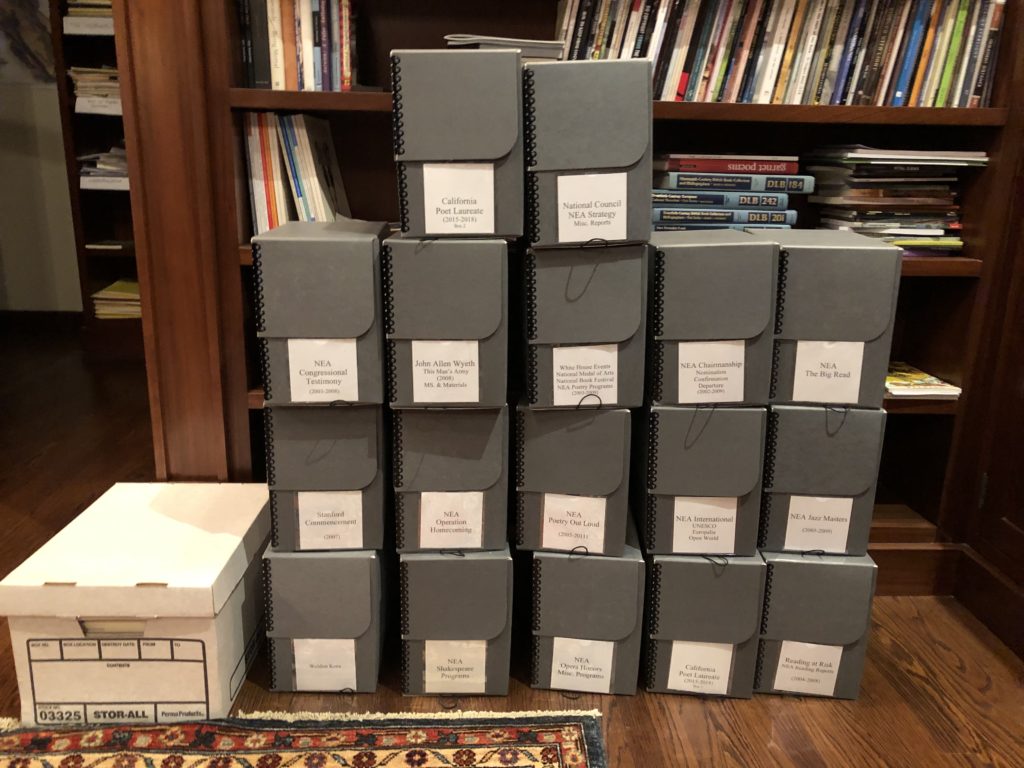

The Huntington picked up 71 archival boxes last December – the first part of his donation. Then Dana Gioia had a more urgent task: the next day he flew back to northern California home, which sustained fire damage during last year’s Kincade wildfire.

From the Huntington release:

The archive documents Gioia’s work as a poet through fastidiously maintained drafts of poems and essays from his books, which include five books of poetry and three books of critical essays. He is one of the most prominent writers of the “New Formalist” school of poetry, a movement that promoted the return of meter and rhyme, although his arts advocacy work situates him in a broader frame.

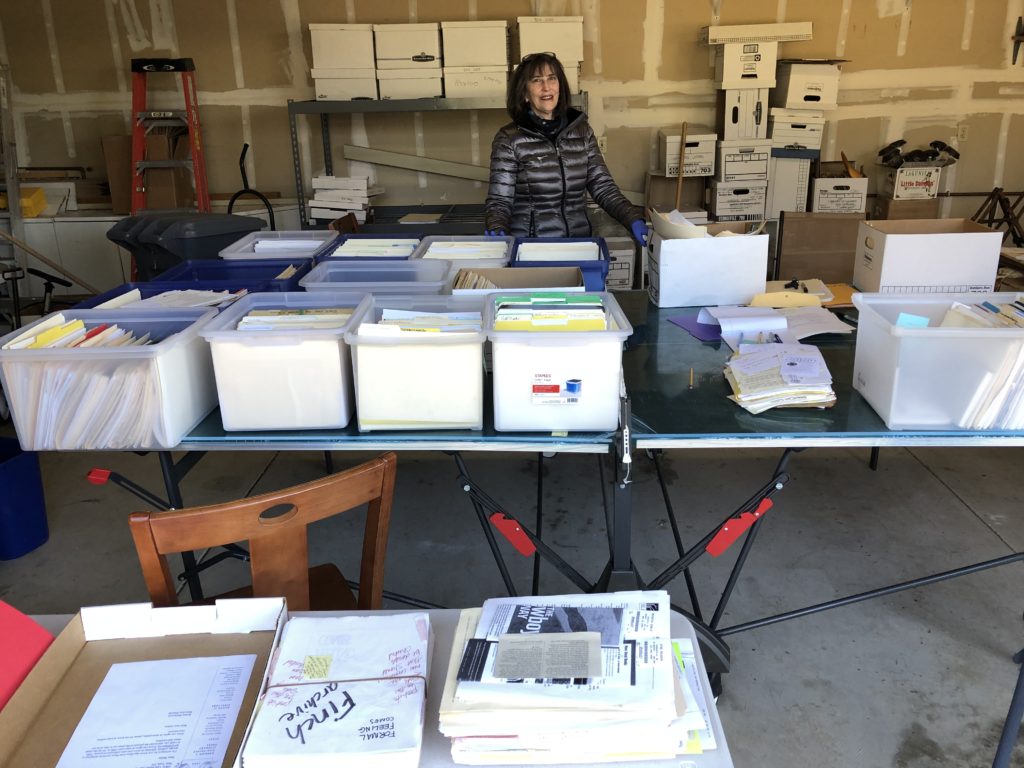

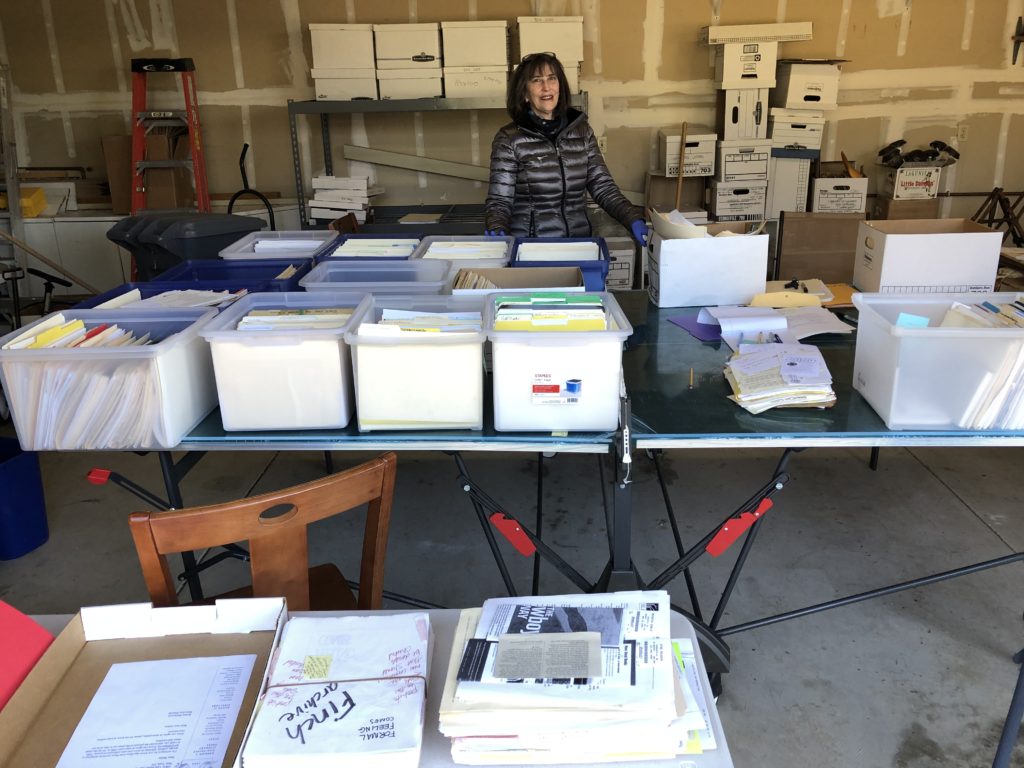

The archive en dishabillé, as Mary Gioia helps organize.

“In his correspondence, you see a writer who has been willing to engage the young and old, the esteemed and emergent—anyone who wants to critically discuss poetic form, contemporary audiences for poetry, and the importance of literary reading during decades when popular culture has become increasingly visual and attention spans have fractured,” said Karla Nielsen, curator of literary collections at The Huntington. “We are delighted that Dana has entrusted his papers to The Huntington, where his collection fits perfectly. He is a local author—he grew up in a Mexican/Sicilian American household in Hawthorne—and even as he attained international recognition as a poet and assumed the chairmanship of the NEA, he remained loyal to the region and invested in Los Angeles’ unique literary communities.”

“I’m delighted to have my papers preserved in my hometown of Los Angeles, especially at The Huntington, a place I have loved since the dreamy days of my childhood,” said Gioia.

While the range of correspondents in the collection is broad and eclectic, the sustained letter writing with poets Donald Justice, David Mason, and Ted Kooser is particularly significant.

Gioia’s work co-editing a popular poetry anthology textbook with the poet X. J. Kennedy from the 1990s to the present will interest scholars working on canon formation during those decades when the “culture wars” were a politically charged issue.

A portion of the materials represent Gioia’s work as an advocate for poetry and the arts at the NEA and as the California Poet Laureate. This work is integral to his career and will be important to scholars interested in the place of poetry and the role of reading for pleasure within greater debates about literacy and literary reading at the beginning of the 20th century. … At The Huntington, Gioia’s archive joins that of another businessman poet, Wallace Stevens; that of a very different but also quintessentially Los Angeles poet, Charles Bukowski; and those of two other New Formalist poets, Henri Coulette and Robert Mezey.

Tens of thousands of letters and much more – now at the library his mother Dorothy Ortiz took Ted and Dana Gioia to visit as children. Dana remembers the Poe manuscript of “Annabel Lee.”