Just like a natural man. (Photo: L.A. Cicero)

Literature is “the living voice of our inner lives.” That’s one reason why, according to Stanford author Robert Pogue Harrison, “when everyone is stumped, invariably we turn to the poets.”

He addressed a small evening crowd at Piggott Hall as part of the “How I Think About Literature” series last week (Stanford prez John Hennessy was the previous speaker; we wrote about his visit here). Though we’ve written about Robert before (oh, here and here and here, among other places), the pleasure never palls. He always presents stuff we didn’t know before and a p.o.v. we hadn’t previously considered.

For example, his discussion this time hinged on the “deponent verb” of ancient Greek, which Robert described as “a verb with an active meaning that takes a passive form.” Hence, the speaker “is not the author or generator of thought.”

“A text like Ovid‘s Metamorphosis thinks me,” he said. The Dante scholar, referring to the Divine Comedy, said that “the whole poem may seem bizarre, medieval, superannuated” even after you study its historical and philological roots. The key is that deponent verb again: “you have to allow it to think you, to recognize yourself in it. … Let the poem do the thinking through me.”

Much of the talk was enjoyably digressive: He added that students must understand the theology of the poem. “I will not be able to read the Divine Comedy in a way that renders it pertinent if I don’t know it’s theology. That’s different than subscribing to the theology that subtends the poem.” Here’s the fun part: he cited Eric Auerbach‘s insistence that, despite its title, The Divine Comedy is a poem of the secular world. Robert noted that “historical individuals pervade it. He’s always on earth – he can’t let it go. Even Paradiso is filled with despair about the state of the secular world.” So true. Robert thought modern readers would have a natural affinity with Paradiso, “if there’s anything most present in the world, it is religious intensity.” (Funny, he said to a class a few years ago that “we live in the Infernal City.” Robert must be having a good year – here’s one reason why.)

He’ll do the thinking, thank you very much.

Back to deponent verbs: No surprise that the author of Forests: The Shadow of Civilization and Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition says that “nature does most of my deep thinking,” and that this particular muse is understandably gagged and silent in a place like New York City (except for Central Park). Nevertheless, “literature thinks me in a way that nature doesn’t.”

“Literature is a response to the injunction of the Delphi oracle, ‘Know thyself,’” he said. Literature is a “crusade of self-knowledge.” A book such as Emma Bovary, he said, teaches us “how much more in us than circumscribed by egos or identities.”

“Philosophers do not illuminate much, but literary authors do,” said Robert, who is a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books. “I believe that literature knows what philosophy attempts,” and reveals it “in a compelling and full-bodied way.”

He ought to know. He has deep roots not only in literature but in philosophy, since he says he was steeped in Martin Heidegger as a student. He also had a chance to see firsthand the inhibiting effect of philosophy as as a student at a “very Derridian” Cornell in the 1980s, as fans of the French philosopher duked it out with the aficionados of the school of hermaneutics. The domination of Derridian discourse gave him a sense of “claustrophobia … a closed indoor room where verbal games were being staged. … The verbal choreography did not excite me as much as it excited my peers and professors.”

He said that the movement Jacques Derrida fostered was “the quintessential academic enterprise,” an observation confirmed “by the fierce determination and lengths it went to secure and hold onto institutional power, especially in the U.S.”

“For me, I wanted literature to remain an adventure … new encounters that were utterly singular.” For that reason among others, he said, “I don’t practice literary theory – I always resisted it as a graduate student.” He said you won’t find a literary theory promulgated in his books. “Where it fails is that it does not provide a model for emulation. That can do students a disservice” because he offers no tools to apply or replicate his line of thought.

The problem with literary theory, he said, is that literary theorists know in advance what they’re going to find, even though “animosity toward theory can blind you.” He added that “there’s a lot of confusion in graduate schools that doing theory is a way of doing philosophy … it’s a very sorry way of doing philosophy, because it’s not embedded in the discipline.”

Derridian games

Most of the talks in the “How I Think About Literature” series have been monologues. But Robert sat on a stool and chatted with grad student Dylan Montanari, who doubles as Robert’s production manager for his popular radio show, “Entitled Opinions.” We always complain about boringness of lecture format, he said, but we still deal in “deadening monologues” most of the time. “The dialogical format liberates thinking,” he said. “It takes it out of the straitjacket.”

Robert also told us a little about his forthcoming book, Juvenescence, slated for release later this year by the University of Chicago Press. “The book poses a simple question that has no simple answer: How old are we?” While our cultural age is “the ground of time,” for each of us as individuals, “aging changes perception.” He cited another philosopher, Immanuel Kant, adding that “time is not the same form of intuition in youth as in age.”

Giacomo Leopardi, too, wrote about how things appear differently to perception with age. Youth perceives the “infinite promise in nature – but nature is unspeakably cruel,” said Robert. Hence, Leopardi lamented to nature: “Why do you deceive your children so?”

“Literature defines the laws of chronology,” he added, which gives us a chance to get our own back. “Where does the future reside in a text? What is still unspoken and unthought?” he asked. “Literature is much more pregnant with the unspoken than philosophy” which “doesn’t have and many pockets of futurity.”

“The whole history of poetry is about age, but not about inhabited age,” Robert said. “Poetry offers an abundance of phenomenological insight.” The child is father to the man – a cliché – but Wordsworth took it to an offbeat conclusion: that the adult is dependent upon, and answerable to, the child that accompanies it throughout life.

He used Gerard Manley Hopkins poem to a young child, “Spring and Fall” as illustration. And just because it’s public domain (and also because it’s beautiful), we’ll use it to conclude this loosely strung concatenation of quotes and thoughts from one of our favorite Stanford maestros.

Long light from a short wick.

Spring and Fall

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow’s springs are the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What héart héard of, ghóst guéssed:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

The desire to find scapegoats and to invest individuals – whether women, ethnic minorities, Nazi collaborators or modern power figures – with the murderous guilt of an entire tribe or civilization also produces an “opposite” phenomenon: the sacred anointing of martyrs. “Human society begins from the moment symbolic institutions are created around the victim, that is to say when the victim becomes sacred,” Girard explained. Think Iphegenia and Helen of Troy,

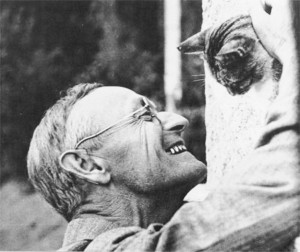

The desire to find scapegoats and to invest individuals – whether women, ethnic minorities, Nazi collaborators or modern power figures – with the murderous guilt of an entire tribe or civilization also produces an “opposite” phenomenon: the sacred anointing of martyrs. “Human society begins from the moment symbolic institutions are created around the victim, that is to say when the victim becomes sacred,” Girard explained. Think Iphegenia and Helen of Troy,  Though he was ultimately elected to the prestigious L’Académie Française, Girard was certainly never as celebrated or as controversial as many of his French contemporaries. Haven therefore deserves much credit for choosing to explore Girard’s life and work. The philosopher drew from a careful study of anthropology, history, and literature to illuminate, even presage the repeat cycles of horror and violence in 20h and 21st century life. And Haven draws important connections between Girard’s work and the salient examples of mob violence and martyrdom creation in America – for example, the murders of blacks during the Civil Rights Era, the attacks of September 11, 2001, the shootings and riots in Baltimore, and lately, the mass beheadings of Americans – on video – by ISIS.

Though he was ultimately elected to the prestigious L’Académie Française, Girard was certainly never as celebrated or as controversial as many of his French contemporaries. Haven therefore deserves much credit for choosing to explore Girard’s life and work. The philosopher drew from a careful study of anthropology, history, and literature to illuminate, even presage the repeat cycles of horror and violence in 20h and 21st century life. And Haven draws important connections between Girard’s work and the salient examples of mob violence and martyrdom creation in America – for example, the murders of blacks during the Civil Rights Era, the attacks of September 11, 2001, the shootings and riots in Baltimore, and lately, the mass beheadings of Americans – on video – by ISIS. A belated postscript to

A belated postscript to