“Even My Revolts Were Brilliant with Sunshine”: The Solar Humanism of Albert Camus

Saturday, July 28th, 2018“THE SUN THAT REIGNED OVER MY CHILDHOOD FREED ME FROM ALL RESENTMENT.”

“If that is justice, then I prefer my mother.”

Those words marked a turning point for French-Algerian author Albert Camus. The context was the Algerian war for independence, which Camus ultimately opposed. He made the statement after revolutionaries began planting bombs on tramways in Algiers, where his mother still lived.

Camus was all for “l’instant.”

Jean-Marie Apostolidès, playwright, psychologist, and French professor at Stanford, and Entitled Opinions host Robert Harrison trace Camus’s long intellectual and spiritual journey, from his impoverished Algerian childhood to the car crash that killed him at the age of 46. It’s the latest podcast up at the Los Angeles Review of Books here.

In particular, they discuss his complex relationship with fellow traveller Jean-Paul Sartre, who was the greater philosopher and the more rigorous thinker of the two, while Camus was the greater writer and perhaps the greater soul. Their conflict fascinates intellectuals in France and around the world to this day.

“Camus’s strong bond with his mother is beyond and sometimes against words,” says Apostolidès. Yet Camus’s own mother never read a word of his many books. She was illiterate, half-deaf, and a speech impediment made it difficult for her to hold a conversation.

Apostolidès notes it would be a mistake to think of Camus’s adult life as serene and happy: he had several alcoholic crises, and his family life was undermined by his promiscuity. Yet his psyche was shaped by his sun-drenched childhood in Algeria, so strongly at odds with the bourgeois French upbringing of Sartre, who attended Paris’s premier École Normale. The Nobel Prizewinning Camus held to “the wisdom of a different tradition,” says Harrison, describing the sensibility of the Mediterranean basin and African that was a world away from the Nietzschean northern temperament of Europe. As a result, Sartre was interested in the arc of history; Camus was interested in l’instant of plays, journalism, theater.

Jean-Marie: “Nature has no lessons.”

“This was the main idealogical divide between the solar humanism of Albert Camus and the militant Marxism of Jean-Paul Sartre,” says Harrison. “For Sartre, history was everything, and those who allied with it had to change the world, at all costs. For Sartre, there’s nothing redemptive in the sun and sea.” Sartre kept his “eyes fixed on the Medusa head of reality.

“That is finally the decisive difference between Sartre and Camus, and the reason why the dustbin of history awaits the one, and not the other.”

“I WAS POISED MIDWAY BETWEEN POVERTY AND SUNSHINE. POVERTY PREVENTED ME FROM THINKING THAT ALL WAS WELL IN THE WORLD AND IN HISTORY; THE SUN TAUGHT ME THAT HISTORY IS NOT EVERYTHING.”

POTENT QUOTES:

Jean-Marie Apostolidès:

“At the end of the line of history, there is death.”

“Nature has no direct lesson to teach us. Therefore our values are relative. Nevertheless, we have to create them.”

“Camus did not want a revolution, but at the same time he did not want to accept the passivity of the bourgeois attitude towards life. So he coined this median way between revolution and acceptance. He called it rebellion.”

On Meursault in The Stranger: “He refuses all the different figures of the father – the priest and the judge. By choosing death and blood, he tries to tries to find something equivalent to the sun.”

Robert Harrison:

“Absurdity is a weapon that you have in your heart, in your mind. Keep it present to remember always the constant of the human condition.”

“It’s very easy to be on the side of justice when nothing is at stake.”

If ever history, with its rage, death, and endless suffering, were to become everything, human beings would succumb to madness. History is reality.”

“For Sartre, there is nothing redemptive in the sun and sea. We must keep our eyes fixed on the Medusa head of reality.”

“The difference between a northern and southern sensibility is the difference between acceptance of life and an assault on life.”

Albert Camus:

“Even my revolts were brilliant with sunshine.”

“I was poised midway between poverty and sunshine. Poverty prevented me from judging that all was well in the world and in history, the sun taught me that history is not everything.”

“Poverty, first of all, was never a misfortune for me; it was radiant with sunlight. I owe it to my family, first of all, who lacked everything and who envied practically nothing.”

“The sun that reigned over my childhood freed me from all resentment.”

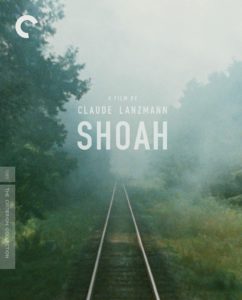

Shoah is an austere, anti-spectacular film, without archival footage, newsreels or a single corpse. Lanzmann ‘showed nothing at all’, Godard complained. That was because there was nothing to show: the Nazis had gone to great lengths to conceal the extermination; for all their scrupulous record-keeping, they left behind no photographs of death in the gas chambers of Birkenau or the gas trucks in Chelmno. They hid the evidence of the extermination even as it was taking place, weaving pine tree branches into the barbed wire of the camps as camouflage, using geese to drown out cries, and burning the bodies of those who’d been asphyxiated. As Filip Müller – a member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, the Special Unit of Jews who disposed of the bodies – explains in Shoah, Jews were forced to refer to corpses as Figuren (‘puppets’) or Schmattes (‘rags’), and beaten if they didn’t. Other filmmakers had compensated for the absence of images by showing newsreels of Nazi rallies, or photographs of corpses piled up in liberated concentration camps. Lanzmann chose instead to base his film on the testimony of survivors, perpetrators and bystanders. Their words – often heard over slow, spectral tracking shots of trains and forests in the killing fields of Poland – provided a gruelling account of the ‘life’ of the death camps: the cold, the brutality of the guards, the panic that gripped people as they were herded into the gas chambers.

Shoah is an austere, anti-spectacular film, without archival footage, newsreels or a single corpse. Lanzmann ‘showed nothing at all’, Godard complained. That was because there was nothing to show: the Nazis had gone to great lengths to conceal the extermination; for all their scrupulous record-keeping, they left behind no photographs of death in the gas chambers of Birkenau or the gas trucks in Chelmno. They hid the evidence of the extermination even as it was taking place, weaving pine tree branches into the barbed wire of the camps as camouflage, using geese to drown out cries, and burning the bodies of those who’d been asphyxiated. As Filip Müller – a member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, the Special Unit of Jews who disposed of the bodies – explains in Shoah, Jews were forced to refer to corpses as Figuren (‘puppets’) or Schmattes (‘rags’), and beaten if they didn’t. Other filmmakers had compensated for the absence of images by showing newsreels of Nazi rallies, or photographs of corpses piled up in liberated concentration camps. Lanzmann chose instead to base his film on the testimony of survivors, perpetrators and bystanders. Their words – often heard over slow, spectral tracking shots of trains and forests in the killing fields of Poland – provided a gruelling account of the ‘life’ of the death camps: the cold, the brutality of the guards, the panic that gripped people as they were herded into the gas chambers.

I owe the Stanford University Libraries five books by Saturday, and naturally one of them is AWOL. The other four are stacked up neatly by the door, ready for return. Where did the fifth go? Meanwhile, in my search I stumbled across Dikran Karagueuzian‘s Conversations with

I owe the Stanford University Libraries five books by Saturday, and naturally one of them is AWOL. The other four are stacked up neatly by the door, ready for return. Where did the fifth go? Meanwhile, in my search I stumbled across Dikran Karagueuzian‘s Conversations with

With the publication of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus in the same year, Camus became a public figure and an existential legend, though he eschewed the link with

With the publication of The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus in the same year, Camus became a public figure and an existential legend, though he eschewed the link with