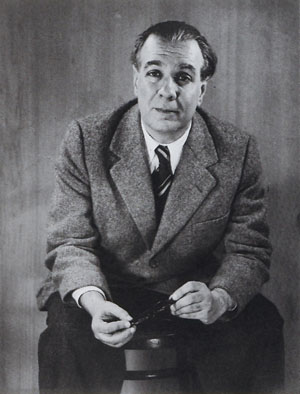

Remembering poet Robert Mezey (1935-2020): “brilliant, mercurial and often rebellious” – with a “great tragedy,” too.

Saturday, May 2nd, 2020The poet Robert Mezey is dead. According to his daughter Naomi Mezey, the former Stanford Wallace Stegner fellow died on April 25 of pneumonia in Maryland. The award-winning poet, anthologist, and Pomona College professor was 85. “Brilliant, mercurial and often rebellious, Mezey came to artistic maturity in the 1960s. His footloose early career embodied the challenges and changes of that dramatic period in American letters,” former California poet laureate Dana Gioia writes in the Los Angeles Times. The obituary offers an excellent and punchy summary of his rather unconventional life. Read it here.

Mezey entered Kenyon College at 16, where he studied with poet-critic John Crowe Ransom, but dropped out after two years. He was in the U.S. Army, but discharged as a “subversive.”

From the L.A. Times: “Encouraged by poet Donald Justice, who became a lifelong friend, Mezey began graduate studies at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Once again, he dropped out — but for a happier reason. His first book, “The Lovemaker” (1960) had won the Lamont Poetry Prize.

“On the basis of that debut volume, Mezey received the Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, but the start of the fall semester found him in Mexico rather than Palo Alto. His new mentor, the rigorously formalist poet Yvor Winters, had to send him money to travel back to the U.S. Their relationship soon soured,” Dana wrote.

Poet and Stanford Professor Ken Fields recalled in an email: “”He and Winters did not like each other, though Bob may have changed later in a delightful clerihew on him.” He knew him later in his career, through his friends Don Justice and Henri Coulette. “Bob eulogized Henri (Hank) and my first teacher, Edgar Bowers.”

From the Los Angeles Times:

Although he still lacked a graduate degree — a situation that would not change until Kenyon awarded him an honorary doctorate in 2009 — Mezey taught briefly at several universities. His departures were sometimes abrupt.

At Franklin and Marshall College in Pennsylvania, Mezey urged his students to burn their draft cards. Offered his full year’s salary, he made an early exit.

Meanwhile Mezey’s poetic style changed; he followed the zeitgeist into free verse. “When I was quite young,” he wrote, “I came under unhealthy influences — Yvor Winters, for example, and America, and my mother, though not in that order.”

He eventually returned to metrical forms and translation towards the century’s end.

“Anyone searching out his Collected Poems 1952-1999 ought to be impressed by the breadth and depth of a modern poet they probably have never heard of, wrote Ken. “‘Terezín’ is a great and moving poem on a watercolor by thirteen-year old Nely Sílvinová in a German concentration camp for children headed for Auschwitz. Among many others, I think of ‘To a Friend on the Day of Atonement’ (the phrase, ‘Jewless in Gaza’) and ‘The Wandering Jew.'”

“He could also be funny and small, as in his praise of minor poets, among whom, I think, he would include himself.” Then Ken cited this one:

To My Friends in the Art

Flyweight champions, may you live

The proverbial thousand years

To whatever smiles and cheers

Flyweight audiences may give.

Ounce for ounce as good as any,

Modest few among the many,

Swift, precise, diminutive,

Flyweight champions, may you live.

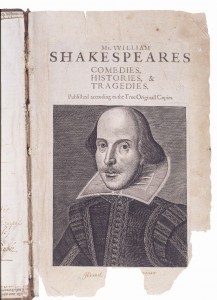

Dana Gioia describes “his greatest tragedy” as the unpublished Borges translations, but this misfortune that still can be amended (we hope):

Meanwhile Mezey had been drawn to poetic translation. His Selected Translations (1981) contained compelling versions of Spanish, French, and Yiddish authors. His greatest undertaking, however, was to prove a disaster.

With his Pomona College colleague Dick Barnes, Mezey undertook a translation of the poems of Jorge Luis Borges. After some initial encouragement from the Argentinean author’s widow, the two poets spent years crafting suave translations that replicated Borges’s original metrical forms.

Then the pair discovered they could not obtain the English-language rights. Mezey’s finest translations remained unpublished except in a few copy-shop collations circulated among friends.

Ken says he has a copy of the “wonderful” translations somewhere; let’s hope others do, too. “We do have the great ‘A Rose and Milton,’ and a couple of others. Somewhere I have the manuscript.”

Dana notes that Mezey was a religious skeptic, who did not believe in the afterlife. “Instead he offered a gentle vision of death”:

Blessed oblivion, infinitely forgiving,

Perpetual peace and silence and complete

Absence of pain. Now that’s what I call living.

Ken Fields remembered another Mezey anecdote (I expect there are many floating in the world at large): “A few years before my time, Mezey was awarded a Stegner Fellowship. … In those days the fellows got all the money at once, and Bob absconded with the stipend. Phil Levine, his friend at the time, said he had no problem with Bob taking the money, but he also took the Levine’s babysitter, and that was a serious offense. When the Collected Poems came out, Bob sent me a copy, with the understanding that I would send him twenty dollars. I neglected to do it, not deliberately, and it stayed on my mind on and off for years. Time to call it even.”