“I dreamt we were occupied by Nazis, and that those Nazis were us.”

Saturday, March 19th, 2022Maria Stepanova, one of Russia’s most recognized and honored figures – as poet, novelist, journalist, essayist, and publisher – has penned a knockout essay (translated by the excellent Sasha Dugdale) over at The Financial Times. A few excerpts :

I can’t stop looking at photographs taken in Ukraine during these unending days of war, a war so unthinkable that it’s still hard to believe in the reality of what is happening. The streets of Kharkiv — rubble, concrete beams, black holes where windows should be, the outlines of beautiful buildings with their insides burnt away. A station, a crowd of refugees trying to board a departing train. A woman carrying a dog, rushing to get to a shelter in Kyiv before the shelling begins. Bombed houses in Sumy. A maternity hospital in Mariupol after a raid — this I will not describe.

An 80-year-old friend told me of a dream she’d once had: a huge field filled with people lying in rows of iron beds. Rows and rows of people. And rising from this field, the sound of moaning. I always knew, she said, that this was to be expected. It would come to pass. Dreams about catastrophe are common in what was once called the “post-Soviet world”; other names will surely appear soon. And in these recent days and nights, the dreams have become reality, a reality more fearful than we ever thought possible, made of aggression and violence, an evil that speaks in the Russian language. As someone wrote on a social media site: “I dreamt we were occupied by Nazis, and that those Nazis were us.”

The word “Nazi” is one of the most frequently used in the political language of the Russian state. Speeches by Vladimir Putin and propaganda headlines often use the word to describe an enemy that they say has infiltrated Ukraine. This enemy is so strong that it can and must be resisted with military aggression: the bombing of residential areas, the destruction of the flesh of towns and villages, the living tissue of human fates.

The word still horrifies us, and in our world there are certainly candidates for its application. But propagandists use the word like the black spot in Treasure Island, sticking it wherever it suits them. If you call your opponent a Nazi, that explains and justifies all and any means.

***************

Right now a decision is being made about the sort of world we will live in and, in some ways, have already been sucked into: we exist and act in the black hole of another’s consciousness. It calls up archaic ideas of nationhood: that there are worse nations, better ones, nations that are higher or lower on some incomprehensible scale of greatness; that all Ukrainians (or Jews, Russians, Americans and so on) are weak, greedy, servile, hostile — and these cardboard cut-outs are already promenading through the collective imagination, just as they were before the second world war. As they say in Russia, “the dead take hold of the living”, and here these dead are ideas and concepts into which new blood flows and they begin killing, just as in a horror film.

***************

Resisting today means freeing ourselves from the dictatorship of another’s imagination, from a picture of the world that grasps us from inside and takes hold of our dreams, our days, our timelines, whether we want it or not. A battle for survival is going on right now in Ukraine; a battle for the independence of one’s own rational mind. It is going on in every house and in every head. Here as well as there, we must resist.

Read the whole thing over at The Financial Times. It’s brave; it’s stunning; it’s urgent.

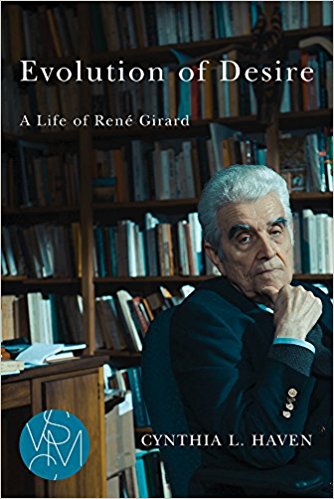

«Линчевание узнается по запаху», — сказал как-то Жирар, походя упомянув в разговоре роман Фолкнера. Эту непривычно жесткую фразу он произнес с несвойственным ему отвращением. Что имелось в виду, не уточнил, но друзья рассказали, что 1952—1953 годы, которые он провел на сегрегированном американском Юге, были для него сущей мукой. Кое-кто полагает, что именно там родилась его идея «козла отпущения», но это явная натяжка, к тому же недооценивающая его гениальную интуицию, которая сплетается со множеством наблюдений и научных находок в мощную теорию, описывающую положение человека и дающую ключ к нашему прошлому, настоящему и будущему. Эти идеи Жирар окончательно сформулировал уже после того, как книга «Обман, желание, роман» заявила о себе в литературном мире. «Я прожил год в Северной Каролине. — вспоминал он позднее. — Это было не худший штат на Юге, но полностью сегрегированный и довольно консервативный». Говорил об этом Жирар без сожаления: его завораживало буйство зелени, однако можно предположить, что роскошная краса этих мест только усиливала когнитивный диссонанс.

«Линчевание узнается по запаху», — сказал как-то Жирар, походя упомянув в разговоре роман Фолкнера. Эту непривычно жесткую фразу он произнес с несвойственным ему отвращением. Что имелось в виду, не уточнил, но друзья рассказали, что 1952—1953 годы, которые он провел на сегрегированном американском Юге, были для него сущей мукой. Кое-кто полагает, что именно там родилась его идея «козла отпущения», но это явная натяжка, к тому же недооценивающая его гениальную интуицию, которая сплетается со множеством наблюдений и научных находок в мощную теорию, описывающую положение человека и дающую ключ к нашему прошлому, настоящему и будущему. Эти идеи Жирар окончательно сформулировал уже после того, как книга «Обман, желание, роман» заявила о себе в литературном мире. «Я прожил год в Северной Каролине. — вспоминал он позднее. — Это было не худший штат на Юге, но полностью сегрегированный и довольно консервативный». Говорил об этом Жирар без сожаления: его завораживало буйство зелени, однако можно предположить, что роскошная краса этих мест только усиливала когнитивный диссонанс.