“A Company of Authors” is back! An exciting afternoon of lively authors, fascinating books, and “Evolution of Desire”!

Monday, April 16th, 2018

See the second name from the top on the poster above? That’s Humble Moi. You can call me “Moi” for short. And I am personally inviting you to come to “A Company of Authors,” Prof. Peter Stansky‘s celebration of recent books by Stanford authors at the Stanford Humanities Center – this Saturday, April 21, from 1 to 5:15 p.m. (I know, I know… the poster above says 5 p.m. Keep reading…)

Patrick Hunt at the Stanford Bookstore.

Like the Another Look book club, it’s Stanford’s gift to the community. It’s free, and all members of the community are welcome. I’ve written about previous years here and here and here and here. Usually, I moderate the panel for poets; a few years ago, I gave a pitch for Another Look instead (my comments here), and seven years ago I presented my book, An Invisible Rope: Portraits of Czesław Miłosz. This year, I will be attending as an author, discussing my brand-new Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard.

Here’s the thing: you can drop by to hear the twenty-one authors discuss their event (schedule of speakers below or here) at any time during the afternoon, and leave when you wish. Some people stay the whole afternoon. Some people come late. Some people come at the beginning and leave early. Please don’t do that! Gaze at the schedule below. I am the very last speaker. Please, please stay to the very end! Wait and talk to me afterwards! I want to meet you! I want to sign your books! (Oh, and the Stanford Bookstore attends, too, selling all the books at a discount. We want you to buy lots.)

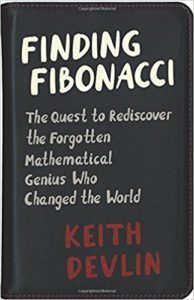

Moreover, the last panel has a terrific team, presenting some memorable characters: Stanford archaeologist Patrick Hunt presenting his new book, Hannibal. And Stanford mathematician Keith Devlin discussing thirteenth-century Leonardo da Pisa, the subject of his Finding Fibonacci: The Quest to Rediscover the Forgotten Mathematical Genius Who Changed the World . And I will discuss on a very modern hero, Stanford’s René Girard, the French theorist who wrote about human imitation, envy, violence, and scapegoating.

Moreover, the last panel has a terrific team, presenting some memorable characters: Stanford archaeologist Patrick Hunt presenting his new book, Hannibal. And Stanford mathematician Keith Devlin discussing thirteenth-century Leonardo da Pisa, the subject of his Finding Fibonacci: The Quest to Rediscover the Forgotten Mathematical Genius Who Changed the World . And I will discuss on a very modern hero, Stanford’s René Girard, the French theorist who wrote about human imitation, envy, violence, and scapegoating.

Peter Stansky, author of many volumes on modern British history, assures me that the final spot to anchor the day is a position of honor. So please come see me crowned in glory. I’ll be waiting for you. And I’ve highlighted and hyperlinked some of the other authors who have been featured in these pages on the schedule below (please note: Steve Zipperstein has had to cancel his attendance).

Marilyn Yalom signing books

Now you will ask why does the poster that was used in publicity list the event as ending at 5 p.m., yet the schedule below ends at 5:05 p.m., and elsewhere it says 5:15 p.m. That’s because we noticed that the last panel was five minutes short, and that means we’d all be talking awfully, awfully fast. So the panel ends at 5:05. But after that, we expect you’ll all want to head into the lobby, drink more tea and eat more cookies, buy more books, and many of the authors will be chatting and lingering and longing to sign your books till 5:15 or so. In fact, the hubbub and conversation in the lobby after it’s all finished is one of the funnest things of all.

Come when you can. Stay as long as you can. It’s always lively, informative, and thought-provoking.

SCHEDULE

1:00 pm Welcome (Peter Stansky)

1:05 pm – 1:35 pm The Wide Range of History

Peter Stansky, Chair

Nancy Kollmann, The Russian Empire 1450–1801

Nancy Kollmann, The Russian Empire 1450–1801

Mikael D. Wolfe, Watering the Revolution: An Environmental and Technological History of Agrarian Reform in Mexico

Thomas S. Mullaney, The Chinese Typewriter: A History

1:40 pm – 2:10 pm Killing and Controlling the Population

Paul Robinson, Chair

Carolyn Chappell Lougee, Facing the Revocation

Philippa Levine, Eugenics

2:15 pm – 2:45 pm Considering Life

Tania Granoff, Chair

Peter N. Carroll, An Elegy for Lovers

Irvin D. Yalom, Becoming Myself: A Psychiatrist’s Memoir

2:50 pm – 3:20 pm Life and Love

2:50 pm – 3:20 pm Life and Love

Edith Gelles, Chair

Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci, Contraceptive Diplomacy

Karen Offen, The Woman Question in France, 1400–1870

Marilyn Yalom, The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love

3:25 pm – 3:55 pm The Former British Empire

Kristin Mann, Chair

Jack Rakove, A Politician Thinking: The Creative Mind of James Madison

Priya Satia, Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution

Aidan Forth, Barbed-Wire Imperialism: Britain’s Empire of Camps, 1876–1903

4:00 pm – 4:30 pm The Many Worlds of Stanford

Larry Horton, Chair

4: 00 pm – 4:30 pm The Many Worlds of Stanford

00 pm – 4:30 pm The Many Worlds of Stanford

Larry Horton, Chair

Tom DeMund, Walking the Farm

Peter Stansky et al., The Stanford Senate of the Academic Council

Robin Kennedy on behalf of Donald Kennedy, A Place in the Sun: A Memoir

4:35 pm – 5:05 pm Rich Lives

Charles Junkerman, Chair

Patrick Hunt, Hannibal

Keith Devlin, Finding Fibonacci

Cynthia Haven, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard

This event is co-sponsored by Stanford Continuing Studies and the Stanford Humanities Center, with special thanks to the Stanford Bookstore.

A villanelle, for those of you who don’t know the lovely form with its remarkable incantatory power, is a 19-line poem with a rhyme-and-refrain scheme that runs as follows: A1bA2 abA1 abA2 abA1 abA2 abA1A2 where letters (“a” and “b”) indicate the two rhyme sounds, upper case indicates a refrain (“A”), and superscript numerals (1 and 2) indicate Refrain 1 and Refrain 2.

A villanelle, for those of you who don’t know the lovely form with its remarkable incantatory power, is a 19-line poem with a rhyme-and-refrain scheme that runs as follows: A1bA2 abA1 abA2 abA1 abA2 abA1A2 where letters (“a” and “b”) indicate the two rhyme sounds, upper case indicates a refrain (“A”), and superscript numerals (1 and 2) indicate Refrain 1 and Refrain 2.