The writer’s life. It’s not what you think.

Thursday, September 27th, 2012Two troubled childhoods. Two men who grew up absent the parental care all children need. One homeless child spent time living in an urban sewer system, the other boy bounced from city to city, state to state.

A recipe for lifelong failure and therapy, yes?

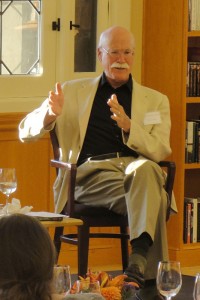

Nope. Both grew up to be award-winning writers: one is Tobias Wolff, author of Old School, This Boy’s Life and In Pharaoh’s Army, the other is Richard Rhodes, Pulitzer-awarded author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb and, more recently, the acclaimed Hedy’s Folly. The two friends spoke at a private, invitation-only only event in the Bender Room in Green Library on the evening of Sept. 17 about what it takes to become a writer. It’s not what you think.

Both talks were so good I can do no better than share my notes with you.

Richard Rhodes: “Urban Hucky Finns”

Rhodes was born in 1937, and his mother committed suicide the following year. He lived in a series of boarding houses in Kansas City, Missouri.

Could it get worse? It did.

His father remarried and his stepmother was abusive, not allowing the brothers in the house during the daytime. At some point, he and his older brother Stanley did what so many abused children do: they took to the streets of Kansas City.

Rhodes recalled “I think of us as urban Hucky Finns,” he said. Far from feeling sorry for himself, he recalled it as an adventure.

“The big city junkyard wasn’t fenced off from the world. I could wander around there and discover pieces of the world,” he said. “The vacuum tubes smelled of hot varnish. Baby strollers and tricycles and all those wheels. Pieces of automobiles.”

At one point, he took apart a sewing machine he found and put it back together again – and had two extra pieces leftover. “I felt that I had made a breakthrough.”

“It doesn’t surprise me I became interested in science and technology,” he said.

The brothers went through the dumpsters for food. A half-eaten hamburger was something to be prized: “To brush off the cigarette ash, was to have something really wonderful.”

Sewers were for the summers. He remembers tunnels that were 12 feet in diameter. “They didn’t have sewage in them, they just had water in them … and a healthy population of rats.”

The brothers would pop up for fresh air at various points in the city through the manhole covers in the street, “no doubt scaring people.” At that time – he was about 10 or 11 – he remembers reading Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. It matched his life.

“It was so wonderful … it was still the first big novel I ever read,” he said.

“By the time I got to adolescence, I was really fascinated by science fiction.” In particular, he was impressed by Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, exploring the ethics of being a robot.”

“Trivial as it sounds, it was my first encounter with philosophy and ethics.” Then Albert Schweitzer’s My Life and Thought showed him “a way to think of moral issue of world.”

In 1949, his older brother went to the police. The brothers were told that they were “obviously starved.” Stanley Rhodes was 5’ 4” and weighed 98 pounds.

The boys went to a farm – a “very empowering business,” Rhodes recalled. Then, the miracle, or as he put it, “I got lucky.” He was offered a four-year, all-expenses-paid scholarship to Yale.

Yale was not exactly like home. “I was feeling as if landing on Mars.”

Tobias Wolff – call him “Jack”

“My folks separated and quickly divorced when I about 5,” Tobias Wolff said. “My father was not good about support.” His mother worked at the Dairy Queen during the day, while she took nighttime secretarial classes.

The local library was his babysitter. “I found myself going to the library a lot.”

“I spent a lot of time in those libraries, feeling safe.” Palo Alto’s cozy College Terrace branch library is akin to the libraries he remembers.

Although he is “not at all nostalgic for world grew up with” in the 1950s, “there’s an intimacy about that world I remember fondly. It’s one of the things that stayed with me.”

He developed an addiction for the novels of Albert Payson Terhune, who wrote such immortal classics as The Faith of a Collie. “I read all those books, one after another.”

“He wrote about Collie dogs. That’s all he wrote about. He had no other subject,” he said. “He did his best to stay within bounds of Collie psychology,” said Toby – even to the edges of canine ESP. In one novel, “the Master joins up in the great effort of World War I.” Back home, the dog suffers, knowing his Master has fallen in Belgium. “This dog gets himself to Belgium, finds the man and pulls him to safety.”

Relief was on the way. When he was 10 or 11, one prescient librarian asked him read the works of Jack London. She pulled White Fang off the shelf for him. “Then I read everything by Jack London.”

He changed his name to Jack Wolff. “My mother agreed to let me change my name on condition I was baptized at the Church of the Madeleine.” In Salt Lake City, where they lived, he was one of two children in his school who was not Mormon. “She was terrified I would become a Mormon.” Baptism was a fair trade for a name like Jack.

“I was beginning to write imitations. To build a fire,” he said. “Books seemed to come from another planet. I really did it out of love, and for the pleasure of writing down stories that were read only by my mother for years.”

If being a “professional writer” means making a profit on one’s writing, he made it early, giving copies of stories to his friends to turn in for extra credit.

When his memoir This Boy’s Life came out, he got a call from one of his boyhood pals from Washington state, who was living in Alaska. “I hear there’s this book and I’m in it,” he said.

The pal had turned in for extra credit the far-fetched story of a family of Italian acrobats and domineering patriarch. In the finale, he dives into pool of water from great height. The family had taken out insurance on his life, drained pool, and painted it blue. The End.

“What grade did she give you?” he asked. “She gave me a ‘C’,” he replied.

“I thought it was an ‘A’ story,” Toby replied thoughtfully. Apparently, the teacher agreed. “I think it’s an ‘A’ story,” she told the budding plagiarist. “But you didn’t write that. Jack Wolff wrote that.”

His attendance at Pennsylvania’s Hill School changed his life. The school emphasized literature, and writers like Robert Frost, William Golding were treasured.

The rest of that story is told in his memoirs. He lost his scholarship for repeated failures in mathematics. He went into the army, and then to Vietnam. “Even in army kept writing. I was conscious of myself as someone who wanted to be writing.”