Long after the Cold War, have we become our opponents? Václav Havel weighs in.

Saturday, February 25th, 2017I have long observed how people become the thing they hate most, so when René Girard described how locked rivals come to resemble each other more and more, it was no surprise to me. Czech writer, dissident, and president Václav Havel apparently felt much the same way. This recent New Yorker article – Pankaj Mishra’s “Václav Havel’s Lessons on How to Create a ‘Parallel Polis” – has been an open tab in my Google Chrome window for at least a week. Don’t you wait that long to read it. Despite Mishra’s Manichaean cast of mind (it’s not a case of the pure and the monstrous, we could all use a little self-examination), it is essential reading that expresses some important thoughts for this particular historical moment:

Have we become “statistical choruses of voters”?

The problems before humankind, as Havel saw it, were far deeper than the opposition between socialism and capitalism, which were both “thoroughly ideological and often semantically confused categories [that] have long since been beside the point.” The Western system, though materially more successful, also crushed the human individual, inducing feelings of powerlessness, which—as Trump’s victory has shown—can turn politically toxic. In Havel’s analysis, politics in general had become too “machine-like” and unresponsive, degrading flesh-and-blood human beings into “statistical choruses of voters.”

According to Havel, “the sole method of politics is quantifiable success,” which meant that “good and evil” were losing “all absolute meaning.” Long before the George W. Bush Administration went to war in Iraq on a false pretext, Havel identified, in the free as well as the unfree world, “a power grounded in an omnipresent ideological fiction which can rationalize anything without ever having to brush against the truth.” In his view, “ideologies, systems, apparat, bureaucracy, artificial languages and political slogans” had amassed a uniquely maligned power in the modern world, which pressed upon individuals everywhere, depriving “humans—rulers as well as the ruled—of their conscience, of their common sense and natural speech, and thereby, of their actual humanity.”

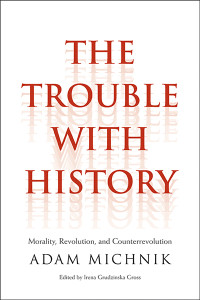

With Polish dissident editor Adam Michnik

Since Western democracies as well as Communist dictatorships had suffered a devastating loss of the human scale, it mattered little that free markets were more efficient than Communist economies. For, Havel believed, “as long as our humanity remains defenseless, we will not be saved by any technical or organizational trick designed to produce better economic functioning.” Individual freedom and social cohesion were no less under threat in the depoliticized capitalist democracies of the West. “A person who has been seduced by the consumer value system,” he wrote, and who has “no sense of responsibility for anything higher than his own personal survival, is a demoralized person. The system depends on this demoralization, deepens it, is in fact a projection of it into society.”

After he became President of his country, Havel attacked, in 1997, its “post-communist morass”: an iniquitous capitalist economy that convinced many that “it pays off to lie and to steal; that many politicians and civil servants are corruptible; that political parties—though they all declare honest intentions in lofty words—are covertly manipulated by suspicious financial groupings.” But Havel had long before noticed some manifestly deep similarities between the two rival ideologies and systems of the Cold War; they had provoked him to describe the Cold Warriors who wanted to eradicate Communism as “smashing” the mirror that reminded them of their own moral ugliness. Indeed, Havel predicted in the mid-nineteen-eighties, even as Communism began to totter, that the kind of regime described in Orwell’s “1984” was certain to appear in the West. He warned “the victors” of the Cold War that they would inevitably resemble “their defeated opponents far more than anyone today is willing to admit or able to imagine.”

Read the whole thing here.

Intellectual and cultural historian

Intellectual and cultural historian  The Maidan was the return of metaphysics. It was a precarious moment of moral clarity, an impassioned protest against rule by gangsters, against what in Russian is called proizvol: arbitrariness and tyranny. It united Russian-speakers and Ukrainian-speakers, workers and intellectuals, Ukrainians and Jews, parents and children, left and right. The Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak … described the Maidan as akin to Noah’s Ark: it took “two of every kind.” For Yaroslav, the wonder of the Maidan was the creation of a truly civic nation, the overcoming of preoccupations with identity in favor of thinking about values. People came to the Maidan to feel like human beings, Yaroslav explained. The feeling of solidarity, he said—it cannot be described.

The Maidan was the return of metaphysics. It was a precarious moment of moral clarity, an impassioned protest against rule by gangsters, against what in Russian is called proizvol: arbitrariness and tyranny. It united Russian-speakers and Ukrainian-speakers, workers and intellectuals, Ukrainians and Jews, parents and children, left and right. The Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak … described the Maidan as akin to Noah’s Ark: it took “two of every kind.” For Yaroslav, the wonder of the Maidan was the creation of a truly civic nation, the overcoming of preoccupations with identity in favor of thinking about values. People came to the Maidan to feel like human beings, Yaroslav explained. The feeling of solidarity, he said—it cannot be described.